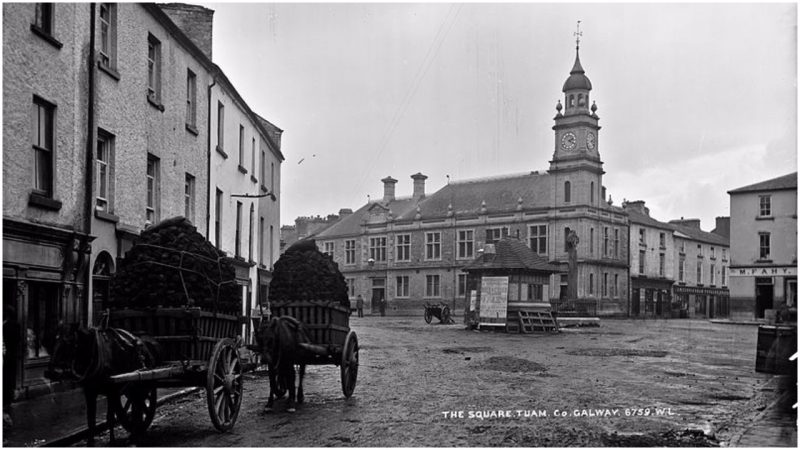

There is a burden that weighs on Ireland, a tragedy of 796 babies and toddlers buried in the backyard of Bon Secours Mother and Baby Home in Tuam, County Galway. The maternity home for unmarried mothers and their children operated from 1925 and 1961.

Excavations carried out by a Commission of Investigation revealed that a “significant” number of human remains were found at the home. Although questions about the activities of the Sisters of Bon Secours were raised beginning in the late 20th century, no investigation took place until 2016-2017. “The children of Tuam” is not an expression that people in Ireland take casually.

During the time that the home operated in Ireland, it was considered disgraceful for women to get pregnant outside of marriage, and unless they found a husband, these women didn’t stand any chance in society. Hence, the Catholic Church opened dozens of maternity homes for unmarried women and their children. Bon Secour was one of those institutions where mothers were separated from their children and had to remain elsewhere in the home, while nuns took care of the babies.

Almost 15 years after Bon Secour closed down, two boys who were playing at the site of the former Mother and Baby Home found a concrete slab. Underneath it they discovered children’s skeletons. As the boys told it, the hole was “filled to the brim.” And while the government failed to investigate the case immediately, Catherine Corless, a grandmother, gardener, and amateur historian from Taum, couldn’t rest until she discovered the truth.

Catherine Corless brought the whole case to light in 2012. She remembered how some of these children had attended the same school in Taum she did, but that they existed like ghosts. As she recalls in an interview “They were segregated from the rest of us…We weren’t allowed to play with them. These were like another species.” After years of being upset about the bones found behind the walls, Corless acquired a random sample from the government of 200 children’s death certificates at Bon Secour. She was devastated to find out that there were only two children from the home buried in the Taum graveyard. The rest did not receive a proper burial.

Katherine found out that according to the maps of the home, the place where the bones were found was the septic tank, which was allegedly used as a common burial ground. The causes of death ranged from influenza to tuberculosis.

After Corless’ article about her findings on Tuam’s maternity hospital was published in the local paper, she started receiving many calls from children who had survived the home and were interested in the truth. Many of them publicly told their stories, and they weren’t pleasant ones. The children were never given the chance of a happy childhood.

As for the dead children, the ones in the septic tank, an investigation conducted for five months between November 2016 and February 2017 showed that there were almost 800 bodies there, from 35 weeks old to three years. In her essay, Corless provocatively asks the question: “Had Catholic nuns, working in service of the state, buried the bodies of hundreds of children in the septic system?” It was also revealed that back in the 1950s the nuns received up to 1 pound for every mother and child received.

Tragically, it wasn’t confined to this home. Illegitimate children born in these homes were four times more likely to die than other babies. The reasons? There were many: lack of funding, untrained staff, inadequate care, and finally lack of love and warmth. The worst part? Members of the church and certain officials must have known what was happening.

Thanks to Katherine Corless, all this came to public attention in the media, and many children who were raised in homes such as Bon Secour got the chance to tell their stories.

Related story from us: Baby farmer Amelia Dyer was a serial killer who killed infants

There has been some criticism of the stories about Bon Secours, questioning whether the corpses were actually much older, dating from the Great Famine of the 19th century or the decades following, when infant mortality was high throughout Ireland.