If music is food for the soul, then Carnegie Hall is without a doubt the finest restaurant where one could sit down to enjoy the very best cuisine of all. For more than a century, the crème de la crème of the music world had the opportunity to serve their best-prepared dishes to thousands and thousands of hungry souls in Midtown Manhattan.

Doyennes such as Rachmaninoff and Stravinsky amazed the world when they made their debuts at the beginning of the 20th century, and jazz crackerjacks such as Benny Goodman with his swing concert in 1938, as well as Duke Ellington, Dave Brubeck and Glenn Miller, among many, many others, made a name for themselves between those very walls in the years that followed. Similarly, Billie Holiday, Violetta Villas, Nina Simone, and Tina Turner achieved greatness after they made their voices heard in what is now a quintessential piece of the city’s cultural fabric and probably the most renowned concert hall in the world.

They all did what they were best at, hoping that one day what they were doing would eventually lead them to the hall in Manhattan and with that, to success. More often than not, the root to all achievement is a strong desire to succeed, and success is just a tiny fraction of time where that desire meets an opportunity. Many gifted individuals found theirs right here, in this hall in New York, the town where there is no Monday, Saturday or Sunday, where the vibe is great and art livelier than anywhere else. Their talent was nothing short of remarkable, so their success was inevitable, and Carnegie Hall proved to be just a realized dream and a stepping stone for them.

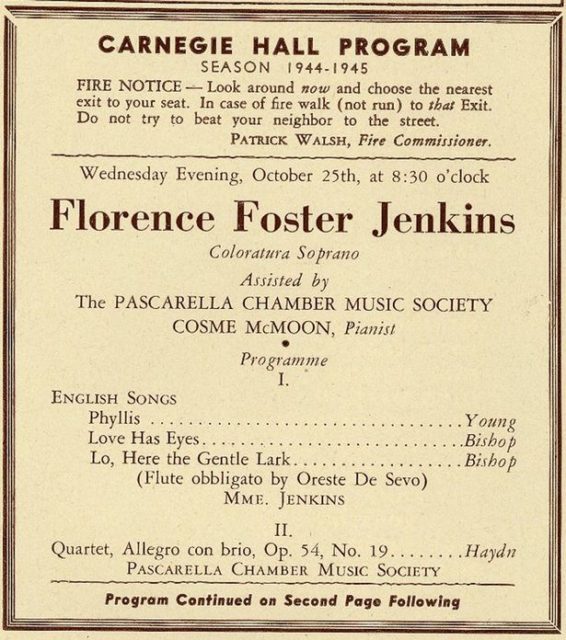

That being said, however, Mark Twain also wittily remarked that “all you need in this life is ignorance and confidence, and then success is inevitable.” On that note, a wealthy gal from New York with a strong desire to be the greatest opera singer that ever lived, on October 24, 1944, realized her dream and sang in the prestigious Carnegie Hall in front of a sold-out crowd, despite being “tone deaf” and having no talent for singing whatsoever.

Her name was Florence Foster Jenkins; she was a kind-hearted philanthropist who dreamed of living a life of singing. Her voice was awful and she sang terribly, but it was not because she wasn’t trained in music. As a child to a wealthy attorney, Jenkins had the desire as well as the means to lead a musical life so she learned to play the piano to the extent that she was quite good, and viewed as somewhat of a musical prodigy in her hometown in Pennsylvania. She was Wilkes-Barre’s “Little Miss Foster” until her fifteenth or sixteenth birthday, when she married a man twice her age and moved with him to Philadelphia.

Their marriage did not last long. She divorced him after three years when she discovered that her spouse, Dr. Frank Jenkins, had infected her with syphilis. Unfortunately, this incurable disease wasn’t the end of her misery. Her dreams to attend the Philadelphia Academy of Music and pursue a career as a professional piano player went down the drain when she injured her arm. She moved to New York with her mother at the beginning of the 20th century. Unable to play anymore, she used her father’s inheritance to start clubs for art enthusiasts and recital groups where others could play what their hearts desired and she would sing along.

Years passed and Florence built herself a devoted audience and a whole bunch of followers out of the guests that visited the clubs she ran, among which was the popular Verdi Club. She was no Luisa Tetrazzini by any means, as rare footage now found on youtube in which she takes on Mozart serves to prove, but still, as long as she was charitable and prepared to invest in others, and she was, her guests, who were mostly friends of hers or people looking for investment, were more than willing to clap along and applaud at her painful singing. Plus, she was kind to them, so why not.

Here, in 1909, she met St. Clair Bayfield, an established Shakespearean actor, yet a somewhat unsuccessful one at the time who found himself often times overlooked by directors. She was a singer who couldn’t sing, and he an actor who could no more act, and the two of them together were a match made in heaven. Despite having ears that probably ached as she sang, he fell for her strong passion and devotion to do what she loved, despite the fact that she clearly couldn’t do it. Jenkins aspired to sing professionally so he made sure that she did.

From what is known, he arranged opera classes for her and breathing exercises in order to improve her ability to carry a tune and correct her pitch. With time, Bayfield solely focused on Jenkins and her career and grew to be her manager for the rest of her life, making sure she would always perform in front of hand-picked audiences full of supporters and excluded from the outside world of harsh reviewers and music critiques. With time, she came to be a somewhat prominent figure in Manhattan and New York, a generous donor in the world of art, and a singer who was wrapped up in so much insincere praise and false admiration that she never came to realize she was singing badly.

Years went by when, in the 1940s, her life would take a turn as she fell into serious illness, most probably due to complications of the disease she acquired at a young age. Left untreated, syphilis began to take its toll. Her husband, who realized that time was ticking fast for his beloved, pulled every trick he had up his sleeve and arranged for her to sing as soon as possible in the most prestigious place in New York. Carnegie Hall was what she craved the most, and this was a loving man’s last present to a dying longtime partner.

What followed was an unprecedented “you have to hear how this lady sings” race to buy a ticket, as today’s Carnegie Hall museum director Gino Francesconi would say, stating that the hall was completely sold out almost instantly and weeks in advance. What she was not aware of was that they were buying tickets for a comedy show, and not to hear the voice of a great diva.

On October 24, 1944, ultimately every single person got what he or she expected. For while she gave a whole new meaning to the word practice, preparing like there was no tomorrow, which in her case was actually true. She just couldn’t sing, at all, despite all the efforts. The performance was horrendous as suspected and for Florence, it was the first time ever where she sang in front of a crowd not handpicked. She was sadly forced to face the reality afterward. As she read the subsequent reviews such as, “It takes courage and skill to be this bad,” which were actually written by the musical elite and not her friends, she found out for the first time what people truly thought about her voice and singing, probably realizing that she had been a laughing stock for quite a while, and this, of course, left her devastated.

She suffered a heart attack two days after that and passed away within a month at the age of 76. Her unusual story would have been lost forever if it wasn’t for Stephen Frears, who decided to make a movie and shed some light on the peculiar life of one of the “greatest contributors to the continuum of art and culture in New York City,” as Francesconi remarks, but a dreadful singer on the side. Frears hired none other than Meryl Streep to portray the so-called “Diva of Din” and her undying ambition to be a star.

The movie came out in August 2016 and revealed her last few months as she was preparing for the grand event, which proved to be her greatest lifetime achievement and all she ever wanted. So doing what you love, even if you do it badly, sometimes does pay off.

“Florence was a person who kept something we all have when we are children — when you can’t really do anything that well, but you hurl yourself into the imagining of it and take delight in the doing,” said Streep about the character she played, eventually earning her an Oscar nomination for Best Actress in a Leading Role at the Academy Awards.