Michelin, one of the four largest tire manufacturers in the world alongside Goodyear, Continental, and Bridgestone, is a mass-scale producer of tires for the automotive and cycling industry. It also makes aviation equipment and tires for space shuttles.

Through tireless innovation, the French company gained recognition as one of the greatest inventors in the field, and they hold the patent rights to inventions such as the pneurail—a tire built for trains meant to run on rails—as well as removable and radial tires.

And … Michelin also publishes an annual guide that chefs around the world labor endlessly to impress so that they can win that all-important validation: the Michelin star. To achieve three stars is the goal of a career.

For the Michelin Red Guide, the writers map restaurants and hotels across Europe and rate a very select few with Michelin stars for excellence in service. They’ve been doing this for more than a century and as time went by, the guide (the oldest of its kind) grew to be the most notable reference for fine establishments. The earning or loss of a star can have a dramatic impact on restaurants’ futures. A French chef, Bernard Louiseau, shot himself in 2003 when newspapers hinted his restaurant might lose its three-star status.

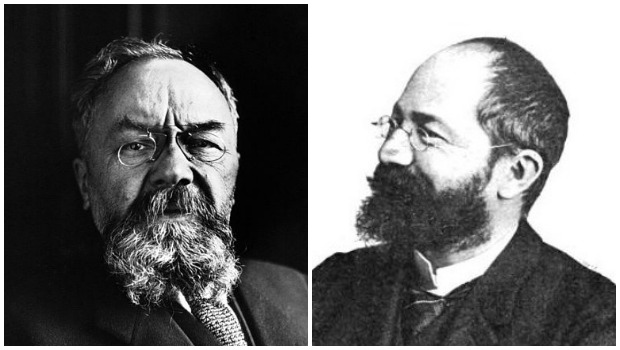

It all began in 1889 when the Michelin brothers, André and Édouard—who operated a rubber factory in Clermont-Ferrand—lent a hand to a random cyclist who showed up at their workplace with a flat pneumatic tire. At that time, this was not an easy fix because the tire stood glued to the rim. It took forever for them to remove it, only to then leave it to dry out for the rest of the night. The whole process took no less than a full day. Afterward, when everything was ready, they made a test drive that failed miserably, encouraging them to try an unusual approach and create their own tire, one that would not need to be glued to the rim.

Soon after, the first was ready, and in 1891 the brothers patented their removable pneumatic tire for the Michelin Corporation. Little did they know that by doing so, they set in motion a great odyssey of perfecting modern transport solutions.

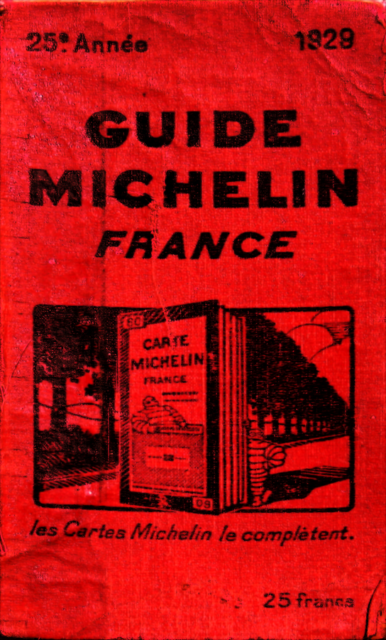

In the meantime, the automotive industry was developing rapidly, so naturally, the brothers aspired to profit from it. But by the 1900s, fewer than 3,000 cars were on the road in France, so in order to increase the demand for cars (and therefore tires), the brothers cleverly composed and published a booklet called the Michelin Guide. It was intended for French travelers, cyclists, and motorists, aiming to provide valuable information, such as maps of tire repair shops, auto mechanics, hotels, and petrol stations throughout France, as well as offering replacement instructions and tutorials.

This all-in-one publication was totally free. They printed more than 35,000 copies, almost 10 times more than the number of cars driven in France at the time. The Michelin brothers’ plan worked; in 1904, they printed a new guide for Belgium.

By 1911, Michelin Guides for many nations and larger regions were published, including Algeria and Tunisia in 1907; the Alps and the Rhine (northern Italy, Switzerland, Bavaria, and the Netherlands) the year after; Germany, Spain, and Portugal in 1910; and the British Isles in 1911. That same year they decided to release a special guide for “The Countries of the Sun” (Les Pays du Soleil), which included northern Africa, southern Italy, and Corsica.

After the end of World War I, new editions were published and continued to be given away for free. This trend lasted until 1920, when André Michelin apparently saw copies of their guides being used to prop up a workbench while visiting some tire retailers. After that, based on the premise that “man only truly respects what he pays for,” they decided to put a price on the guide, charging about 750 francs for it, or $2.15 in today’s money.

People were hooked on the guides, so they shelled out the money. With this, the magazine brought in an additional cash flow, so the Michelin brothers made a decision to completely eliminate the advertisements from the pages, tweaking their guide in the process.

First and foremost, they listed restaurants by specific categories. Secondly, seeing the ever-growing popularity of the restaurant section, the brothers recruited a team of investigators so they could visit, review, and comment on the service they received. Always anonymous, they would visit the selected restaurants simply as guests.

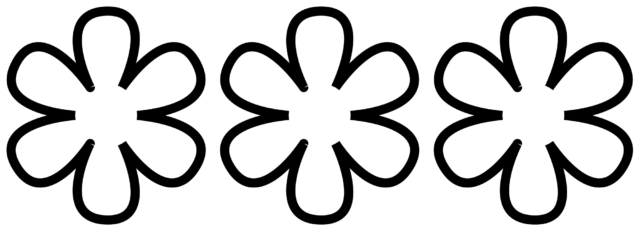

By 1926, the Michelin Guide started to give stars alongside the reviews to fine dining establishments. At first, only a single star was given to the ones worthy enough to get one, and after only three years, the three-star system still in use today was born:

(One Star): “A very good restaurant in its category”

(Two Stars): “Excellent cooking, worth a detour”

(Three Stars): “Exceptional cuisine, worth a special journey”

In November 2005, Michelin finally produced the first American guide, mainly focusing on New York City. As many as 500 restaurants were included, located in the city’s five boroughs as well as 50 hotels in Manhattan. Two years later, a Tokyo Michelin Guide was launched, the same year that the guide introduced the Étoile magazine.

The following year, Juliane Caspar, a German restaurant owner, was appointed as chief editor of the French edition. She had previously edited the guides for Germany, Switzerland, and Austria. With this, she became the first woman and the first non-French person to ever hold the editor’s seat for the French guide, after which the German newspaper Die Welt commented, “In view of the fact German cuisine is regarded as a lethal weapon in most parts of France, this decision is like Mercedes announcing that its new director of product development is a Martian.”

In the last five years, headlines challenging the importance of the Michelin Guide have appeared. “Michelin Guide Has Lost the Plot,” declared one. “Are Michelin Stars Over-Rated?” demanded another.

Paul Bocuse, a world-renowned chef based in Lyons who, among many other culinary accomplishments, invented truffle soup to serve at a French presidential dinner, and whose restaurant, l’Auberge du Pont de Collan, is one of the very few in Europe to receive three stars, once said, “Michelin is the only guide that counts.”

Clearly, that judgment stands.