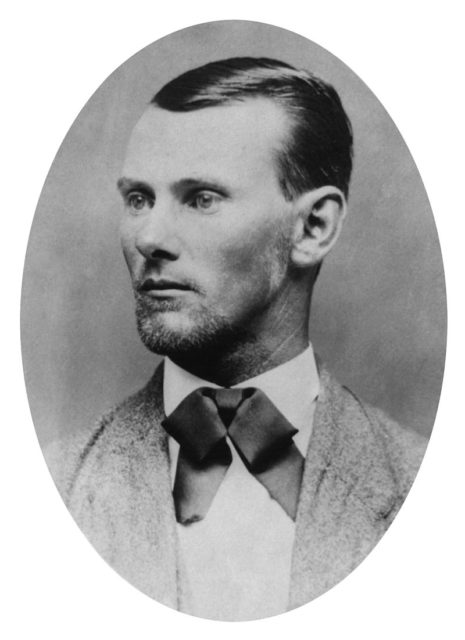

Jesse James lived only 34 years, but the legendary outlaw was both feared and cheered all over the U.S. during his own short lifetime. A letter writer, smooth talker, and cool customer, he didn’t seek fame but didn’t discourage it either, burnishing his image so people would keep talking about him—150 years after his birth. How did a bold bank robber capture the attention of a young nation in the throes of post-Civil War strife?

Jesse Woodson James was born on September 5, 1847, in Clay County, Missouri, a border state in which both Union soldiers and Confederate sympathizers lived before, during, and after the Civil War. Jesse had an older brother, Frank, his future partner in crime, and a younger sister, Susan. (Another brother died shortly after childbirth.) The James family was staunchly on the Southern side and owned as many as seven slaves on their 100-acre hemp and sheep farm. His father, Robert James, was a Baptist preacher, from whom Jesse may have inherited a silver tongue, the courage of his convictions, and the urge to strike out on his own.

In 1850, Robert left his family in Clay County to preach to miners in California gold camps, and there he shortly died, likely of cholera. His widow, Zerelda Cole James, re-married twice, first to a rich older man who disliked children and later to a doctor, Reuben Samuel, a learned man who valued education and who became a father figure to Jesse. Zerelda had four more children with Samuel, and remained a fierce supporter of her oldest two sons throughout their lives.

At the start of the Civil War, older brother Frank first joined a pro-Secessionist unit and then a band of Confederate guerrillas, or bushwhackers, led by William Quantrill and known as Quantrill’s Raiders, who attacked the Union Army in the James’s embattled home state of Missouri. In May of 1893, Union soldiers looking for Frank and Quantrill’s Raiders arrived at the James farm. They questioned and beat Jesse, then 15, and hanged his stepfather, who remarkably survived. This experience is said to have driven home Jesse’s bitter hatred of the Union and his refusal to abide post-war legislation.

At age 16, Jesse himself joined his brother in another band of marauding bushwhackers, this one led by William “Bloody Bill” Anderson, and took part in a brutal train robbery and a subsequent massacre of Union soldiers in Centralia, Missouri, that left more than 120 federal troops murdered and mutilated. Historians say Jesse was a “cool and deadly customer, unbothered by the killings.” Just a month later, in apparent retribution, Union soldiers tracked down and killed Bloody Bill, and eight months after that, killed Quantrill in May 1865. Even though he was bitter about the death of his mentors, Jesse attempted to surrender, riding into Lexington, Missouri, carrying a white flag, but was shot in the chest by a Union soldier. He crawled away and made it to his uncle’s house in nearby Harlem, where his first cousin Zerelda “Zee” Mimms tended to his wounds—and apparently his heart. Nine years later, the two would wed.

Frank and Jesse returned to Clay County after the war, but they had been changed forever. Like many former soldiers, they were too jittery from their battle experiences to settle down to a quiet farm life. Instead they turned to a life of crime.

Jesse James himself may not have participated in the first daylight bank robbery in the U.S., as he was likely still recovering from his chest wound. But historians speculate he was the mastermind behind the planning. On February 13, 1866, as many as 14 men rode their horses up the streets of Liberty, Missouri, to the red brick Clay County Savings Bank at the corner of Franklin and Water Streets (today the site of the Jesse James Bank Museum). One of the outlaws asked for change for a $100 bill, and then demanded money from the terrified teller. Outside, as the criminals beat a retreat, someone sounded an alarm, and one of the gang members shot a young man in the heart. James was reportedly unhappy about the killing. While the gang got away with around $60,000 in currency, gold, and coins, it wasn’t that much once split among them, which spurred them to rob again. Thus began a life of robbing banks, stagecoaches, and trains, often in full public view, as if taunting authorities, and with little remorse.

