The dose makes the poison, the ancient pharmacists once said. Even the most poisonous fauna that Mother Nature produces can be beneficial if used judiciously. The word poison may evoke thoughts of sudden, painful death, but for centuries herbalists and healers exploited the power of natural toxins and venoms as medicine.

Moreover, it is no secret that some “notorious” substances played a hallucinogenic and psychotropic role too. Most of us are quite familiar with the fact that Coca-Cola’s older variants (1886-1929) contained cocaine in varying amounts. At the time cocaine was considered a legal medicine, and it wasn’t the first drinkable product that used the coca plant in its formula.

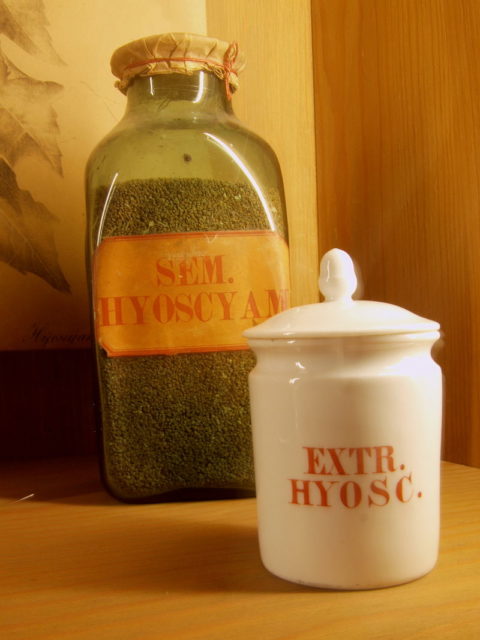

Among the numerous plants of this kind was henbane, which during the Middle Ages was widely known as “the insane seed that breedeth madness,” although today it is recognized for its contribution to the development of modern medical painkillers.

Henbane, whose botanical name is Hyoscyamus niger, belongs to the nightshade (Solanaceae) family of flowering plants. This group includes innocent plants like potatoes and tomatoes as well a number of other poisonous herbaceous plants such as Mandrake, daturas, and belladonna. Historically, henbane is recorded as a “witchy” plant. Its magical qualities hold a place in ancient folklore for it was found in recipes for witches’ “flying ointment.”

More benevolently, in the medieval period, henbane was an essential component of the “soporific sponge,” used as an anesthetic for surgery. Scientists are unsure of the plant’s origin, but the earliest known written record of henbane is in the published account of Nicholas of Salerno, an Italian physician who contributed significantly to medicine during the 12th century. These accounts were printed in 1470, in the book titled Antidotarium of Nicolaus Salernitanus.

It contains a recipe for a formula of opium, henbane, and hemlock, augmented with mulberry juice, mandrake root, ivy, and lettuce. A sponge was soaked in the juice of these plants, then dried and held in stock until needed for a patient. Before surgery, the sponge would be wetted and placed over the patient’s nose and mouth. According to the records, these narcotics assured 96 hours of unconsciousness.

The look of henbane’s seed is suggestive of another interesting use in ancient Anglo-Saxon medicine. The heads of the seed resemble a piece of jawbone complete with a row of teeth. Therefore, it isn’t strange to learn that this plant was used in ancient dentistry as it quickly relieved a toothache with its hallucinogenic, soporific effects. The seeds were heated over charcoal until they produced fumes, which were inhaled. In addition, the ancient Egyptians are said to have smoked henbane for dental problems. However, their native henbane was much concentrated than the European version.

According to the ethnographic analysis by Sally Hickey, German folklore also contains records of henbane, associating it with witchcraft and witches, who were believed to have used it to raise rainstorms or curse people and their lands and livestock with sterility.

One of the most intriguing uses of henbane was as a flavor in beer, a tradition with an apparently long history, since the evidence of its use was found in at least one Neolithic site in Scotland and in the resurrected recipes of Celtic beers, which are over 2,000 years old. Before the general adoption of hops to flavor beers and ales, the ancient brews were made with a wide variety of flavorings and enhancers, including henbane, which supposedly made beer more intoxicating.

The ill fame of henbane, however, doesn’t end here. It is presumed to be the poison chosen by Shakespeare in Hamlet, used in act 1, scene V, to kill Hamlet’s father. Various versions of the text use the term hebenon or hebona, in the line quoted as “with juice of cursed hebenon,” leading some scholars to assume the reference is to henbane.