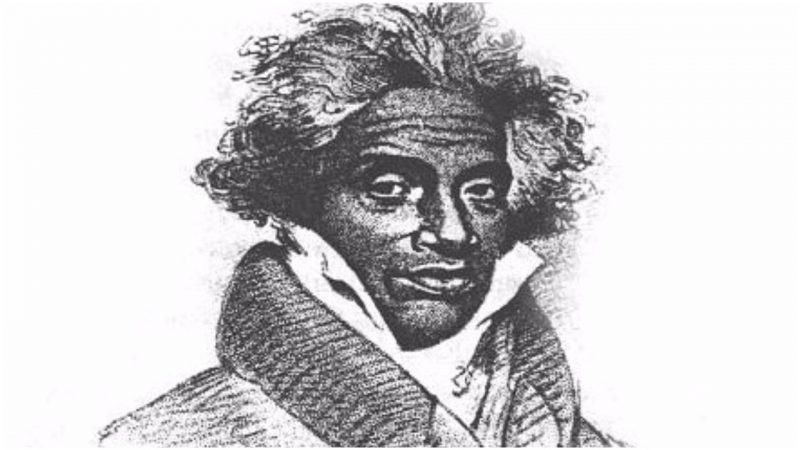

It is true to say that Abdul Rahman Ibrahim was an unfortunate Muslim prince, a man whose destiny was to spend almost his entire adult life not reigning over a kingdom but working the cotton fields in the Mississippi Delta. In the fields, he met his wife, Isabella, and they created a family of nine children.

He would commence his homecoming trip to Africa during the summer months of 1829, following four decades of enslavement in the Mississippi Delta. After years of struggles, Ibrahim had finally reclaimed his freedom helped by President John Quincy Adams. His final destination in Africa was set to be the village where he was born, in Timbo, nowadays known as the Republic of Guinea.

Tragically, he lost his life a short while after the end of his homecoming voyage due to contracting a “coastal fever.” He died on July 6, 1829, in Moravia, Liberia, which was at that time an American colony and not too far from Ibrahim’s home.

He was born to King Sori who ruled in the Fouta Djallon region, further known as the Land of the Fulbe and Jalunke. He was serving in the military when one day he was ambushed and forced onto the slave market at the age of 26.

Ibrahim’s story relates to tensions that were ongoing between the Fulbe and the Jalunke people who both inhabited the region. They were two distinct groups with different religious beliefs. The Fulbe were Muslim orientated, and the Jalunke were non-Muslim.

Georgetown gave the descendants of 272 slaves preferential admission rights

By the time Ibrahim grew up, as Professor Terry Alford explains in his book, Prince Among Slaves, the tensions between these two groups had escalated to the point of total war, following a ban on public prayer activities issued by the Jalunke officials.

When Ibrahim was captured, he was serving as a leader of one of the Fulbe army’s troops. He was quickly auctioned on the slave market and around the year 1788, he ended up on a Mississippi plantation in Natchez, in the ownership of Colonel Thomas Foster.

What may have helped Ibrahim at least a little was that he possessed the green thumb as much as good leadership skills. Thus Foster made him one of the majors on the cotton plantations. His spouse, Isabella, was also a slave on the estate, and they married around 1794, and of their nine children, five were boys and four were girls.

But settling down with a family on a cotton plantation run by slaves, while also being one, was certainly not anyone’s dream. Ibrahim made a few attempts to reclaim freedom and leave, but things did not go that smoothly. The first spark of hope had come following a visit from Dr. John Cox, an Irish surgeon who saw a familiar face in the slave.

As sources tell, Ibrahim and Cox already knew each other because Cox had previously traveled to Ibrahim’s homeland, and in one instance had fallen sick for almost half a year. It was Ibrahim’s family who took care of him while he was ill, and now it was time to return the favor.

Initially, Cox offered to become Ibrahim’s new owner, to “buy” him from Foster, only to later grant him his freedom, but Foster refused the offer. Cox supposedly tried anything that he could think of — lobbying among high officials, to create pressure for Ibrahim’s release–but no matter how much he tried, Ibrahim remained enslaved. Cox died around 1816.

Ten years later, it happened that Ibrahim wrote a letter in Arabic and had it sent to his relatives in West Africa. Allegedly, the man who picked up the letter from Natchez, named Andrew Marshchalk, had forwarded a copy of it to Senator Thomas Reed. The officials in Washington, D.C., thinking that Ibrahim originated from Morocco, then forwarded the letter to Morocco and it eventually ended up in the hands of the Moroccan Sultan.

Regardless of the fact that Ibrahim did not come from Morocco, the Sultan reportedly took an interest in his case and eventually set up a new petition that now addressed the President of the United States.

From here on in, fortunes changed for the forgotten African prince, and a process of fundraising was underway to help him become free of slavery. The collected funds were not enough to support the return of the entire family, but there was still enough for Ibrahim, now in his mid-60s, and his wife to board a vessel to Africa.

Sadly, his death occurred at the end of their journey, and he was never able to see his birth village again. Following his death, his spouse settled in Liberia. Tragically, only two of their children were released and traveled to Africa, while the rest remained enslaved.

Ibrahim was aged 66 when he passed away. He never became a king who could leave a kingdom behind as a legacy. What he left was only a life story that sheds light on some of the darkest moments of humanity–the terrible history of enslavement.