In 1921, the town of Greenwood, Oklahoma, a suburb of Tulsa, was notable for two main reasons: It was a vibrant, affluent community, and it was black. Taken together, these facts would prove its doom.

The area around Tulsa flourished in the early 1900s, thanks to an oil boom. Like every city in the United States at the time, Tulsa was strictly segregated. African Americans settled to the north of the city. Despite white hostility sanctioned by burgeoning Jim Crow laws, Greenwood residents created their own thriving and successful community of new houses, churches, grocery stores, movie theaters along with banks, restaurants, clothiers.

A man born a slave built a 54-room hotel. They reaped the benefits of a school system, which some of their white counterparts did not. Recognizing the value of education, teachers were highly respected and better compensated than other professionals. “Teachers lived in brick homes furnished with Louis XIV dining room sets, fine china, and Steinway pianos,” wrote James S. Hirsch in Riot and Remembrance: The Tulsa Race War and Its Legacy. It was the wealthiest black community in the United States.

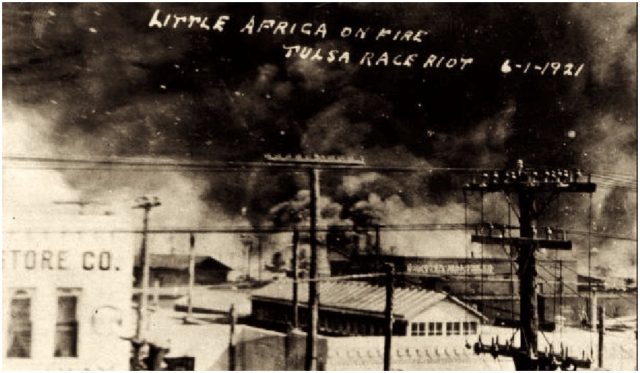

Some white people called it “Little Africa.” A New York writer described it as a “Black Wall Street.” Even though the relative wealth did not reach all Greenwood residents. Hirsch notes that “Black Wall Street hardly suggests the poverty, squalor, and neglect that were common outside Greenwood’s vibrant business district and a block or two of prime housing.”

“They had done everything that they were supposed to do in terms of the American dream,” explained Carol Anderson, Professor of African American Studies at Emory University, in a video series called The Hidden History of the Quest for Civil Rights. “You work hard, you save your money, you go to school, you buy property. And this is what they had done under horrific conditions.”

White resentment festered. The community’s prosperity would not survive. “That resentment in Tulsa was so intense,” Carol Anderson said. “It was just waiting for a spark in order to ignite it.”

The situation that sparked the community’s fiery demise was all too common in the era: a black teenager, a shoe-shine boy named Dick Rowland, and a white elevator-operator named Sarah Page. What happened exactly is lost to history, but allegedly the girl screamed. The next day the Tulsa Tribune ran a headline, “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in an Elevator.”

When Rowland was brought in by white police, a group of armed black World War I veterans gathered in front of the courthouse where he was being held, intending to protect the young man from lynching. White men gathered carrying guns and torches. By 10 p.m., the crowd had swelled to thousands. On both sides, the men were uneasy, tense, and edgy. According to a 2001 report by the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921, one of the white men, using the N word, asked a black veteran, “What are you going to do with that pistol?”

“I’m going to use it if I need to,” the black man replied.

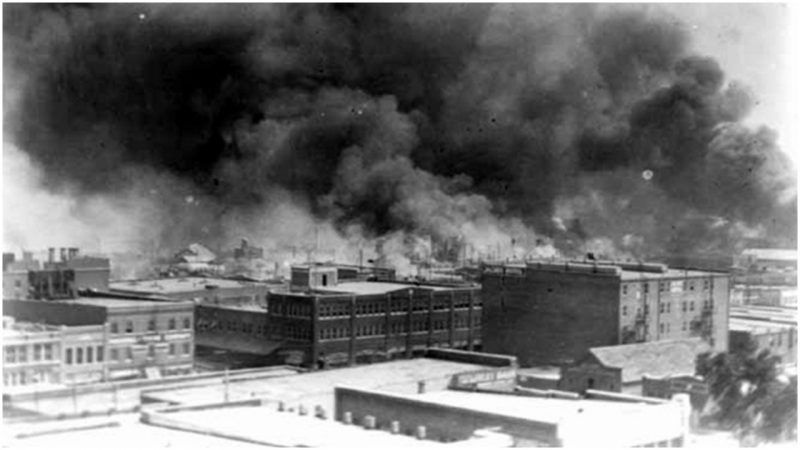

It was the excuse the mob was waiting for. Shots rang out, all hell broke loose. Black and white men ran down the street, shooting indiscriminately. Mob mentality took over, and all during that night and into the next day, black people were dragged behind cars, their homes, churches, schools, and businesses burned to the ground.

Planes flew overhead—some piloted by whites who dropped gasoline on the buildings below. The Tulsa police called on the National Guard and allowed the town to burn while they waited. When they arrived, they detained as many as 6,000 residents. Around 300 black people dead, 35 square blocks destroyed, and 9,000 left homeless, surviving in Red Cross tents through the harsh winter.

No white man was ever arrested or tried. Greenwood never recovered. A Klansman in control of the Tulsa Real Estate Exchange tried to enact regulations to turn the area into an industrial zone. Determined black attorneys fought the injunction, taking the case to the Oklahoma Supreme Court, which ruled in their favor. While some residents did indeed rebuild, Greenwood was never the thriving community it had been. In the 1970s, it was largely destroyed to make way for a highway.