Nearly four decades before Robert Peary claimed to reach the North Pole and almost 60 years before Roald Amundsen did arrive there, another brave soul attempted to explore the Arctic, a man named Charles Francis Hall.

But his voyage ended tragically for him and unhappily for his boat and crew. All that remains after some 165 years is the lingering mystery of what–or who–killed Captain Hall.

The question is whether Hall poisoned himself with arsenic using it as medicine or if it was given to him intentionally by someone from the crew. The main suspect has always been the chief of the scientific staff, the German Dr. Emil Bessels, but evidence was never found.

Francis Hall was raised in Rochester, New Hampshire, where he learned to become a blacksmith. Later he worked as a newspaper publisher in Cincinnati, Ohio. However, around the 25th year of his life, Hall became interested in polar exploration and dedicated his time to studying the reports of previous expeditions.

Just as anyone else who shared the same interest, he got obsessed with the main puzzle of the time, what happened to John Franklin’s lost expedition and the 129 men on board. The British group had departed England in 1845 to explore the Northwest Passage.

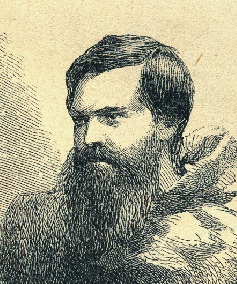

In 1860, Hall managed to become part of the crew on the whaler George Henry under the command of captain Sidney O. Budington. The ship sailed from New Bedford, but it didn’t get further than Baffin Island, where it was forced to winter overdue to hard ice. While there, Hall befriended some Inuits who told him stories about surviving members of Franklin’s lost expedition.

Upon his arrival home in 1863, Hall immediately organized a second expedition to seek the truth about the rumors he heard. He had troubles financing the expedition, but in 1864 managed to depart on the whaler Monticello with a much smaller expedition than he hoped for.

It lasted for three years. During that time, the captain found remains and artifacts from the Franklin expedition on King William Island. Although he was able to understand more about the fate of its members, he also determined that many of the stories about possible survivors were unreliable. He returned home in 1869.

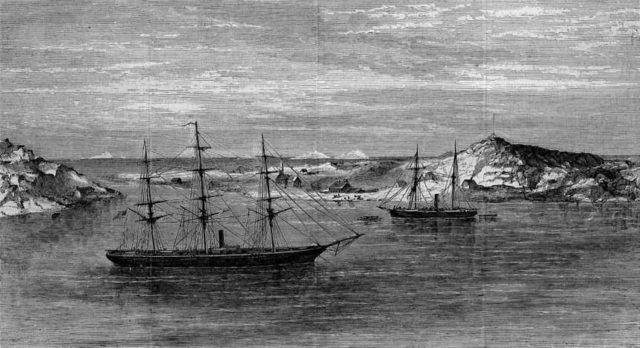

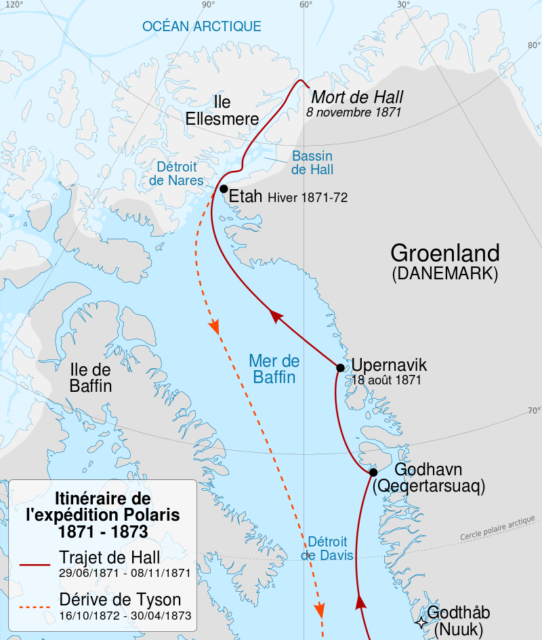

In 1870, the U.S. Congress authorized $50,000 for an expedition led by Captain Charles Hall to reach the North Pole. In June 1827, the Navy ship renamed as Polaris sailed from New York City. Followed by good weather, it reached Greenland by October, where the party led by Captain Hall was preparing for the North Pole. Although it all seemed to go as intended, things on the ship were not good. The captain failed to prove his authority to the crew and to gain their respect, even falling out with a few members. His relationship with Emil Bessels was especially hostile.

