When the U.S. entered World War One in 1917, it is estimated that roughly 500,000 people who joined the United States armed services were immigrants. According to the National Park Service, this amounted to 18 percent of U.S. troops.

From the memoirs of Sergeant Alvin York from Tennessee, one of the most highly decorated Americans who served in the U.S. forces during World War One, we can learn more about life for this diverse collection of people. At first, he writes, he had been shocked by the fact that there were so many foreigners in his units: Italians, Poles, Irish, Greeks, and Mexicans. But, as he recollects, they soon became his buddies and he “learned to love them.”

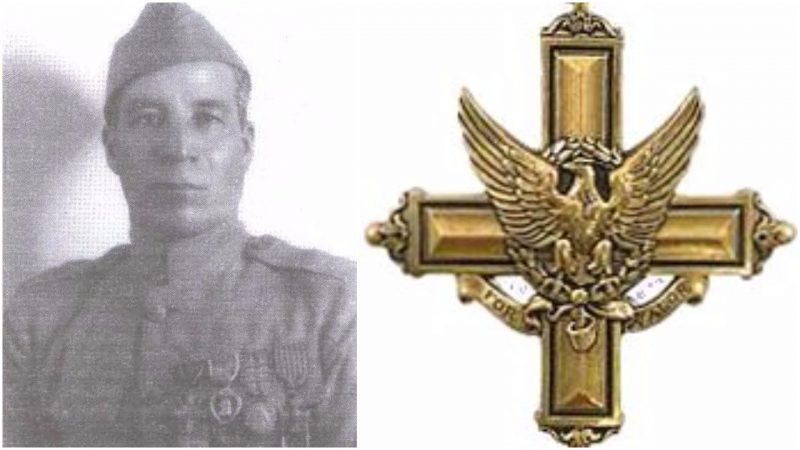

Many of these non-American soldiers went on to prove that their bravery and dedication to the cause was of the highest order. Among these, one of the most highly decorated was a Mexican-born illegal immigrant named Marcelino Serna, the first Mexican American to collect a Distinguished Service Cross.

He migrated from his home country of Mexico to El Paso, Texas, in 1915, when he was almost 20 years old. After working illegally for two years, Serna was eventually arrested by Federal officials concerning his status as a citizen. While he waited to find out if he was to be deported back to Mexico, Serna decided that he would show his desire to become a U.S. citizen by volunteering for the army.

He received less than a month of training in Kansas, after which he was deployed with his infantry unit to Europe, to fight in the French trenches. He was part of the 89th Infantry Division. Serna did not speak much English and upon his arrival, his superiors immediately noted he was Mexican. They offered to discharge him from service, but Serna politely declined.

On the battle lines, he proved his courage as a soldier several times, his actions speaking for themselves as to why he was worth all the decorations he later collected. In one confrontation with enemy soldiers, his squad was attacked and 12 fellows were killed. Injured himself, Serna nevertheless proceeded with the fight, going after the attackers and capturing eight adversaries.

Perhaps his most brilliant action followed shortly after this episode, when Serna discovered the position of an enemy sniper. He shot and wounded the enemy who dragged himself back to his trench, but Serna scouted after him and, in a solo encounter with the enemy soldiers on their “home terrain,” the Mexican managed to capture 24 soldiers and kill another 26.

As he led the defeated opponents to the base of the Allies, some of the fellows in his unit proposed that the captives needed to be executed, however, Serna, always knowing when to say no, refused to let this happen.

By the end of the war, Serna had suffered more wounds but luckily he had returned home alive. He was decorated with the Distinguished Service Cross, the highest American combat medal. His medal was presented to him by General John. J. Pershing, who was the commander-in-chief on behalf the American Expeditionary Forces. His unit also received the French Croix de Guerre with palm, which was presented by the supreme commander of the Allied Forces in Europe himself, the French Marshal Ferdinand Foch.

Serna later received another French medal as well as the Italian Croce al Merito di Guerra (War Merit Cross) in a ceremony hosted at Fort Bliss and attended by the Texas Governor of the day, William P. Hobby.

In the 1930s, following a petition carried out by another World War One veteran Cleofas Calleros, a Mexican who had lied about his citizenship in order to enter the U.S. army, Serna was additionally awarded the Purple Heart and the Allied Victory Medal. Many have questioned, though, why Marcelino Serna was never presented with the Congressional Medal of Honor, the most prestigious of all U.S. military decorations. According to Serna himself, part of the reason is that his superiors never recommended him due to his low rank and insufficient knowledge of the English language to obtain a rank promotion. For some critics, Serna’s case may have been a blunder based on prejudice because of his origins.

Still, the total number of medals which Serna received in the course of the war meant he returned as the most highly decorated Texan soldier. As soon as his army service was through in May 1919, Serna returned to live in El Paso. He obtained U.S. citizenship in 1924, by which time he had already settled down with his spouse Simona Jiménez, with whom he had six children.

Marcelino Serna passed away in El Paso in 1992, and full military combat honors followed his funeral at the Fort Bliss National Cemetery.