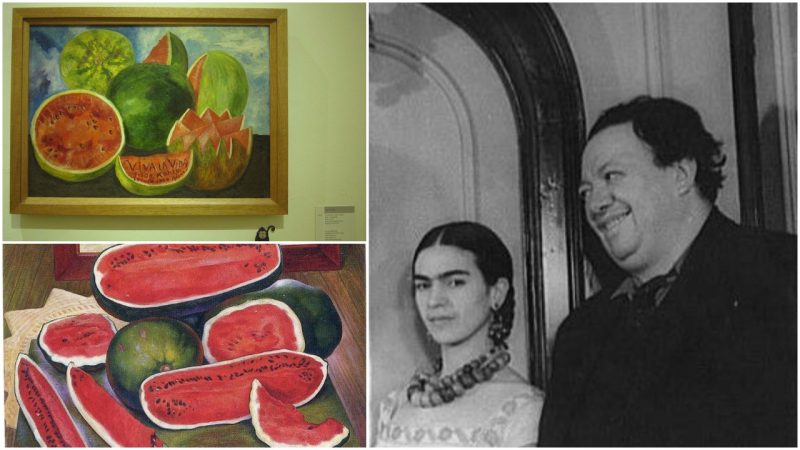

Eight days before her death in July 1954, Frida Kahlo is said to have completed what is popularly thought to have been her final painting: a still life of cut watermelons originally entitled Sandías (Watermelons). Upon the flesh of the piece of fruit located in the bottom center of the painting, Kahlo inscribed her parting declaration by which the painting would become best known: Viva la Vida (Long Live Life).

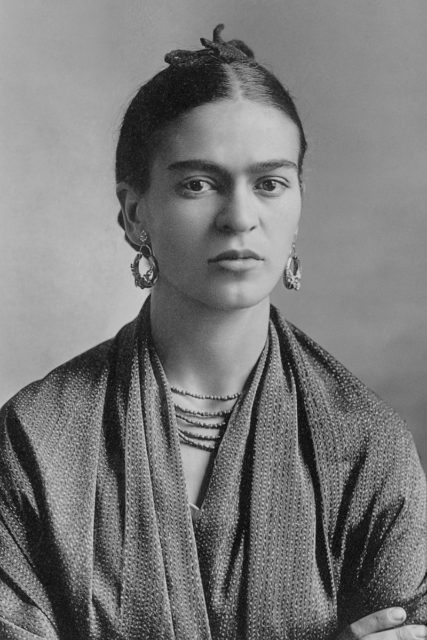

It is a final homage to a life racked with debilitating pain caused by a near fatal traffic collision in 1925, leaving Kahlo with permanent health complications that plagued her throughout her life. In spite of these traumas, Kahlo’s life was filled with endless artistic expression and cultural exploration that produced art which would go on to influence a whole new wave of Mexican creative culture.

Her physical condition, along with her tumultuous marriage to famed Mexican mural painter Diego Rivera and controversial political interests, created a body of artwork that would stand the test of time.

In her diary, just days before her death, Kahlo penned her final entry stating, “I hope the exit is joyful—and I hope never to return.” Viva la Vida is a bright and vibrant celebration of life in both its simplicity of composition and complexity of emotional expression. It is not emblematic of the fear of death, nor is it hopelessly longing for the continuation of her own life. Rather, death, in the context Kahlo created, becomes a natural path that transcends the earthly plain and its burdens. This concept makes sense given the type of art Kahlo created, which generally portrayed visual elements that were intended to illustrate her physical frailties in a manner that illuminated her with spectacular color and light.

Just three years following the death of Kahlo, Diego Rivera died of complications from heart failure on November 24, 1957. During his final days, in tribute to Frida Kahlo, his wife, he painted a still life of cut watermelons simply called Las Sandías. This piece represents the indestructible bond Kahlo and Rivera shared in life and in death.

Diego’s rendering of this composition is quite visually different from Kahlo’s in the way that Rivera uses his chosen media to convey his emotional situation close to the time of his death. The watermelons are of a gray tone with a soft texture applied to the rind. The fruit’s flesh is subtly splotchy and appears as though it could be slimy and squishy to the touch. In the far bottom right corner, most representative of Rivera himself, is the shriveled up cut piece of watermelon, which is perhaps the most expressive aspect of this painting.

The visualization of the delicate changes that occur on the surfaces of slowly rotting fruit represents the progression of heart disease, as well as his age. Most importantly, however, it represents the lifeless nature of his existence following the death of his Kahlo. Despite the volatility of their relationship, he said of her death that “July 13, 1954 was the most tragic day of my life. I had lost my beloved Frida forever–Too late now I realized that the most wonderful part of my life had been my love for Frida.”

In terms of symbolism, the concept of the cut watermelons is, on the surface, rather ordinary, compared to the complicated themes of personal tragedy and sociopolitical turmoil the two generally conveyed within their artwork throughout the late 1920s and into the 1950s. However, the symbol of the watermelon acts as an agent of fragility, expressing the tenuous nature of life itself. This fact is evident in the manner in which both artists composed and executed their paintings.

Imagery of watermelons is also a significant point of cultural relevance in Mexican history and folk culture. It is commonly found in representations of the Dia de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) celebration and imagery generally relating to the honoring of human spirits. Thus, it is not at all surprising that both Kahlo and Rivera would use the symbol of the watermelon as a visual tool to articulate their thoughts and feelings.

The still lifes of cut watermelon, painted within three years of each other, would come to express the interplay between Kahlo and Rivera’s relationship with life, death, and eternal love. Kahlo’s Viva la Vida represents the appreciation she had for her ability to live and experience so many things throughout her 47 years of life, while Rivera’s Las Sandías represents the profound feelings of loss he experienced following the death of Kahlo.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————

Peighton L. Young is a writer, historian, and artist who is passionate about sharing her love of art, history, culture, and education with others. She received her Bachelor’s degree in Art History from Virginia Commonwealth University and is currently pursuing her Master’s in American History at the same institution. She is the creator of the blog exploringamericanhistory.