When we think of how World War Two came to an end, we recall the atomic bombs dropped on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. However, before the situation escalated to the point of the Allies commissioning a nuclear weapon, some devastating air raids were green-lighted.

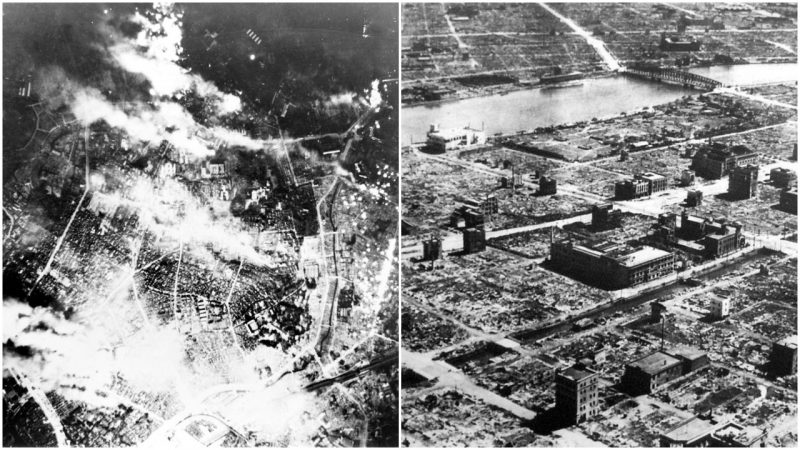

An air-raid conducted on the night of March 9-10, 1945, is regarded as the single deadliest air raid in the history of the war. It damaged a greater area and led to more deaths than either of the two nuclear bombings. Reportedly, over 1 million people had their homes destroyed during the Tokyo bombing that night, and the estimated number of civilian deaths is recorded as 100,000 people. Subsequently, the Japanese would dub this event the Night of the Black Snow.

The United States declared war on Japan the day after their surprise-attack bombing of Pearl Harbor–“a date which will live in infamy,” in the words of President Franklin Roosevelt. In the Pearl Harbor attack, 188 U.S. aircraft were destroyed, 2,403 Americans were killed, and 1,178 others were wounded. The very first air raid on Tokyo occurred as early as April 1942, but these initial raids were small scale.

In the spring of 1945, Germany was clearly headed for surrender, but Japan was resisting any talk of surrender and President Harry Truman faced the prospect of further heavy American casualties in the Pacific war. Once the long-range B-29 Superfortress bombers had been introduced into service in 1944, the U.S. Army had the capacity to conduct strategic bombings and operations in urban areas.

Bombing raids on Japan had been ongoing since the B-29s were first deployed to China in April 1944, and then to the Mariana Islands seven months later. The results were unsatisfactory, because even in daytime, precision bombing raids were hampered by cloudy weather and the strong winds of the jet stream. When command of the 20th Air Force came to General Curtis LeMay in January 1945, he immediately set about planning a new tactic. His first change was to switch from general purpose to incendiary bombs and fragmentation bombs. These were used from high altitude in February on Kobe and Tokyo. The next step, boosted by the fact that Japanese anti-aircraft batteries had proved less effective at the low altitude of 5,000 feet to 9,000 feet, was to launch a low-altitude incendiary attack.

And so on March 9, 1945, a total of 334 B-29 bombers took off for Operation Meetinghouse. Pathfinder aircraft went out first to mark the targets using napalm bombs, then the horde of B-29s flew in at an altitude of between 2,000 feet and 2,500 feet and proceeded to firebomb the city.

A great portion of the loads used 500-pound E-46 cluster bombs that would release napalm-carrying M-69 incendiary “bomblets.” The M-69s would go off in the first few seconds upon impact, and they most certainly ignited great jets of blazing napalm. M-47 incendiaries were one other type of bombs that were greatly used too, and these weighed 100 pounds. Jelled with gasoline, the M-47s also had white phosphorus bombs that ignited upon impact.

The fire defenses of Tokyo were eliminated in the first two hours of the raid as the attacking aircraft successfully unloaded their bomb deposits. The raid was performed strategically, having the first B-29s unloading their bombs in a vast X pattern concentrated in Tokyo’s densely populated working class districts nearby the city’s waterfronts.

The next rounds of bombings would add to the action by targeting the huge flaming X. This endless rain of bombs at first caused individual fires that shortly after would join all together in one unstoppable blaze that was further worsened by winds.

The result: an area of little less than 16 square miles of the city diminished under the fire, and 100,000 people lost their lives. A total of 282 out of the 334 B-29s at disposal for the action had made it successfully to their target. Another 27 bombers failed to survive the raid either because they were hit by air defenses or were caught in upward currents of the massive fires.

Air raids over Tokyo continued in the period afterward, and the death toll perhaps reached 200,000 civilian deaths alone. While the war in Europe was concluded with the Nazi Germany surrender May 7, 1945, the Japanese continually refused and ignored the Allies demands of unconditional surrender.

The Japanese finally did surrender, on August 15, 1945. It was six days after the second atomic bombing, of Nagasaki.