Since ancient days, people have developed sophisticated weapons to fill their arsenals. In ancient Egypt, the khopesh was a notoriously deadly sword on the battlefield. A khopesh would typically be cast out of a single piece of bronze that was quite heavy, and it looked like a cross between a battle ax and a sword. Even Ramses II is portrayed as wielding one of these.

A Japanese officer of the Edo era would make great use of a sodegarami (the word itself means “sleeve entangler”). This weapon looked like a spiked pole, and it allowed the officers to confront any antagonist with a quick twist, bringing the attacked person to the ground but not necessarily inflicting severe wounds.

When it comes to the Aztec warriors, perhaps their best asset on the battlefield was the macuahuitl. Known as the Aztec sword, this weapon was not a real sword cast in metal but made from oak wood. Its edges were set with obsidian blades (volcanic glass), and Aztec warriors used these to slash throats and inflict painful wounds that caused heavy bleeding.

When Cortés arrived in Central America, he certainly witnessed the strength of the Aztecs on the battlefield. Chronicles of his battles and similar historical documents tell that the Aztecs were fearsome people. Their society and culture were largely built on warriorhood.

Both the jaguar and the eagle were emblematic predators that added to the Aztec culture, and warriors would typically dress to look like one of the two. They believed such appearance would spread fear among their adversaries. If a new warrior was to join the Aztec battle groups, he could do so only if he captured an enemy soldier first.

The Aztec had a well-thought-out system on how the military should function, and a well-developed strategy for the battlefields too. The Aztec warriors who used the macuahuitl would step forward during a battle only when the archers or slingers advanced close to the adversary. In a close encounter with the enemy, the macuahuitl was their best asset in hands.

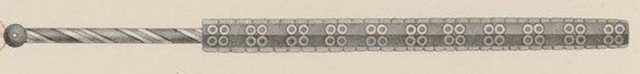

Resembling a cricket bat, the macuahuitl had a length typically extending some three and a half feet. While numerous examples of this weapon were managed with one hand only, there were others who required two hands to grab and fight.

Depending on its size, the weapon had between four and eight razor-sharp blades along each side, but this varied, with some macuahuitl embracing a complete single edge formed by the unusual volcanic material. No matter the design, the obsidian could not be pulled out. The Aztecs would wield their swords with short and chopping movements, and, as many accounts suggest, they cut off some heads.

Besides the macuahuitl, the Aztec made use of the tepoztopilli, one more weapon carved out of wood and fitted with obsidian blades. However, the tepoztopilli was more like a type of polearm. It was spear-like, with a large wedge head on the front, and at five to six feet long, the entire piece was a bit longer than the macuahuitl.

Cortés’ conquistadors certainly had plenty of opportunities to see the power of the Aztec weaponry demonstrated first hand. Several of the Spanish horse riders reported that the Aztec swords were able to decapitate not only a human head but that of a horse. The blades would inflict a wound so deep in the animal, its head would cleave off to hang only by the skin.

Contrary to popular belief, the deadly macuahuitl was not an invention of the Aztec themselves, but rather a weapon widespread among distinct groups of Central Mexico and likely in other places of Mesoamerica as well.

Even Christopher Columbus was fascinated by the strength of this weapon when he encountered it after reaching the Americas. He gave orders to his people to collect a sample to show back in Spain.

Today, there aren’t any original macuahuitl surviving, only various re-creations of the weapon based on knowledge extracted from contemporary accounts and illustrations produced during the 16th century or earlier.

Read another story from us: Goose hunters in Iceland track down a 1,000-year-old Viking sword

It is believed that the last authentic macuahuitl was destroyed in a fire in the Real Armería de Madrid, where the weapon was kept for a long time next to the last original tepoztopilli.