Our society enjoys reading “rags to riches” stories of well-known business people, entrepreneurs and corporate executives, with explanations of their career path, seasoned with advice of “how to become a millionaire in one year,” “how to instantly elevate your career,” or “grab your opportunity and make it grow.” People might hope to learn that success is something obtainable after reading a few tips, the stories romanticizing the hardships and struggles of the established business leaders who came a long way before enjoying the fruits of their success.

One such person was Madam C. J. Walker, America’s first black millionaire and the first woman who became a self-made millionaire.

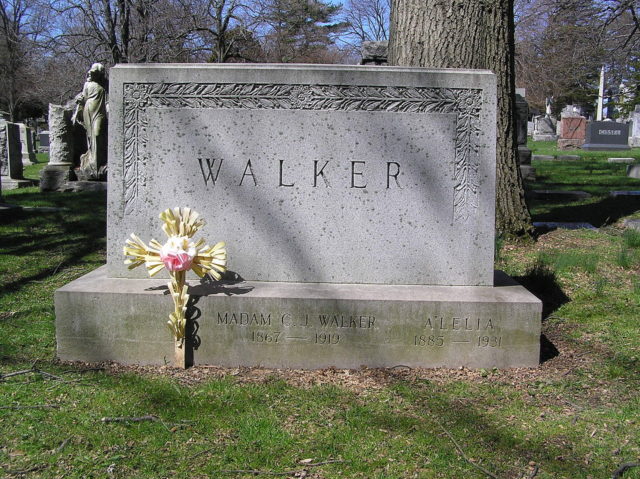

Madam C. J. Walker was born Sarah Breedlove in 1867, the first “free” child in a family of former slaves on a Louisiana cotton plantation. Orphaned at seven, Sarah was sent to live with her older sister, Louvinia, and her brother-in-law, with whom she moved to Mississippi in 1877.

There, Sarah picked cotton in the fields, working in an oppressive environment, and was often mistreated by her brother-in-law. In order to escape this unbearable situation, at the age of 14 she married Moses McWilliams and soon after gave birth to a daughter named A’Leila. Widowed at 20, Sarah moved to St. Louis with her daughter where she worked as a washerwoman, earning $1.50 per day. In the evening, when working hours were finished, Sarah attended night school. Obviously, nothing in her life came easily and her meteoric rise to business success arose out of hardship.

During the 1890s Sarah suffered a scalp disorder that resulted in immense hair loss. At the time, hair loss was a very common health problem, as most people were unable to bathe or frequently wash their hair due to having no access to indoor plumbing, central heating, and electricity. Bathing was a luxury and those who couldn’t afford it became targets of environmental hazards such as bacteria, pollution, and lice. Trying to improve her condition, Sarah began experimenting with various home remedies, combining different products that she consequently turned into homemade shampoos and hair treatments.

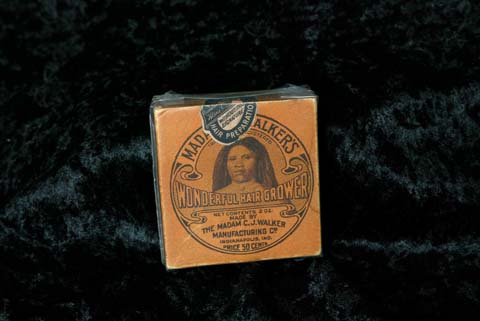

The product that prompted the launch of her unexpected career was the tonic she claimed to make her hair grow back “faster than it had ever fallen out.” With the help of her new husband, Charles J. Walker, a newspaper sales agent with much experience in the sphere of advertising, she promoted the “wonderful hair grower” in the black newspapers, along with other hair products for African-Americans that gave curly hair a “beautiful silky sheen.” Her husband also suggested naming the maker Madam C. J. Walker.

