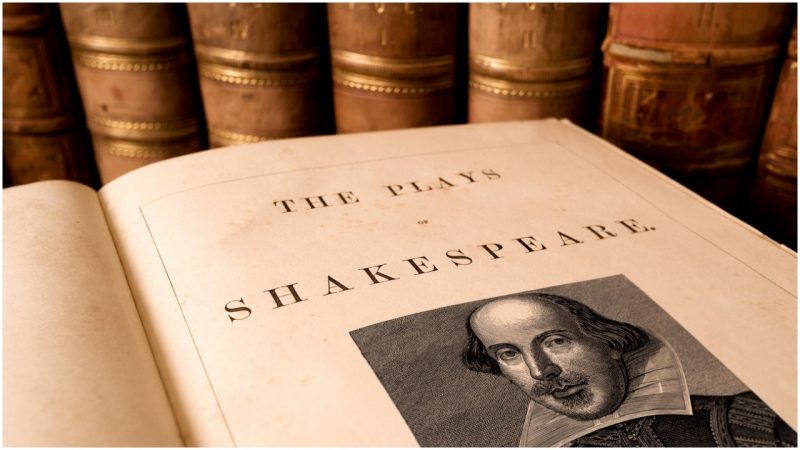

Following the death of William Shakespeare in 1616, he did not instantly become the literature giant we know today. It was a slow process that required many decades, if not centuries. It took at least seven years before the First Folio was comprised and issued, and it was one of the earliest sources of numerous works by Shakespeare for scholars to later scrutinize and study.

Neither did Shakespeare’s close friends and family presume that he would gain iconic status. They didn’t foresee that a paper bearing his handwriting, perhaps the personal letters he’d sent, could one day be worth millions of dollars.

Over the course of time, this lack of authentic handwritten material from Shakespeare has made for a compelling opportunity among various literary forgers.

One of the most notorious cases takes us to London in the 1790s and highlights the name of William Henry Ireland. He was born to Samuel Ireland, a publisher, collector, and a man interested in all things Shakespeare. William was born in 1775, which means by the time he pursued his literature crimes, he was twenty years old.

William Henry, not the most intelligent child, is thought to have done many things just to impress his father. He also aspired to become a great writer himself, though he apparently lacked the talent for it.

Samuel Ireland found his son a cushy job in a lawyer’s office. William Henry was scarcely ever monitored as he worked, which undoubtedly allowed him room to come up with the fake pieces he deliberately attributed to none other than his father’s favorite author, William Shakespeare.

