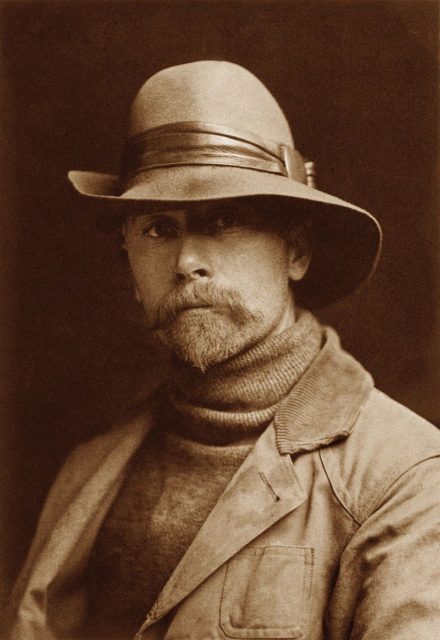

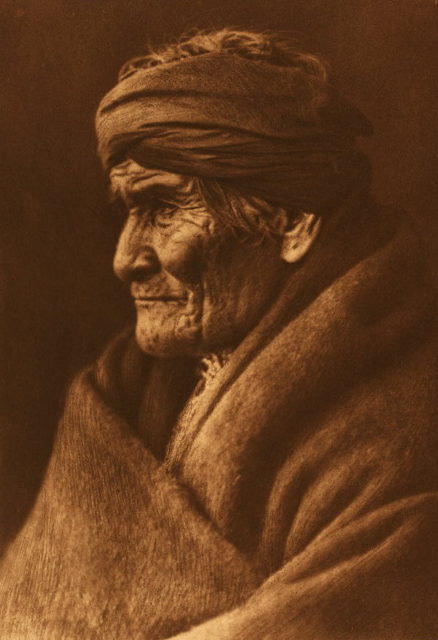

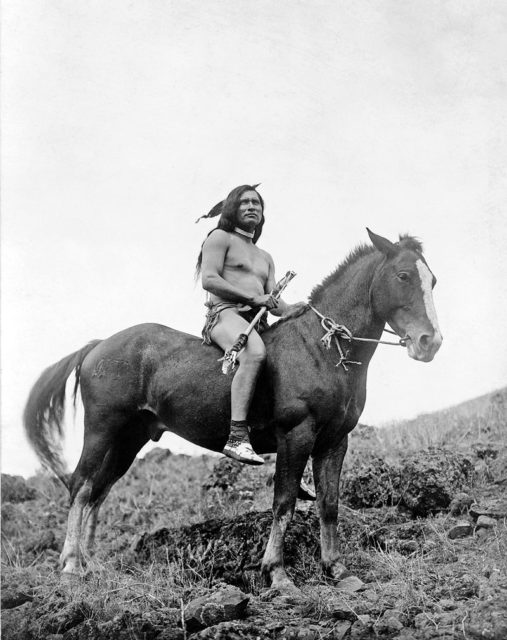

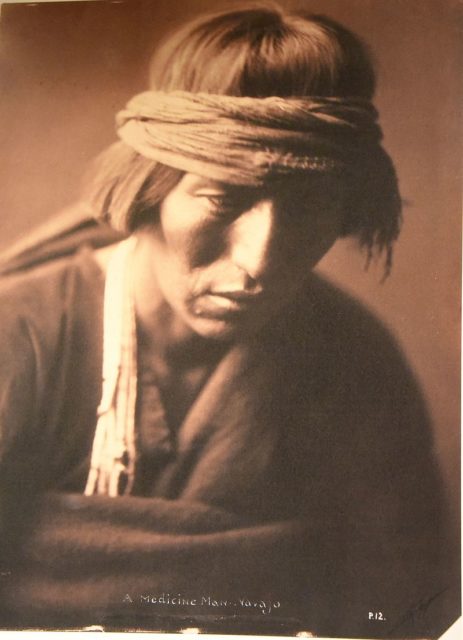

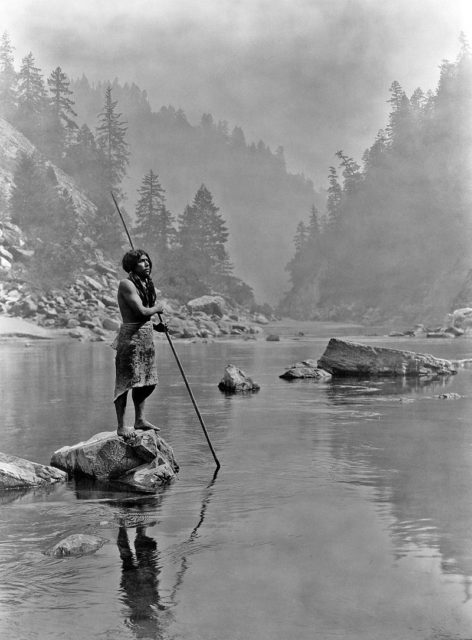

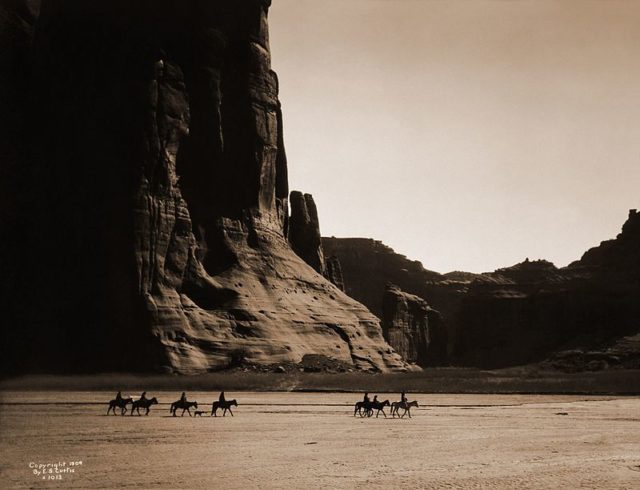

Edward S. Curtis gave up school in the sixth grade and decided instead to build his own camera. From that moment on, this was to be his life’s passion and through it, the Wisconsin native became enthralled by Native American culture, dedicating his career to recording the lives of Native Americans. He spent many years writing down their oral history, along with his observations, making voice recordings of their music and stories, and taking thousands of photographs.

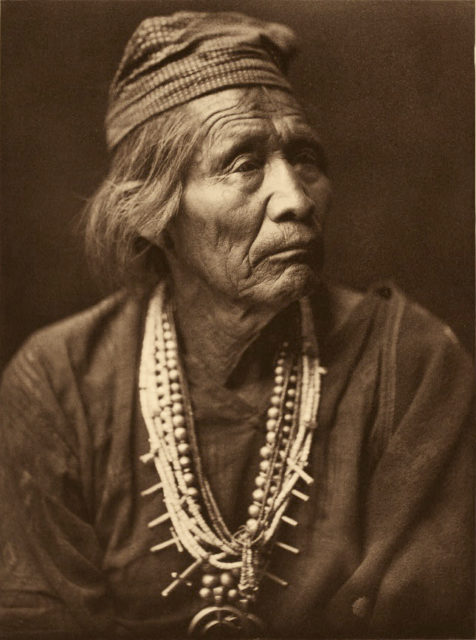

Curtis’ ethnographic recordings are the only available source for some of the native North American cultures. His work is an essential part of many universities and institutions’ collections and original prints of his photos have been sold at auctions, such as in 1972, when a whole set was sold for $20,000; and again in 1977, when another was sold for $60,500.

In 1885, the 17-year-old Curtis became an apprentice photographer in Minnesota. Two years later, his family moved to Seattle, where he got himself a new camera and partnered up with Rasmus Rothi, with whom he paid for an existing photographic studio. After six months, however, Curtis found another partner, Thomas Guptill, and together they established a new studio which they named “Curtis and Guptill, Photographers and Photoengravers.”

He made his first portrait of a Native American in 1895. It was a photograph of Princess Angeline, also known as Kikisoblu, the daughter of Chief Sealth of Seattle. Three years later, the National Photographic Society exhibited three of Curtis’ photos, two of which were images of Princess Angeline, “The Clam Digger,” and “The Mussel Gatherer.” The third was “Homeward,” an image of Puget Sound, earning him the gold medal and the grand prize at the exhibition.

That same year, in 1898, while taking photos of Mt. Rainer, Curtis had an interesting encounter with a group of scientists who were looking for direction in their work. He helped them and befriended one, George Bird Grinnell, an anthropologist and historian who then dedicated his career to studying the Native American peoples. As a result of this friendship, in the following year, Curtis became a member of the Harriman Alaska Expedition as its official photographer.

Lacking formal education, Curtis attended the lectures that were given on the ship each night during the voyage. Interested in Curtis’ work, in 1900, Grinnell invited him to join an expedition in Montana where he could make photos of the people of the Blackfoot Confederacy.

