Some reasons for disputes between countries through history are as bizarre as human imagination can allow. In this particular case from the 1960s, Brazil and France went into conflict because of lobsters and who had the right to hunt them. Luckily, no one got hurt during this so-called “Lobster War.” So what was this all about?

The whole incident began in 1961 when some French fishermen who had fished successfully along the northwest coast of Africa decided to try their luck somewhere else. After trying out several locations, they finally found a good spot miles near Brazil’s coastline, away from where they had previously fished, lobsters thrived.

The sudden increase of French vessels in the area didn’t go unnoticed by the local Brazilian fishermen. They reported that a large number of French fishing boats were illegally catching lobsters off the coast of Pernambuco. The Brazilian Navy reacted to the complaints and Admiral Arnoldo Toscano ordered two small warships to verify the reports. They discovered that the allegations were correct and soon the Brazilian vessels asked that the fleet of French fishing boats returns to deeper waters, away from the coast of Brazil.

Unfortunately, the French were uncooperative and believed that they had every right to trap lobsters in those waters. They immediately sent a message to the French government, asking for their own fleet of military vessels in the area. This act forced the Brazilian army to mobilize all their ships in case something unexpected happened.

Although every conflict between two countries is a serious matter, we must admit that this one descended into the ridiculous. When Brazil mobilized its entire fleet, their Foreign Minister, Hermes Lima, stated the following:

“The attitude of France is inadmissible, and our government will not retreat. The lobster will not be caught.”

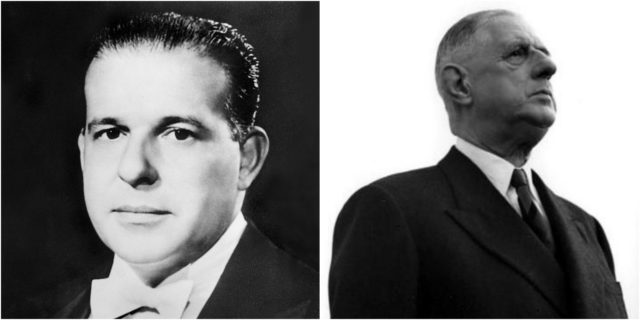

At the same time, Charles de Gaulle was furious about the whole situation. He believed that Brazil had acted disrespectfully towards France. On February 21, 1961, De Gaulle decided to dispatch their massive destroyer Tartu to keep the fishing boats safe. Tartu, however, never arrived to meet with the fishing boat fleet; it was intercepted by the Brazilian Navy on its way to the area.

The Brazilians had the upper hand in the whole situation. Their president, João Goulart, gave the French forces an ultimatum to withdraw within 48 hours, which they refused. After this, the Brazilians managed to capture a French vessel.

Although no shots were fired, the situation was tense. The Brazilians denied access to French fishermen within 100 miles of the Brazilian northeast coast. Their main argument was that lobsters “crawl along the continental shelf” and therefore they belong to Brazil. The French, on the other side, claimed that “lobsters swim” and therefore they belong to everybody that catches them in the ocean.

It was April 1963, and the conflict was still unresolved. Both of the disputed sides started to consider if a conflict over lobsters was worth a war. After both sides had decided that the best path was diplomacy, the issue was brought to an international court.

The “Lobster War” officially ended on December 10, 1964, after an agreement was signed by both Brazil and France. The whole incident was resolved by Brazil expanding its territorial waters to a 200-mile zone which encompassed the infamous lobster area. The agreement also allowed 26 French fishing ships to catch lobsters there over a period of five years.

Although the military conflict ended with the official agreement, the scientific argument continued until 1966. Both French and Brazilian scientists had their theories about the actual movement of crustaceans. The French still supported their theory that lobsters are like fish and they swim in the open ocean. Because of this reason they can not be considered as the property of any country. Brazil, on the other hand, claimed the opposite stating that lobsters, unlike fish, remain down on the ocean floor.

This whole conflict maybe sounds farcical, but ultimately it played a big role in establishing United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.