For many of us, it is hard to find just one partner, but for Matthias Buchinger, the limbless German magician of the 17th century, it was easy as one, two, three. Or 74, if we count the ladies he romanced.

He was married four times actually, with whom he fathered 14 children, and as far as rumors go, he was quite the ladies man back in his prime, with some 70 mistresses and a lot of sleepless nights. The man was an expert marksman, blindfolded knife thrower, skilled inventor, and an illusionist.

So it might be these qualities that made him a lady magnet. Or perhaps it was because he earned a reputation for being a real maverick who won every poker game he ever played. Or maybe, just maybe, it had something to do with the fact that he could sing a serenade as a true gentleman would for a lady and forever engrave her face in an intricate little miniature picture afterward, with no hands nor fingers to do it, leaving her spellbound of the little man’s magical prowess and enchanted by his chivalry.

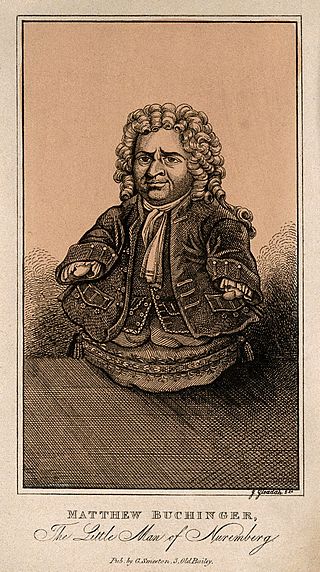

Although he was little, no more than 29 inches at most, he managed to grow so much in fame and popularity that he made himself stand out from the rest. But not for his short stature and being a “funny little freak” with stubs for arms and legs, but because of all the things this little man could do without them.

Buchinger was born with a congenital malformation of the limbs and had no arms below the elbows or legs below his upper thighs. His parents immigrated to a small place near Nuremberg, Germany, shortly before he was born on June 3, 1674. To avoid ridicule of their “freakish” son, they kept him hidden as much as possible for the first 20 years of his life.

Who could blame them at that time period? His genetic disorder, now identified as phocomelia, was unspecified and many people viewed deformity as the Devil’s work. There are even stories of disabled people, especially dwarfs and midgets, being hunted down for sport. Or, out of fear and superstitious belief that their looks were a clear indication of witchcraft, they were burned without a trial. So, while his eight brothers and sisters were playing outside in the sun, Buchinger made good use of his time in concealment to develop impressive skills.

He grew up to be a multi-talented and intelligent man, a polymath and musician who was celebrated for the dexterity of his small flipper-like appendages that served as hands. By the age of 20, he began to tout himself as a fairground act. He must have been a brilliant showman, for he soon became popular with audiences for his clever performances.

A prodigy of a man with extraordinarily broad and comprehensive knowledge, and not just in drawing and carving, which was his most prized asset and remained his main income throughout his life, but in slight of hand magic tricks (minus the hands), fencing, bowling, shooting, knitting, archery, and playing a whole variety of musical instruments. And he did it all to an exceptional standard.

After reading about Buchinger in a book by the magic historian Milbourne Christopher, Richard Jay Potash, more commonly recognized by his stage name, Ricky Jay, dedicated no less than 30 years of his life to digging up facts about Buchinger’s wondrous and inspirational existence. In 2016, this American master magician arranged the exhibition Wordplay: Matthias Buchinger’s Inventive Drawings from the Collection of Ricky Jay at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

