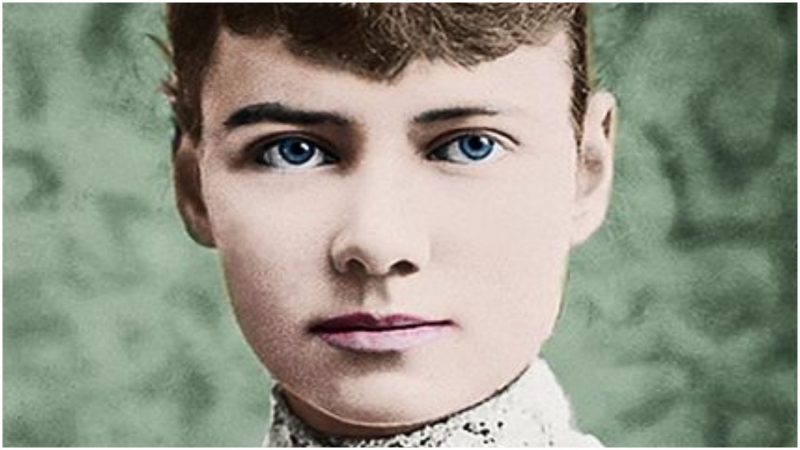

From a very young age, Nellie Bly, birth name Elizabeth Jane Cochran, aspired to become a writer, but little did she know the impact she’d have on America with her talent. It was not to be with fiction that she would find her way, but through the world of journalism.

As her life story unfolded during the late decades of the 19th century, she would, under her pen name Nellie Bly, break barriers in reporting about topics relating to women’s rights, carrying out perhaps some of the most daring investigative journalism of that time.

Born in Cohran’s Mills in Pennsylvania, Elizabeth was the daughter of a father with two occupations: running a mill and dispensing judgment as a county judge. Her mother took care of the family, which was quite a large one. Elizabeth had 12 siblings, or 14 counting the two half-siblings from her father’s previous marriage. Nicknamed “Pink,” she was the youngest of the lot.

Elizabeth lost her father at only six years of age, and his death certainly marked a turning point for the family. It was not the happiest of childhoods, to say the least, as the family fortune was quickly gone. Her mother, who remarried, went through a divorce to escape an abusive relationship. Elizabeth had to drop out of boarding school, where she planned to study to be a teacher, because she couldn’t pay the tuition.

Living with her mother Pittsburgh, now 18 years old, Elizabeth, with her facility with words, began searching for jobs in the field and was eventually hired by The Pittsburgh Dispatch after sending in a vigorous response to a story penned by Erasmus Wilson.

She had been compelled to write a response because the piece had pretty much claimed that a woman’s place was in the home, in the kitchen, doing chores and raising children. The text described women who worked as “a monstrosity.” Elizabeth’s reply to the piece must have been splendid since shortly after that, the editor-in-chief of The Pittsburgh Dispatch offered Elizabeth a position to write for $5 a week.

It was for this job that she took the pen name Nellie Bly, supposedly after Stephen Foster’s song of the same title. She carried out her first undercover mission, investigating while posing as a worker in a sweatshop and later reporting on the miserable conditions that the women had to cope with there.

Her path to stardom continued when she moved to New York, taking a post at the New York World in 1887, which later on became one of the first papers in the world to feature contents that were of a more sensationalist nature, or what one could say was the beginning of “yellow journalism.”

Among her first assignments, Nellie Bly worked on a piece concerning the experiences of the patients who stayed in mental institutions. In order to do so, she admitted herself as a patient in the notorious Blackwell’s Island hospital (today Blackwell is known as Roosevelt Island). After spending only 10 days behind the walls of the asylum, she was ready to expose the horrors of the place.

Her reporting thoroughly illustrated the experiences of the mentally ill patients, the abusive treatment they suffered, the overcrowding, and the miserable conditions. After the story was out, city officials followed it up with their own thorough investigations. The piece was actually so successful that, later that same year, Bly’s reporting on the asylum was reissued as a booklet entitled Ten Days in a Mad-House.

She notes in the introduction of the booklet, “I am happy to be able to write, as a result of my visit to the asylum and the exposures consequent thereon, that the City of New York has appointed $1,000,000 more per annum than ever before for the care of the insane.” She revealed that hundreds of people contacted her by letter concerning her visit.

Nellie also contemplated her experiences in one of the booklet’s chapters, writing, “What a difficult task, I thought, to appear before a crowd of people and convince them that I was insane. I had never been near insane persons before in my life, and had not the faintest idea of what their actions were like.”

Fearful that she might fail to deceive the doctors at the asylum that she was insane, she underwent considerable preparations, “So I flew to the mirror and examined my face. I remembered all I had read of the doings of crazy people, how first of all they have staring eyes, and so I opened mine as wide as possible and stared unblinkingly at my own reflection. I assure you the sight was not reassuring, even to myself, especially in the dead of night.”

After the publication of her juicy reporting from the asylum, it was not only that funding was raised for the institutions working with mentally ill patients, but there were also changes in policies, such as more appointments among patients and physicians, better supervision of all employees at the asylums, and regulations such as ones limiting overcrowding and assuring a more decent stay for the people who needed treatment.

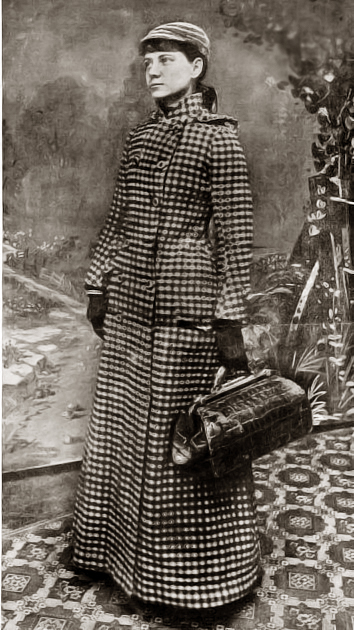

Nellie Bly would carry out more investigative work across New York, with more stories shedding light on conditions of prisons or factories. She would further fill the headlines after commencing on a trip around the world, trying to beat the fictitious record of Jules Verner’s character Phileas Fogg. Bly would circle the world, not in 80, but in less than 73 days, setting a real record and then writing about her adventures.

She would stop writing some five years after that, after marrying a wealthy businessman known as Robert Seamon who was 40 years her senior. During her time away from writing, she preferred to work with her husband, and eventually took over leadership of the business following his death.

She would finally return to journalism in 1920, back to writing stories concerning women’s issues, and particularly, at that point, on women’s right to vote. Only two years after she resumed her old career did Bly lose her life, dying from pneumonia at the age of 57, in the city of New York.