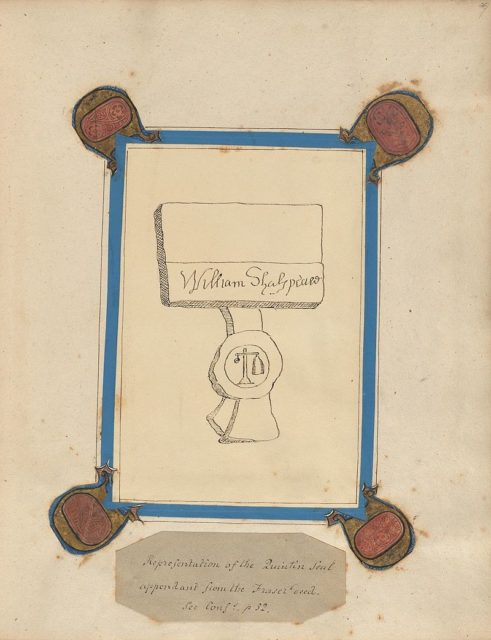

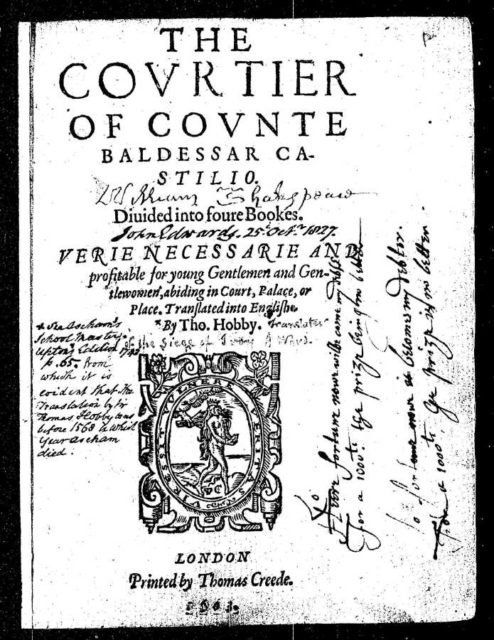

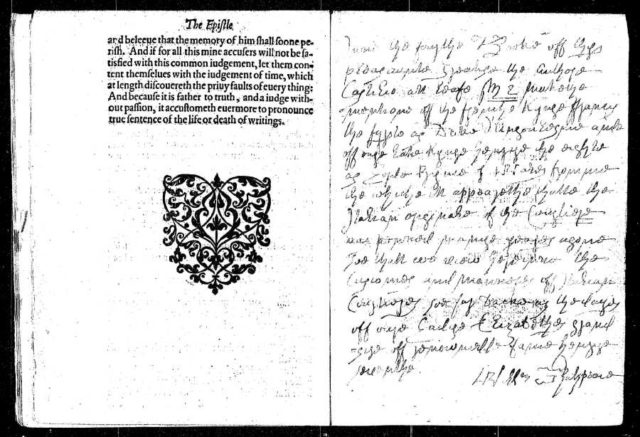

Supposedly, Ireland created his first fabrication at the end of 1794, after noticing a wavering signature of Shakespeare’s on a reproduction of an old document found in a book belonging to his father’s collection. Supposedly, he took the book into his office and began practicing Shakespeare’s signature. After not too long, he was able to copy the signature of the Bard flawlessly.

William Henry’s office was also filled with piles of very old documents of a legal nature, and parchments found among the bunch also became a treasured resource for producing fake documents and manuscripts that he attributed to Shakespeare.

He was shrewd with the material he used. To make the paper look all the more authentic, he darkened it with a flame from a candle and also made sure to add a wax seal.

Once it was done, he brought the fake piece home, explaining that he had retrieved it from a friend who had plenty more such old documents, but who had not been interested in any of them.

In his concocted story of how he had stumbled upon his findings, he reportedly also said “the friend” wanted to stay anonymous, designating him only as Mr. H. And as it turned out, “the trunk of Mr. H.” always had something new authored by Shakespeare.

A couple of experts examined the first manuscripts he brought home, and everyone indeed marveled at the “fresh findings.” To satisfy his father’s appetite for more such valuables, William Henry kept on producing more fake scripts, which he further claimed were penned by the Bard of Avon.

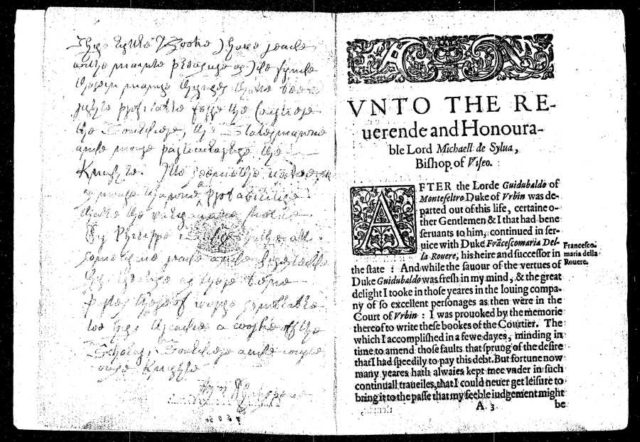

People quickly learned about the findings, some of the most prominent of which were an entire alleged first draft of King Lear as well as a fragment of Hamlet. What young Ireland did was to mimic Elizabethan writing and spelling. He transcribed the plays, deliberately adjusting them to look as if they were drafts, omitting entire pieces and adding new bits on the way.

The fake works were apparently well done, as senior Ireland kept on asking for more and more papers and manuscripts. Among the forged fakes was even a love letter from Shakespeare to his wife. It came with a piece of hair too.

Meanwhile, people kept visiting the Irelands. They continually examined the papers with the greatest curiosity but also growing suspicion, as, in those days, deliberate variants of Shakespeare’s plays were present; a good example was a version of King Lear, even staged in a theater, that concluded with a happy ending instead of a tragic one.

The entire act of forgery eventually became bigger than William Henry could have anticipated. The more famed his “findings” became, the more prone people were to believe in them. So he launched the biggest of all his forgery undertakings: producing a “previously unknown” play by the Bard. He would later remark that he had informed his father about this piece before it was even done. Or in his own words, he had “made known to Mr. Ireland the discovery of such a piece before a single line was really executed.”

Entitled Vortigern, this was a fake play that revolved around a warlord who becomes a king and falls in love with a young lady known as Rowena. William Henry first wrote the work on regular pieces of paper. As soon as he had the time to do it, as producing fake antique documents was a time-consuming process, he transcribed the play onto more authentic looking paper.

What certainly gave him away was his unimpressive writing and the confusing way he developed the plot, with many instances in the text being atypical to what Shakespeare would have written. Regardless of this fact, William Henry still managed to obtain rights to stage Vortigern at the Drury Lane Theater in London.

But by the time the premiere was set to take place, the year was 1796, and everyone was already aware of a paper authored by an expert on Shakespeare, Edmond Malone, which thoroughly explained the fabrications of the young Ireland.

Vortigern was not staged following that and, shortly after, the youngster took entire responsibility for his wrongdoings. In the beginning, Samuel Ireland couldn’t imagine that his son was smart enough to produce so many fake manuscripts. Sadly, some critics denounced Samuel Ireland himself, saying that he alone had penned the faked works, after which his reputation was completely ruined.

Following the scandal, William Henry moved to France, where he spent some 10 years. After a time, in 1832, he went about issuing the second edition of his Vortigern but without success. He passed away three years later at the age of 59.