It’s hard to imagine today but there once lived and breathed women who strongly believed that women did not have the right to vote or enjoy the same privileges of public life as men did. The question of why someone should want to deprive themselves of the right to vote, among other basic human rights, is certainly intriguing.

During the time of the suffragettes, women who were against women’s rights were called ”anti-suffragettes” or “anti-suffragists,” while others labeled them as “remonstrants,” “governmentalists,” or just plain “antis.”

At the beginning of the 20th century, the wave of American and British women known as “suffragettes” reached for the ballot box, paving the path to social and political justice. However, their efforts were unexpectedly hindered by the anti-suffragettes who emerged in opposition to their movement, diminishing their efforts on behalf of traditional values and social comfort.

Who were these women and why did they speak out against a woman’s right to vote?

The anti-suffragettes can be categorized as women who were in most cases well-educated, privileged, and earnest, and, for different reasons, sincerely believed that the state of a nation, and women themselves, would suffer if women achieved political equality with men.

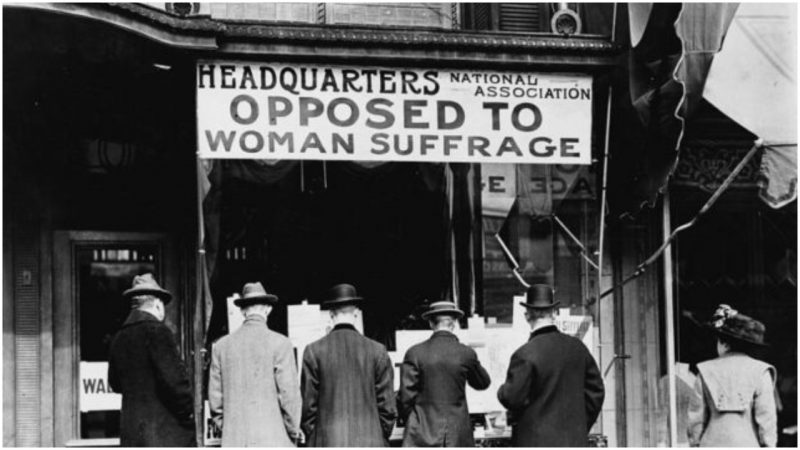

In 1911, the National Association Opposed to Women’s Suffrage (NAOWS) was founded. Its founder was Josephine Dodge, the leader of a movement that, surprisingly, provided day-care centers for working mothers. NAOWS actively organized events and campaigns, distributing publications and pamphlets.

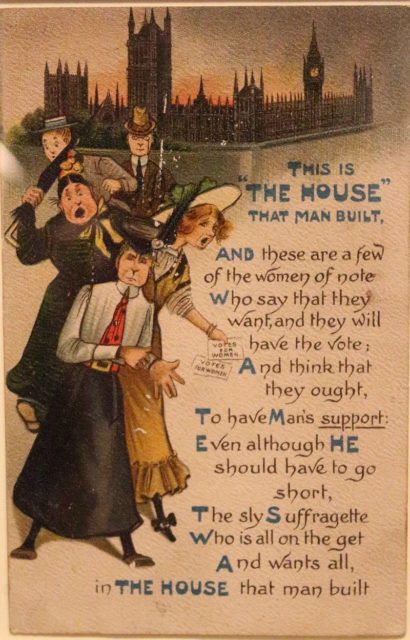

According to the history lecturer Susan Goodier, the movement coalesced around the idea that American and British societies required women and men to operate separately in the name of prosperity and the proper functioning of the nation; that is, domestic life was reserved for women, whereas public life was reserved for men. Women were considered peacekeepers, nurturers, and protectors of the home, and so, in alignment with the so-called inherent natural strength of their sex, it was expected that they’d stay away from the public realm, it being men only.

In 1884, The New York Times published an anti-suffrage petition that opposed the granting of voting rights to women, primarily in reaction to what the editors saw as the “the imposition of political duties upon women.” It explained that women were already burdened enough, having so many domestic tasks to contend with, that a possible participation in elections would increase their responsibilities further. The anti-suffragists argued that most women didn’t even want the right to vote as they never stayed up to date on politics. Some even argued that women lacked mental capacity or expertise regarding political issues. Often it was asserted that women would make voting cost more as they would double the size of the electorate.

Another rationalization was that in addition to domestic duties, such as caring for children, cleaning the home, and daily cooking of all meals, most women actively participated in activist pursuits and charities, community organizing, or grassroots advocacy anyway.

The leaders of the anti-suffragist campaign were generally elite ladies of high social status who themselves possessed political power. Corinne McConnaughy, a teacher of political science at the George Washington University, in her book The Woman Suffrage Movement in America: A Reassessment, says, “In short, they were women who were doing, comparatively, quite well under the existing system. They were generally urban, often the daughters and/or wives of well-to-do men of business, banking or politics. They were also quite likely to be involved in philanthropic or ‘reform’ work that hewed to traditional gender norms.” So, in short, granting the rights to vote would take away some of the power of these women, or The New York Times put it in 1894, “To give women the suffrage would only increase the ignorant vote and bring refined women into contact with an element that should not be brought into their lives.”

In the first decade of the 1900s, the anti-suffrage narrative came up against the numerous states that supported women’s right to vote. The rise of the suffragists gained momentum up until 1918-1920, when women’s suffrage was finally granted.

After their movement failed, most of the anti-suffragists called upon their civic responsibility and voted, and many of them said they did so proudly.