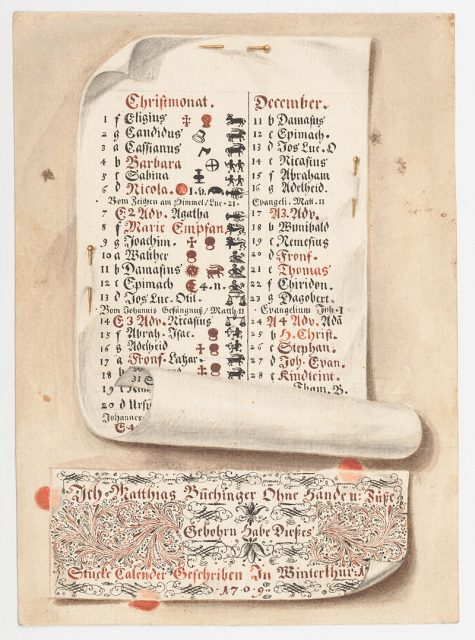

The display showcased the first collection of Matthias Buchinger’s artistic work. There were a variety of intricate drawings, miniature wood carvings, and finely detailed ships-in-bottles. Excitingly for art historians, he was inclined to sign his work Matthias Buchinger – born without hands and feet in small letters, often with a date and location.

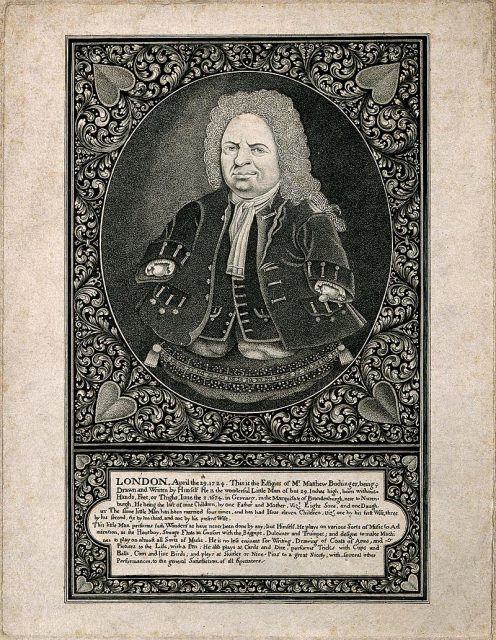

The exhibits included some wonderful examples of a talent he excelled in the most: micrograpy. This branch of calligraphy, the art form of drawing pictures with letters so small that one might need a magnifying glass to read them, developed possibly as far back as the 9th century. It is unclear exactly how he accomplished such astonishingly precise works of art. It has been postulated that he was aided by custom-made devices that he designed himself.

Some of the most fascinating pieces include a picture of his family tree where the trunk is Buchinger himself, the large branches his four wives, and the smaller ones their children; a highly detailed portrait of Queen Anne; and his most famous one, a self-portrait drawing in which his large wig is made up from tiny transcriptions of seven psalms and the Lord’s Prayer.

As part of the exhibit, Ricky Jay offered a memoir of his research, Matthias Buchinger: The Greatest Living German by Ricky Jay, Whose Peregrinations in Search of the ‘Little Man of Nuremberg’ are herein Revealed, in which, based on the things he found, he gives a detailed description of Buchinger’s life and how he succeeded in all these things.

According to Jay, the Little Man of Nuremberg first began working in sideshows in his homeland, then he went on to become a celebrity throughout Europe, even entertaining royalty. After traveling to Denmark, Holland, and France, Buchinger found himself a lucrative niche in England, where people had a particularly strong fascination with what was considered grotesquerie and freakishness. At the peak of the “freak show” golden age in Victorian London, events that celebrated such carnival acts such as the Bartholomew Fair and Lord Mayor’s Show were hugely popular.

People came to see his curious ability to achieve “with his stumps what many could not do with their hands and feet so well,” as one eyewitness report from 1731 spoke of him. He became a legal resident in England but continued to travel and perform all over Europe. Jay has even unearthed an entry in the royal accounts from the Palace of the Tuileries in France that details his payment for entertaining the boy-king Louis XV in 1717.

Related story from us: Lavinia Warren’s wedding to Tom Thumb attended by 10,000 in Civil War-era NYC

At last, he settled as a wealthy man at County Cork, Ireland, along with his fourth wife. By then he had passed almost every corner of the kingdom and was no longer a novelty. Following his death in 1739, the Dublin Penny wrote that he died “at an advanced age, in easy circumstances, and much respected.” He was 65 and asked formally for his body to be donated for scientific purposes.

In the words of Buchinger himself: “I do believe there never was a person born without hands or feet that can do what I can and is likely there may never be another.”