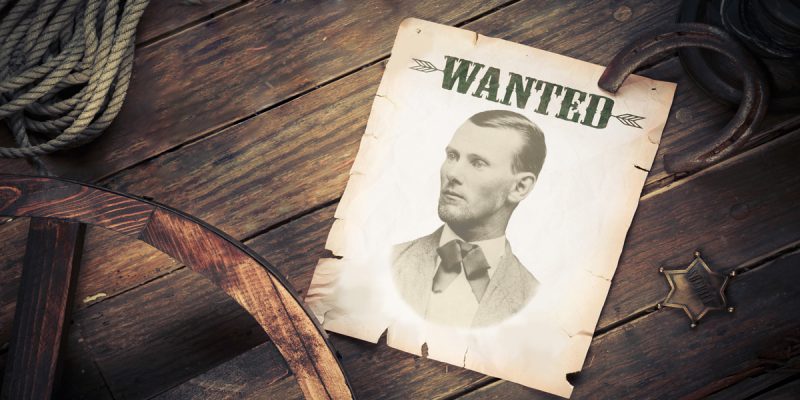

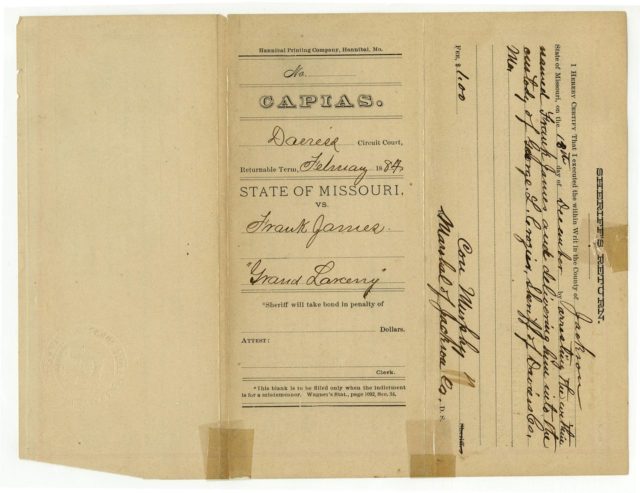

It was a bank robbery a few years later in Gallatin, in 1869, that brought Jesse James national notoriety. There he shot and killed the bank’s cashier, mistakenly thinking the man was the former soldier who had killed Bloody Bill Anderson. The murder led the state governor to offer a reward for his capture. One local newspaper editor saw in James a rebellious pro-Confederate anti-hero and encouraged James to write letters defending his actions. The editor published stories saying James rarely stole from civilians, which helped create the myth of James as a folk hero. In fact, historians say, James and his associates kept the stolen money for themselves.

By 1874, frustrated railmen called in the Pinkerton Agency to track down Jesse and Frank and their gang, which by then included Cole Younger and his brothers and was known as the James-Younger gang. The Pinkertons didn’t have luck: Pro-Confederate territory harbored the fugitives. Two Pinkerton agents wound up dead. The Pinkertons raided the James homestead, killing their young half-brother and maiming their mother, Zerelda, which outraged the local community and solidified their support of the outlaws.

A failed attempt to rob the First National Bank of Northfield, Minnesota, on September 7, 1876, was the beginning of the end for the James-Younger gang. When the cashier refused to open the bank safe, Jesse James shot him. On the street outside the bank, a shootout began between enraged local citizens and the gang, wounding the Youngers, who managed to escape but who were shortly thereafter captured. The James brothers retreated to their Missouri homestead, but later had to move to Tennessee to evade authorities. They continued to hold up trains, but they no longer had a gang of trusted accomplices. The governor of Missouri, frustrated by the elusive criminals, turned to rail barons to secure an attractive bounty of $5,000 for the apprehension of Jesse James.

Back in his home state, Jesse James recruited two men, Robert and Charley Ford, to plot a new heist. Unbeknownst to him, Bob Ford colluded with authorities. On April 3, 1882, the men met at the James residence, and when Jesse turned his back, Bob Ford shot him in the back of the head.

The legendary Jesse James was dead. It was hard for the public to believe. Hundreds flocked to the house to see for themselves. The Fords were convicted of murder, but pardoned. Two years later, Charley Ford committed suicide; Bob was shot down in a saloon in 1894. The disbelief stretched well into the next century, and in 1995, the outlaw’s remains were exhumed and DNA tested. Researchers concluded they were his remains. His grave, and that of his wife, lies at Mount Olivet Cemetery, in Kearney, Missouri.