The date was January 15, 1947. During the morning hours of a chilly Wednesday–rather grim for Los Angeles–resident Betty Bersinger, taking a stroll with her daughter, spotted what she thought was a mannequin tossed onto the ground, but was a naked, dead body. Dumped in an abandoned lot in Leimert Park, the body of the young woman appeared to have been sliced in two—detached somewhere below the ribs—and her blood had been drained from her body intentionally and precisely.

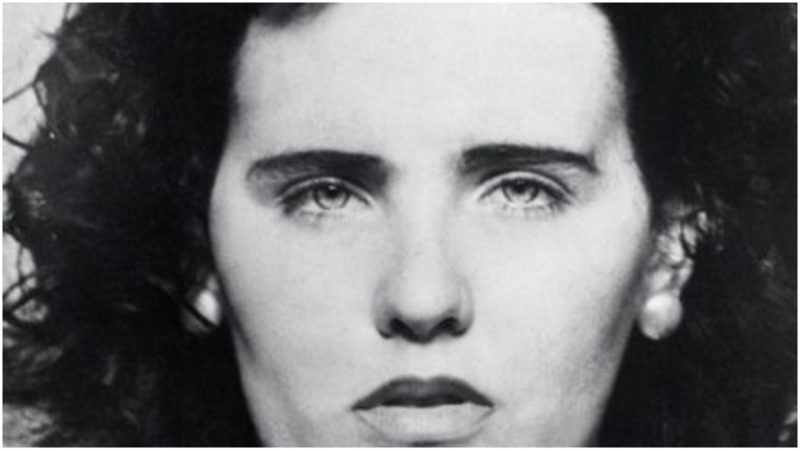

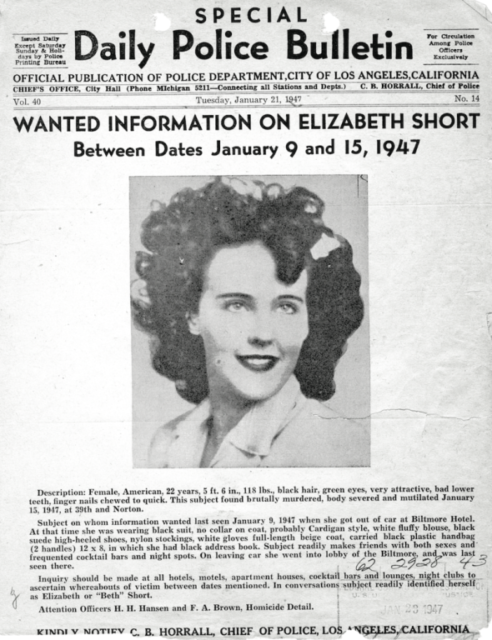

The case quickly filled up newspaper headlines across the country. The corpse was identified as 22-year-old Elizabeth Short but the press chose the name Black Dahlia after a film noir released shortly before the murder entitled The Blue Dahlia.

Elizabeth Short was a beautiful dark-haired woman, and her death would acquire a strangely iconic status over the years. It sparked numerous media outputs, books that focused on the case, films, and, absurdly, even video games; a Black Dahlia cocktail is served at the Biltmore Hotel, where Short was last seen alive by witnesses, a couple of days before she was made the victim of the gruesome killing. In the days, months, years, and even decades following January 15, 1947, investigators took on lengthy and exhaustive investigations. Amid a whirlpool of information and hundreds of suspects, many working on the case would get lost between true and false statements.

The horror of the crime had a strong impact on the community, “I just can’t imagine someone doing that to another human being” were the words of Brian Carr, one of the detectives from the L.A. Police Department on the Dahlia case.

Not only had her blood been drained out of her body but her intestines were also removed and her mouth appeared to be slashed from one ear to the other. After being slaughtered in such a sinister way, her killer made sure to wash the body so as to clean off any incriminating evidence, but he certainly did not stop violating the body, even though it was already lifeless.

Whoever the killer was, he was somebody looking for publicity, as sickeningly he would proceed to distribute packages containing Elizabeth’s clothes to media outlets, as well as mocking letters signed the “Black Dahlia Avenger.” This lasted throughout the investigations and there were detailed newspaper stories about it.

For a time, investigators believed that while hitchhiking, she had eventually ended up in the car of her sadistic killer. Later on, the theory was that she was murdered by someone she knew. A majority agrees that the killer was somebody who was familiar with medicine and human bodies.

