Childhood memorabilia can hold many fond memories, whether it’s the favorite teddy or the fluffy, irreplaceable blanket that we once snuggled with at bedtime. However, the most powerful reminders of our younger years can be the fairy tales we were told.

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, Peter Pan, and numerous others have shaped our imagination and even worked as moral lessons filtered through the playful characters.

Yet when these fairy tales’ origins are researched, a deeper and darker tone is found in many of them. One such tale is the “Little Red Riding Hood.” The earlier versions of this story differ from the widely known Grimm Brothers version.

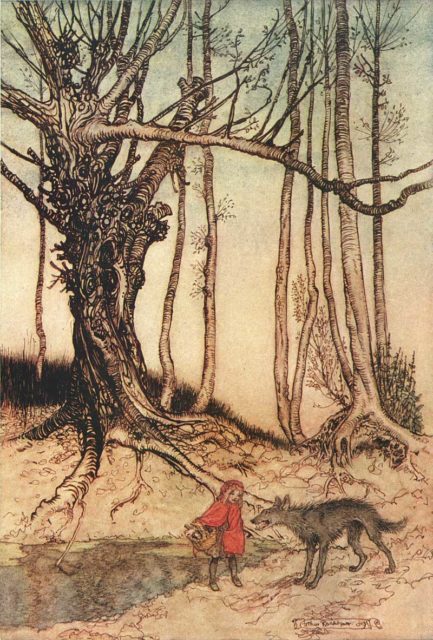

The popular version of this story presents a little girl with a hooded red cloak (according to the version of Perrault) or a cap instead of a hood (according to the Grimm version, known as Little Red-Cap). One day she goes to visit her sick grandmother and is approached by a wolf to whom she naively says where she is headed.

In the most popular modern version of the fairy tale, the wolf distracts her and goes to the grandmother’s house, enters it, and eats her whole. Then, he disguises himself as the grandmother and waits for the girl, who is also attacked when she arrives. Next, the wolf falls asleep but a lumberjack hero appears and cuts the wolf’s stomach with an ax. Little Red Riding Hood and her grandmother come out unharmed and put stones in the wolf’s body, so that when he awakens, he’s unable to flee and dies.

The origins of “Little Red Riding Hood” go back to the 10th century in France, where peasants told the story that was then passed along to the Italians, who were obviously enchanted by it. A few other versions with a similar title were created: “La Finta Nona” (The False Grandmother) or “The Story of Grandmother.” Here, the character of an ogre replaces the wolf that imitates the grandmother. Little Red is deceived into mistaking her granny’s teeth for rice, her flesh for steak, and her blood for wine, so she eats and drinks, and then jumps into bed with the monster and ends up eaten herself. Some versions include sexual implications and involve a scene where Little Red is asked by the wolf to take off her clothes and throw them in the fire.

Some folklorists have tracked down records of other French folk versions of the story, in which Little Red realizes the wolf’s attempted trickery and so she invents an I-desperately-gotta-use-the-bathroom-story to her grandmother in order to escape.

The wolf reluctantly approves but ties her with a string to prevent her from fleeing, but she still succeeds in escaping. Interestingly, these versions of the story depict Little Red Riding Hood as a courageous heroine who relies only on her wit to avoid the horror whereas the later “official” published versions by Perrault and Grimm include an older, male figure who saves her.

Dr. Jamie Tehrani, a cultural anthropologist, found several versions of “Little Red Riding Hood” dating back almost 3,000 years. According to him, in Europe at least, the earliest version is a Greek fable from the 6th century BC, attributed to Aesop.

In China and Taiwan, there is a tale that resembles “Little Red Riding Hood.” It’s called “The Tiger Grandma” or “Grand Aunt Tigress,” and it dates back to the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912). The motif, idea, and characters are almost identical, but the main antagonist is a tiger instead of a wolf.

The French folklorists and writer Perrault’s version of the story in the 17th century featured a young girl next door to a village who incredulously shares her grandmother’s address with a wolf. Next, the wolf exploits her naivety by asking her to get into the bed, where he then attacks and eats her.

This unhappy ending was later explained by Perrault himself, in order to cast any doubts away regarding the “moral” of the story. According to him, the story should be a forewarning for young, pretty girls to avoid strangers. Further, he noted that he chose a wolf to be a villain because wolves resembled people. Some of them might not be noisy or hateful but they deceive with their gentleness, enter the young girls’ homes and turn out to be fatal.

Two centuries later, the Brothers Grimm rewrote Perrault’s tale but also created their own variant, named Little Red Cap, in which an animal-skin hunter saves the girl and her grandmother. The brothers wrote a volume of the story in which Little Red Riding Hood and her Granny encounter and kill another wolf using a strategy supported by their previous experience. This time, Little Red ignored the wolf in the woods, Grandma didn’t let him enter, but when the wolf skulked around, they lured him with the smell of sausages from the chimney under which they previously put a manger filled with water.

The wolf plunged into it and drowned. In 1857, the Brothers Grimm concluded the tale as we know it today, reducing the somber undertones of other versions. Their practice was continued by the writers and adapters of the 20th century who, in the wake of deconstruction, Freudian analysis, and feminist critical theory, produced rather refined versions of the popular children fairy tale.