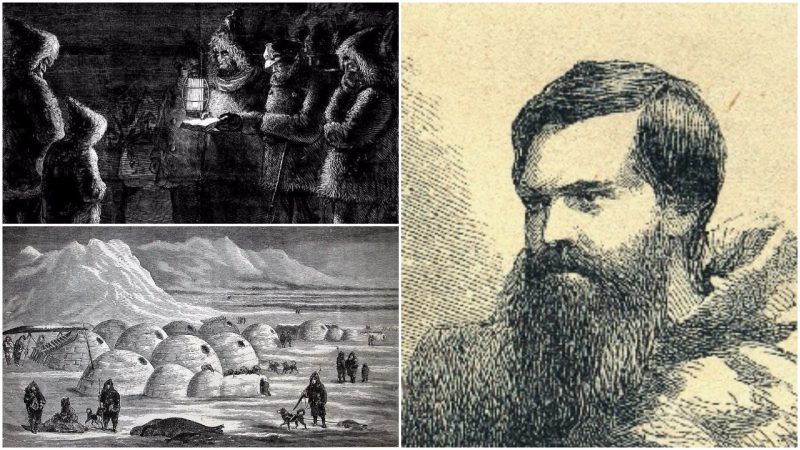

At the beginning of September, Polaris reached the northernmost latitude of 82°29′ N, which was the farthest north that any ship had arrived before. There were disputes over whether to continue even farther among the three main officers, but in the end, the ship was immobilized in ice on the shore of northern Greenland. During this time, along with three other men, Hall went on to scout a route further north for two weeks. On his return, he became violently sick, allegedly after drinking a cup a coffee.

Hall was in great pain. Over a week, the captain was vomiting, and while delirious, he blamed members of the crew for poisoning him. He died after a week of suffering. The crew gave him a formal burial onshore. The command of Polaris was given to Sidney O. Budington, who made an unsuccessful attempt for the Pole. The ship was wrecked, and the crew sailed south in two lifeboats until their rescue by another ship. They returned home via Scotland.

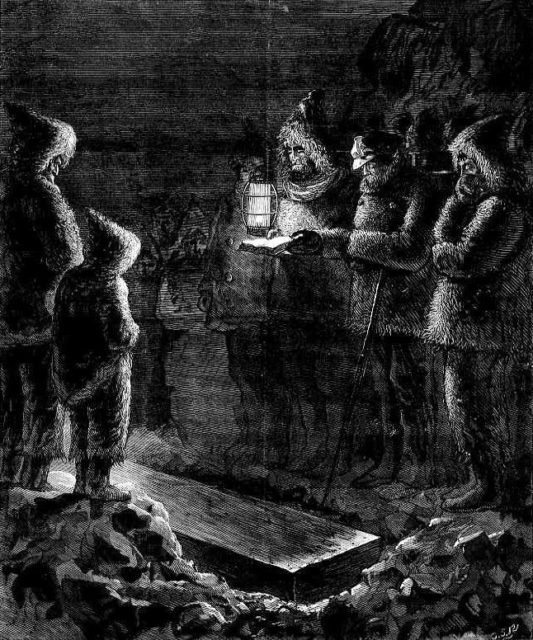

The official statement by Dr. Bessels was that Hall died of apoplexy. More than 100 later, in 1968, there was an expedition to Greenland organized by Professor Chauncey C. Loomis, during which Hall’s body was exhumed. The tests showed that the captain died of arsenic poisoning. Later, Loomis, who was Hall’s biographer, wrote Weird and Tragic Shores, in which he revealed the research. Although Dr. Bessels was always the main suspect for the captain’s death, arsenic couldn’t prove that Hall was murdered because back then the poison was also used as medicine.

An interesting article was written in 2015 by Professor Russel Potter from Rhode Island College, who has published a history of polar explorations, Arctic Spectacles. In his blog Visions of the North, Potter published that he saw an envelope at an online auction addressed to Miss Vinnie Ream. She was a famous sculptor most known for her statue of Abraham Lincoln.

Professor Potter had read Ream’s biography by Edward S. Cooper and encountered a very interesting paragraph which says that although Ream wasn’t known for long lasting relationships, she had an interesting encounter with Captain Charles Francis Hall. Her biographer states that the two of them met in early 1871, before Polaris sailed for Greenland. It would seem that Ream was attracted to the explorer and met him frequently over a period of two weeks. During their meetings, they often were accompanied by “the ship’s doctor, a small man who spoke English with a heavy German accent.“ It seems that both men were interested in the young sculptor, who was 25 years old at the time.

Bessels wrote her a letter, saying, “While thinking of you all the time and anticipating the pleasure of seeing you tomorrow, we received very unexpectedly an order requiring us possibly to leave early tomorrow. I will never forget the happy hours, which kind fate allowed me to spend in your company before starting our perilous and uncertain voyage.”

According to Potter, even though Hall was married, he might have spent some time with Ream before sailing to Greenland with Polaris. Although the professor is only pointing out an aspect that hasn’t been elaborated and which doesn’t prove anything, he wrote that it might have been another among the others motive for Bessels to poison Hall. The definitive answer to this mystery has not yet been found.