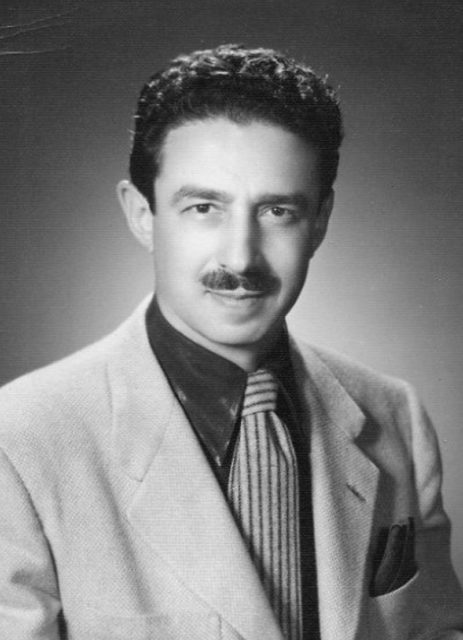

This brings us to one of several names that remain on the current suspects list, even seven decades after the murder: Doctor George Hodel.

In recent years, Steve Hodel, son of George Hodel, drew suspicion to his father as the cold-blooded killer. A L.A. Police Department detective in retirement, the younger Hodel alleged this after discovering photographs of a woman he believed was Short among the possessions of his late father.

Steve Hodel came to think that his father employed his medical knowledge in order to kill Short, along with other victims, before leaving for Asia in 1950. The year before that, Dr. George Hodel was put on the police watch list after his 14-year-old daughter had him accused of molesting her. There was later a trial on the incest case.

A physician who specialized in public health and sexually transmitted diseases, Dr. Hodel reportedly had made some incriminating statements while he was under surveillance, most notably, “Supposin’ I did kill the Black Dahlia. They couldn’t prove it now. They can’t talk to my secretary anymore because she’s dead.”

The younger Hodel would conduct further research through the years and even came up with samples of soil that tested positive in tests for disintegrated human remains. Although George Hodel makes for a reliable suspect in the case, authorities are not saying for sure whether he was, indeed, Short’s killer. He died in 1999.

One of the more far-fetched theories has it that filmmaker Orson Welles was a suspect. At least, that’s what one publication from 1999 says, written by Mary Pacios, who used to be a neighbor of the Short family in Massachusetts (where Elizabeth originally came from).

Another theory: a 2017 book by Piu Eatwell, a British author, implying that perhaps it was an entire group that thrived in 1940s L.A. that could have been involved in Elizabeth’s case: a ring of criminals, corrupt police officers, and the wealthy businessman Mark Hansen, who was supposedly one of the men Short was seeing in the months before being killed.

According to this theory, the vicious circle exploited Short, who in reality appeared to be helpless, a sharp contrast with the image of her as a femme fatale.

Just like many other young women her age, Short had wished to become an actress, which was the reason she moved to Los Angeles. Like most of the other women drawn to Hollywood, she got nowhere in the movie business. Having no real friends or family to support her in the city, she would often find herself lonely, broken, and without proper shelter for the night.

That’s why she would often get involved with different men, including Hansen. Danish by origin, he reportedly owned a club in downtown L.A., and Elizabeth stayed at his place on at least two occasions. The relation between the two had allegedly reached a point of high tension, and Hansen threw her out at one point.

Elizabeth likely was angry about Hansen’s decision, and Eatwell’s argument is that Hansen then sent one of his associates to take care of her, that person reportedly being Leslie Dillon. Supposedly, Dillon had been employed as an assistant to a mortician before the murder of Elizabeth Short took place, meaning he probably had the knowledge needed in order to slice her body in the way that it was done. Whether Hansen was aware that Dillon was a vicious psychotic or not would remain uncertain. Furthermore, if this theory is true, Hansen would have certainly used some of his connections to help redirect the investigations away from himself and those connected to him, including Dillon.

As Eatwell’s book goes on to say in support of this theory, Dillon had revealed small details in his statements that were also fairly incriminating, such as the fact that Elizabeth had a rose tattoo on her thigh, which in the process of her brutal butchering, was removed. Dillon later made comments that he wished to work on a book concerning the killing.

The names of George Hodel, Mark Hansen, and Leslie Dillon are only three of the 11 names that compose the list of current suspects who may have committed this now seven-decades-old murder. As the years go by, it becomes harder and harder to close the case of who the killer really was and give Elizabeth Short the justice and closure she deserves.