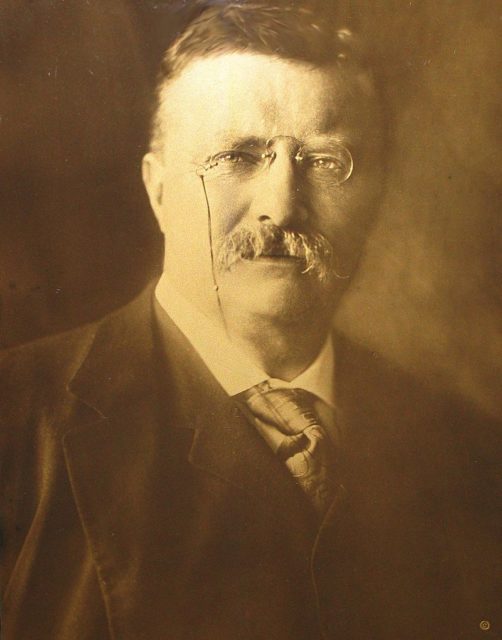

In 1906, Curtis received $75,000 in funding from J. P. Morgan to produce a series on Native Americans. Even though the sum sounds huge, the money was to cover a 20-year project during which time the photographer wouldn’t receive any salary and would have to provide Morgan with a repayment of 25 sets and 500 original prints.

Passionate about the project, Curtis secured funding and employed several people to help him, one of whom was William E. Myers, a former journalist who recorded the languages of the Native Americans. Another member of his team was Frederick Webb Hodge, an anthropologist who had previously researched the Native American peoples of the southwest.

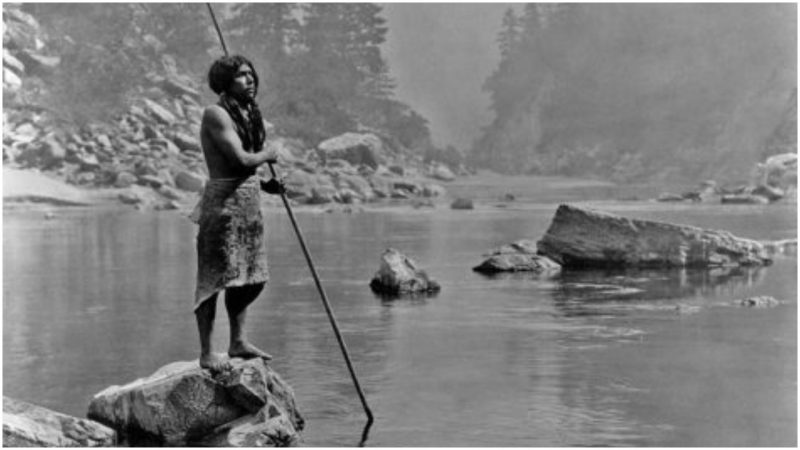

The team worked with great respect, passion, and dedication. Curtis’ idea was to record as much of the traditional life of the Native Americans as possible, not only to photograph them. He believed that the culture and lives of that great people had to be collected as otherwise the opportunity would be lost, and sadly he wasn’t wrong.

Besides the 222 complete sets, Curtis took 40,000 photos of the members of more than 80 tribes. He wrote down their histories, described their ceremonies, customs, recreational activities, clothes, housing, and their traditional foods. He recorded Native American language and history on more than 10,000 wax cylinders. In most cases, his documentation is the only written, recorded history there is about the tribes. In 1973, Curtis’ work was exhibited at the Rencontres d’Arles festival in France.

During his fieldwork in 1906, Curtis also used motion picture cameras to record “The North American Indian.” In 1910, he also collaborated with the anthropologist George Hunt, although their extensive work with the Kwakiutl remains unpublished. In 1912, Curtis went on to make a film about the Kwakiutl tribe of the Queen Charlotte Strait region in Canada. In the Land of the Head Hunters was the first feature-length film in which the whole cast consisted of Native North Americans. It was a silent film with a score composed by John J. Braham and even though it was praised by critics, the film made only $3,269 in its initial run.

In 1892, Curtis married Clara J. Phillips and they had four children. While he was obsessively working on his project “The North American Indian” for almost a year, Curtis was absent from home while Clara was managing his studio and the children. This led to an estrangement, and she filed for divorce in 1916. As her part of the settlement, Clara received the photographic studio and all of Curtis’ original camera negatives. Accompanied by his daughter Beth, Curtis destroyed all of the original glass negatives before they could become the property of his ex-wife.

His daughter went with him to Los Angeles, where he opened a new studio in 1922. He was desperate for money and took a job as an assistant cameraman for Cecil B. DeMille. He was uncredited, but in 1923, he became the assistant cameraman at the filming of The Ten Commandments. In 1924, he sold the rights to his movie In the Land of the Head-Hunters to the American Museum of Natural History. In 1928, he also sold the rights to his project “The North American Indian” to J. P. Morgan, Jr.

Sadly, Curtis never got back on track with his work. He died of a heart attack at the age of 84, in the home of his daughter. However, interest in his work was revived in the 1970s, when major exhibitions of his work were presented at the University of California, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and Morgan Library & Museum.