The launch of Sarah’s hair products began with door-to-door sales performed by her and her husband across the United States. Designed specifically for black women, Madam Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower and Madam Walker’s Vegetable Shampoo were a new, authentic cosmetic hit. In addition to every sale, Sarah educated women about hair and scalp treatments, demonstrating her “Walker Method,” which was her unique approach of using heated combs.

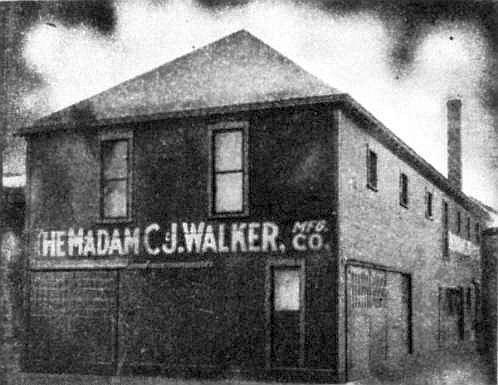

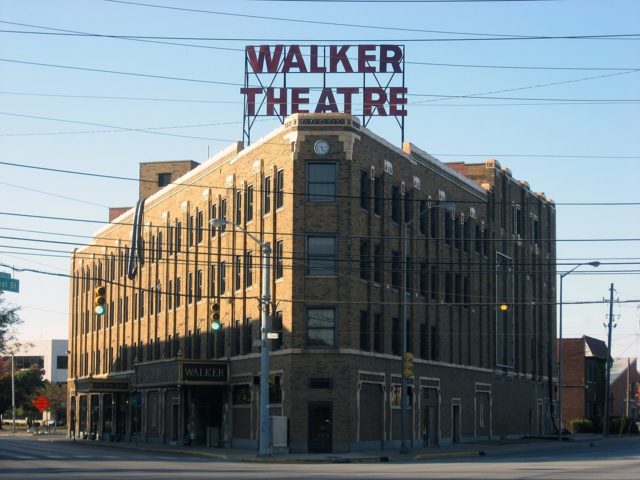

Business soon went through the roof as her products sold all across the States and could even be ordered by mail while Madam Walker was traveling. Profits continued to increase and in 1908 Walker opened a beauty school and a factory in Pittsburgh before she finally decided to settle her business in Indianapolis. The Madame C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company became so successful that it not only manufactured cosmetics but trained sales beauticians, known as the “Walker Agents,” ascending the company’s profits to a modern-day equivalent of a few million dollars. The beauty agents promoted Walker’s philosophy of, as Sarah had once stated, “cleanliness and loveliness.” In her “Hints to Agents” manual, she explained “Open your windows — air it well … Keep your teeth clean in order that your breath might be sweet … See that your fingernails are kept clean, as that is a mark of refinement.” Walker organized clubs and discussions for her representatives who recognized her educational and philanthropic ideas. Soon, she provided employment for hundreds of African-Americans as she internationally expanded her company to Cuba, Haiti, Panama, Costa Rica, and Jamaica, displaying a lucrative sales strategy and a talent for advertising.

Using the multi-level sales marketing system, she employed numerous agents and, simultaneously, built her fortune. Time magazine in 1998 described Walker as an entrepreneur who “unveiled the vast economic potential of an African-American economy, even one stifled and suffocating under Jim Crow segregation.”

By the time of her death at age 51, Walker proved herself to be a generous donator to scholarship funds, the NAACP, and campaigns against racist violence. She helped with the building of a black YMCA in Indianapolis and the restoration of Frederick Douglas’ home in Washington. At last, she found her place in the American elite business milieu, settling in a luxury mansion in the Westchester village of Irvington, a neighborhood in which the tycoons John D. Rockefeller and Jay Gould owned houses.

Finally, here’s a brief tip by Madame Walker regarding climbing up the social ladder. “I am a woman who came from the cotton fields of the South. From there I was promoted to the washtub. From there I was promoted to the cook kitchen. And from there I promoted myself into the business of manufacturing hair goods and preparations….I have built my own factory on my own ground.”