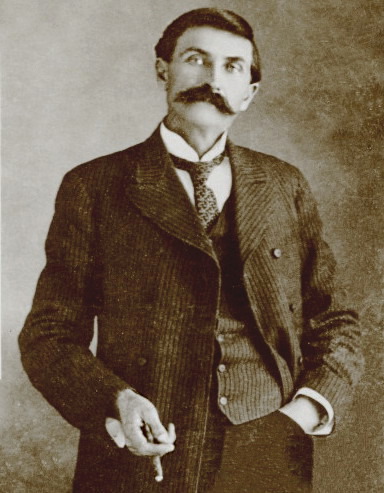

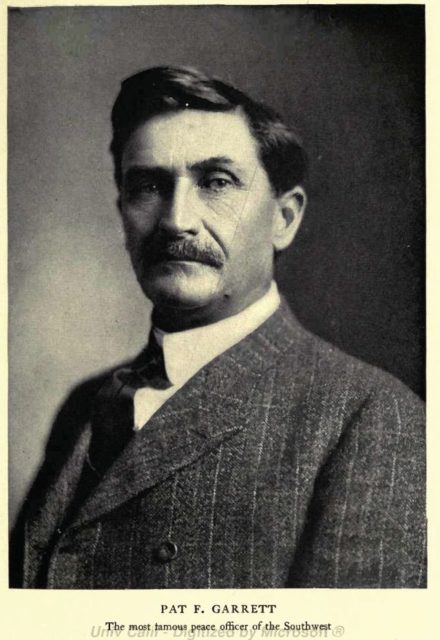

Patrick Floyd Jarvis Garrett was born in Chambers County, Alabama, on June 5, 1850. When he was a child, his father, John Lumpkin Garrett, bought a cotton plantation in Louisiana, and he grew up there with five sisters and two brothers. But his parents did not long survive the Civil War that devastated the South, leaving the children heavily in debt.

After making sure his siblings had homes with relatives, Pat headed west in 1869 and found work as a cowboy in Dallas for about six years.

By 1876 he was hunting buffalo, until a dispute with another hunter, Joe Briscoe, ended up with Garrett killing Briscoe. Garrett attempted to turn himself in to authorities, but no charges were filed. Afterward, he moved even farther west to New Mexico Territory.

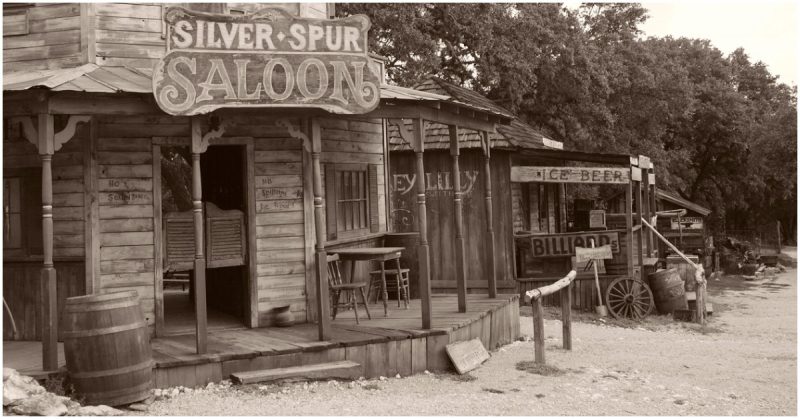

In New Mexico, Garrett worked as a cowboy for Pedro “Pete” Maxwell but quit to open a saloon. In 1879 he married Juanita Gutierrez, who died in childbirth less than a year after their marriage. A few months later, Garrett married Apolinaria Gutierrez, his sister-in-law. Together the couple had nine children – four girls and five boys.

On November 2, 1880, Garrett turned to law enforcement. He was elected to the office of sheriff of Lincoln County, New Mexico, winning ahead of incumbent Sheriff George Kimball. Garrett was so impatient to capture the outlaw William Bonney, a.k.a. “Billy the Kid,” that he asked Sheriff Kimball to appoint him deputy sheriff until his term officially began in January of 1881. He also obtained a deputy U.S. Marshal’s commission to have jurisdiction in other counties.

Garrett and his men laid siege to the Dedrick ranch at Bosque Grande on November 30th, expecting to find Billy the Kid. But they were only able to arrest John Webb, an accused murderer, along with horse thief George Davis. Garrett delivered Webb and Davis to the sheriff of San Miguel County and rode on to Puerto de Luna. While Garrett was there, he was forced to defend himself from a local bully, Mariano Leiva, by shooting him in the shoulder.

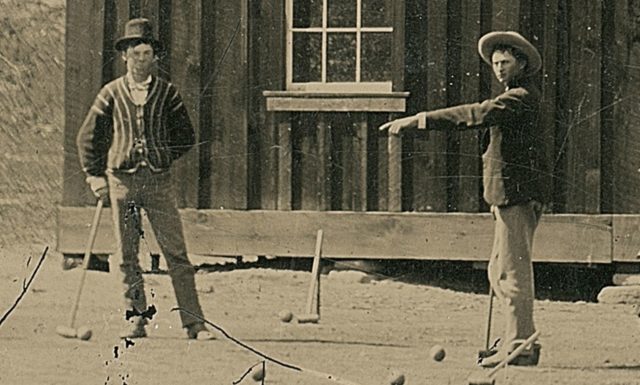

On December 19, 1880, Bonney, Billy Wilson, Charlie Bowdre, Tom Pickett, and Tom O’Folliard rode into Fort Sumner. Garrett and his men had received information that the outlaws were coming and set up an ambush. They mistook O’Folliard for Bonney, however, and fatally shot him. Bonney and the others escaped. Three days later, Garrett and his men surrounded the fugitives at Stinking Springs. One of Bonney’s men was killed; Bonney and the rest of his men were captured. On April 15th, Judge Warren Bristol sentenced Billy the Kid to hang, but he escaped before the sentence was carried out.

