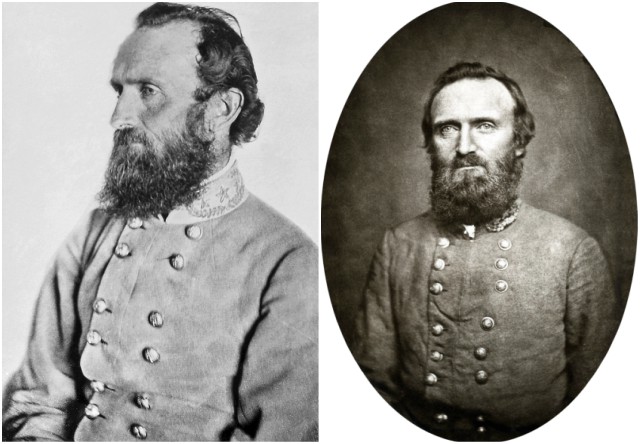

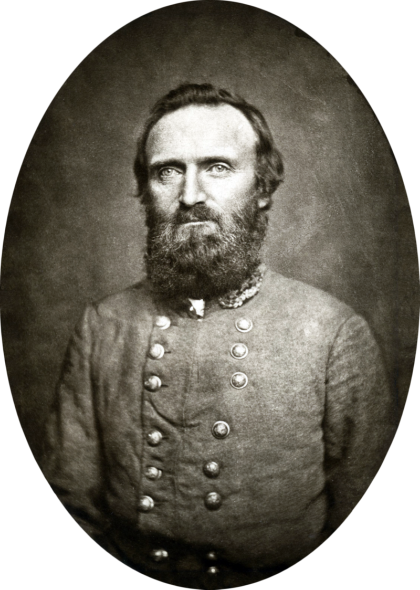

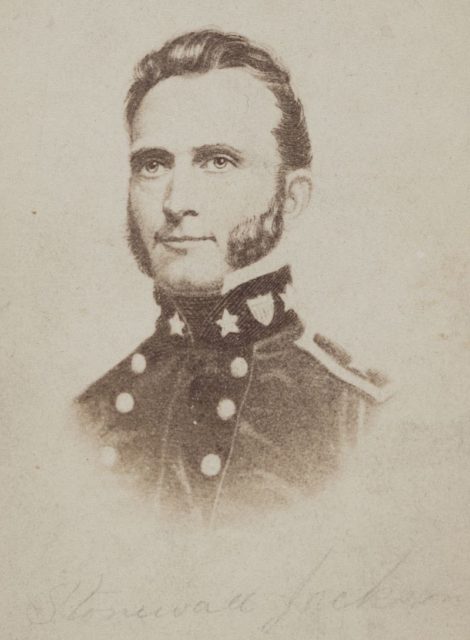

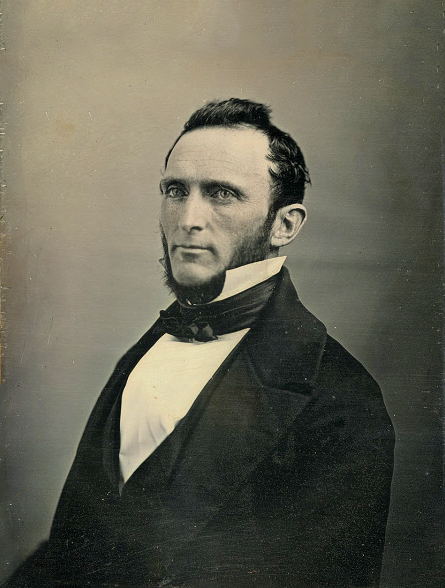

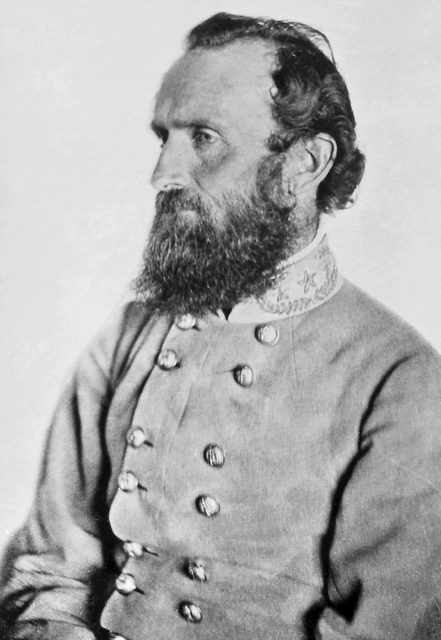

Thomas Jonathan Jackson, better known as Stonewall Jackson, was a legendary Confederate General during the American Civil War and one of the most accomplished tactical commanders in the history of the United States.

However, the story of Stonewall Jackson has more to it than it seems as he was more than just a successful Confederate General.

If we go a little deeper into history, we will discover that General Jackson is considered by many to be a civil-rights leader. In a period when, in the state of Virginia, teaching African-Americans to read and write was against the law, General Jackson broke this law every Sunday.

Born on January 21, 1824, in Clarksburg, Virginia, Stonewall Jackson was the third child of Jonathan Jackson and Julia Beckwith Neale. When he was only 2-years-old, tragedy struck his family, as typhoid fever killed both his father and sister. His mother remarried, but in 1831 she died due to complications during childbirth, so Jackson went to live with his father’s brothers.

He attended some of the local schools, but much of his education was self-taught. On one occasion, the future legend of the American Civil War made a deal with one of his uncles’ slaves to teach him how to read in exchange for pine knots. Just like he promised, he secretly taught the slave despite the fact that this was considered a crime at the time.

In 1842, Jackson enrolled in the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, and after four turbulent years, he managed to graduate from West Point. His next challenge was the Mexican-American War.

He joined the 1st U.S. Artillery Regiment and quickly earned a reputation for bravery and resilience. When the war ended in 1846, he was considered a war hero and was already promoted to the rank of brevet major, but the real hero was born when he returned home.

When he returned to civilian life in 1851, he started working as a professor of natural and experimental philosophy and an instructor of artillery at the Virginia Military Institute. He wasn’t among the most popular professors at the VMI; in fact, he was probably the least popular and was often ridiculed by his students.

However, this was not the case with the slaves in Lexington who respected him and considered him a hero of the African-American community in Lexington, and there was a good reason for that. At that time, according to Virginia law, it was illegal to teach African-Americans to read and write. However, Jackson believed that everyone deserved to be educated and decided to establish the Lexington Presbyterian Church Sunday School, where together with his wife, he taught African-American children to read and write.

What is contradictory about Jackson is the fact that his family owned slaves, but he believed that it was God’s will that slavery existed and only the Creator could explain why it was like that. He also believed that it was his mission to save their souls by teaching them the Old Testament history, The Ten Commandments, the Lord’s Prayer, and the Apostles’ Creed.

Dr. William Spottswood White described the relationship between Jackson and his Sunday afternoon students: “In their religious instruction, he succeeded wonderfully. His discipline was systematic and firm, but very kind. … His servants reverenced and loved him, as they would have done a brother or father. … He was emphatically the black man’s friend.” He addressed his students by name and they, in turn, referred to him affectionately as “Marse Major.”

Even after he’d left Lexington to join the Civil War, he never forgot his students and often sent them money so they could buy Bibles and hymnals. Many of his students from the Lexington Presbyterian Church Sunday School went on to become some of the most respected citizens of the United States, and thanks to General Jackson, a great number of them later became an integral part of American history.