With exceptional energy on stage and a unique voice, Ella Fitzgerald enchanted audiences all around the U.S. and beyond for six decades. She also had an excellent ability to imitate sounds from different instruments, something that was recognized to be one of her signature performance techniques, and that eventually helped popularize scat singing.

Fitzgerald would say goodbye to her audience in 1993, when she delivered the last of her public shows, and by then, it was more than clear that she had rightfully claimed her titles both as the Queen of Jazz and the First Lady of Song. She is further remembered as the first African-American female performer to collect a Grammy Award.

However, none of these lifetime accomplishments were won with ease, especially when bearing in mind that Fitzgerald was still a woman of color in times when segregation was a fact all over the country, and particularly in the Jim Crow states. Fortunately, she had people to back her up and help in critical moments of her career, particularly during the 1950s.

One of them was Norman Granz, her then manager, now widely remembered for his stances against racism and his vow to integrate all audiences. As a civil rights advocate, Granz always stood up for Ella, as he also did for the rest of the musicians with whom he worked. He would fight for their equal treatment, whether it meant his musicians needing a stay in a decent hotel or delivering a show free of difficulties caused by prejudice.

But despite the efforts of Granz, the obstacles seemed to be serious, specifically for African-American performers who were on the rise, as was the case with Ella Fitzgerald. It didn’t matter how famous she was becoming, more often than not she was limited to which venues she could perform in, of which, even in those place, African-American performers were asked to enter the venue through the back door.

Still, there was one other person that Lady Ella knew was totally supportive of her and who also happened to be one of her biggest fans. Looking back, what she did seems to be of utmost importance for the career and life of our Queen of Jazz. Which brings us back to Mocambo, the most popular jazz club in Hollywood during the 1950s. That was the same venue where Frank Sinatra made his L.A. debut and the place where figures such as Clark Gable, Charlie Chaplin, Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, and Lana Turner were keen to spend a night out.

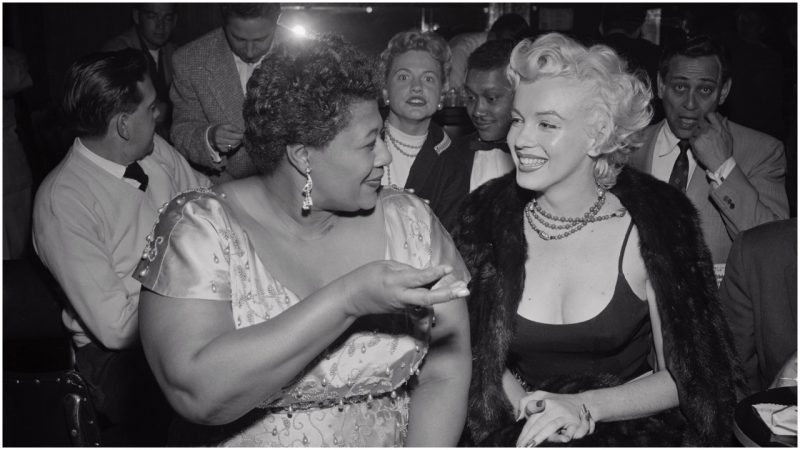

Because of her race, Ella Fitzgerald was not allowed to deliver a performance at Mocambo. At least not until her big fan, then a superstar at her peak, Marilyn Monroe, decided to pick up the phone, call Mocambo’s manager. and fix the issue. Reportedly, Monroe respected Fitzgerald so much that, in the years preceding the “Mocambo call,” she had even scrutinized Ella’s early recordings to help develop her own voice.

After Monroe helped arrange Fitzgerald’s debut at Mocambo, the fortunes of the Queen of Jazz largely changed, or as Fitzgerald herself comments years later for an August 1972 issue of the MS magazine, “I owe Marilyn Monroe a real debt… she personally called the owner of the Mocambo and told him she wanted me booked immediately, and if he would do it, she would take a front table every night. She told him — and it was true, due to Marilyn’s superstar status — that the press would go wild.”

She continues, “The owner said yes, and Marilyn was there, front table, every night. The press went overboard. After that, I never had to play a small jazz club again. She was an unusual woman — a little ahead of her times. And she didn’t know it.”

This significant episode of music and culture history, when Fitzgerald took her first steps on the Mocambo stage, unfolded on March 15, 1955. The entire episode is further dramatized in a play authored by Bonnie Greer in 2005. Monroe had helped Ella set her career to stardom.