In July, Garrett rode to Fort Sumner and learned the Kid was staying with the same Pedro Maxwell who had employed Garrett when he first arrived in New Mexico. Garrett rode to Maxwell’s house late that night and hid in Maxwell’s kitchen. Bonney woke up and went into the kitchen, presumably to get something to eat. In the darkness, he could not see Garrett well and repeatedly asked: “Who is it?” Garrett replied with two gunshots, killing Bonney.

Following Billy the Kid’s death, the media turned him into a folk hero and made Garrett out to be the bad guy. In 1882, Garrett and his ghost writer, Marshall Upson, published The Authentic Life of Billy the Kid. Although the book was not successful when it was released, an original edition became quite valuable over the years.

Garrett did not pursue re-election for sheriff of Lincoln County in 1882. He moved to Texas, where Governor John Ireland appointed him to the Texas Rangers. But Garrett resigned before long and returned to his ranch near Roswell, New Mexico. By 1892 Garrett and his family had relocated to Uvalde, Texas, where he befriended John Nance Garner, a future United States vice-president.

In 1901 Garrett was appointed by President Theodore Roosevelt as Collector of Customs in El Paso. Amid controversy, Garrett was confirmed by the U.S. Senate on January 2, 1902. In 1903, Garrett got into a public brawl with his employee, George Gaither.

The two men were fined for disturbing the peace. President Roosevelt supported Garrett as complaints piled up and went so far as to invite him to a reunion for the Rough Riders in San Antonio in April of 1905. Garrett invited Tom Powers to go along and introduced Powers to the President as a prominent Texas cattleman; they sat for photographs with Roosevelt. Garrett’s adversaries attained copies of the photos and sent them to Roosevelt along with a note telling the President that Powers was not a cattleman, but the proprietor of a rowdy saloon. Garrett was dismissed in 1906 and returned to New Mexico.

Financially, Garrett was a failure. He was a gambler and heavy drinker and often deeply in debt. When he was unable to make mortgage payments on his ranch, the county auctioned off his personal belongings, but that raised only $650. Garrett’s friend George Curry was now the Territorial Governor of New Mexico and promised to appoint him as superintendent of the territorial prison at Santa Fe. As Curry’s inauguration was not for a few months, Garrett returned to El Paso to look for work. He moved in with an El Paso prostitute; when Curry learned of Garrett’s situation, he withdrew his offer.

Another chance at a famous crime solving came after Colonel Albert Jennings Fountain and his eight-year-old son Henry vanished at White Sands, New Mexico, in 1896. Apache scouts, the Pinkertons, and local Republican Party members all joined in to try and locate the Fountains, with no results. When Garrett was appointed Sheriff of Dona Ana County in April of 1896, it took two years for him to gather enough evidence to ask a judge in Las Cruces for warrants to arrest William McNew, Oliver M. Lee, James Gililland, and Bill Carr. McNew and Carr were the first to be arrested. On July 12, 1898, Garrett and his men encountered Oliver M. Lee and James Gililland at Wildy Well near Orogrande, Texas.

Garrett had hoped to apprehend the men while they were asleep, but Lee and Gililland set themselves up as lookouts on the roof of the bunkhouse. One of Garrett’s deputies went to check the roof and was fatally shot. Garrett settled a truce with the fugitives to retrieve his deputy, who died on the way to Las Cruces. Lee and Gililland stayed on the run for another eight months and finally surrendered. They were acquitted of the Fountain killings, and the charges for killing the deputy were dismissed.

Pat’s son Dudley arranged with Jesse Brazel for a five-year lease of the Garrett’s Bear Canyon Ranch. Brazel used the land to raise goats, which was unacceptable to the Garrets. Garrett tried to break the lease when he learned his creditor, W.W. “Bill” Cox, was financing Brazel. He and Garrett went to court, and Brazel agreed to cancel his lease with Garrett providing he could sell his 1,200 goats. Carl Adamson agreed to take the goats until Brazel discovered his estimate of the number of goats had been wrong and demanded the buyer take all 1,800 goats. Adamson agreed to meet with Garrett and Brazel to iron out an agreement.

Carl Adamson took Garrett to Las Cruces, New Mexico, and was soon joined by Brazel on horseback. At some point, someone shot and killed Garrett, but exactly who did it has been a subject of debate. Garrett’s body was left on the side of the road.

Brazel surrendered to Deputy Sheriff Felipe Lucero in Las Cruces, shouting, “Lock me up. I’ve just killed Pat Garrett!” Deputy Lucero locked up Brazel, called for a coroner’s jury, and rode to the location of the murder.

Related story from us: One of the men who killed Bonnie & Clyde was Bonnie’s secret admirer

Brazel’s trial for the murder of Garrett lasted only one day, on May 4, 1909. Carl Adamson never appeared at the trial as a witness, and Brazel was acquitted.