The Swiss psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, and founder of analytical psychology, Carl Jung, was remarkable not only for the contributions he made in the field of psychiatry but also in a number of other disciplines like anthropology, archaeology, and literature.

He shaped key concepts such as individuation, central in his analytical psychology; archetypal phenomena; the collective unconscious; synchronicity; extraversion and introversion.

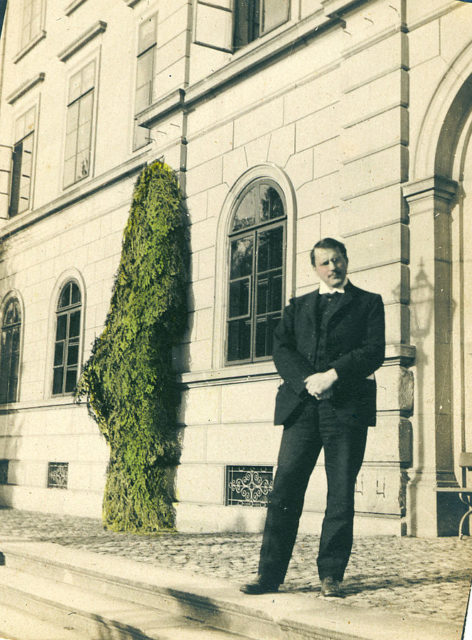

Jung quickly became a notable research scientist at the renowned psychiatric clinic Burghölzli, part of the University of Zürich. Working under Eugen Bleuler, an expert with a thorough understanding of mental illnesses, Jung was able to connect with Sigmund Freud – a connection that well deserves our attention.

Carl became first interested in psychiatry as a student reading a copy of Psychopathia Sexualis by Richard von Krafft-Ebing. He successfully completed his degree in 1900 and took an internship at Burghölzli. At one point, Bleuler asked him to write a review of Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams. That was an important contact he had with Freud’s work that was still forming at the beginning of the twentieth century.

By 1905, Jung became a senior doctor at the clinic and later on a lecturer at the medical faculty of the University of Zürich. As a science, psychology was just beginning to develop, and Jung was perceived as one of the new talents who had the capacity to take things up to the next level. Freud was also seeking new collaborators himself; somebody who would naturally extend his new “psycho-analysis.” Carl Jung seemed the perfect fit.

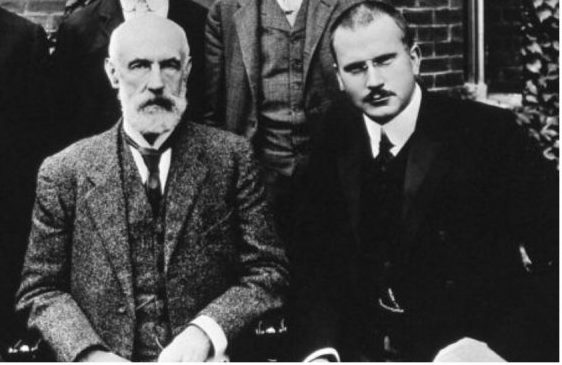

At age 30, Jung sent his Studies in Word Association from Vienna, to Sigmund Freud who was 50. After a lively correspondence, the two men met on March 3, 1907. Their first meeting had undoubtedly been an immersive one. The two of them talked for thirteen hours virtually without taking a break. Six months later, Freud sent a collection of his latest published essays to Jung, and that triggered a six-year intense collaboration and relationship.

The two scholars continually influenced each other and their work kept on growing. In 1909, both of them traveled to the States, accompanied by the Hungarian psychoanalyst Sándor Ferenczi. They attended an important conference at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, which gathered a number of exceptional psychiatrists, psychologists, and neurologists. More or less, the conference meant acceptance of psychoanalysis in North America. Jung returned to the States one more time during the following year, as he forged connections that welcomed his work and presence.

In 1910, the relationship between Jung and Freud was further crowned as Jung became Chairman for Life of the newly-established International Psychoanalytical Association. He took the position with Freud’s support, who would also call Carl “his adopted eldest son, his crown prince, and successor.” Things were really going well until 1912 when their relationship would quickly come to an end.

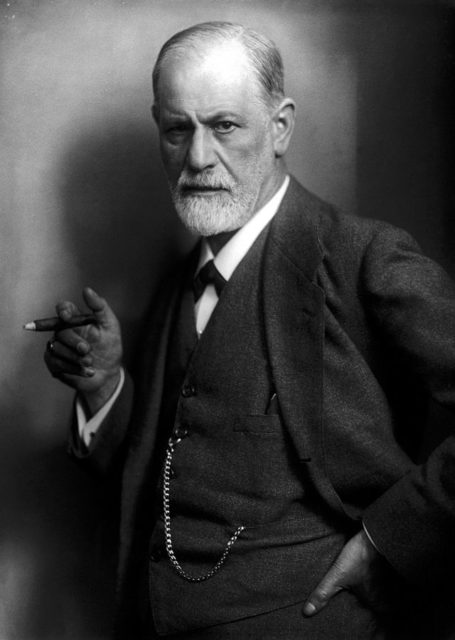

The first tensions between the respectable psychoanalysts occurred once Jung started his work on Wandlungen und Symbole der Libido (Psychology of the Unconscious). Each of them had a different understanding as to the nature of libido and religion.

For Freud, the personal development of the individual had to do everything with libido; for Jung, sexual development was not the crucial aspect. Instead, he focused on the collective unconscious, the part of the unconscious where he believed memories, ideas, and archetypal images were inherited from ancestors.

Unlike Freud, Jung argued that the libido is not the sole trait responsible for forming one’s personality. There were other factors he considered, and once the Wandlungen und Symbole der Libido (Psychology of the Unconscious) was published in 1912, the disagreements between the two culminated in separation. It was virtually a “break-up” that hugely affected their personal and professional relationship. Each of them considered that the other was incapable of admitting that might be wrong.

Jung resigned his chairman position at the International Psychoanalytical Association, and through 1913, he also suffered a period of “creative illness.” In the same time, Freud would also go through his own period of what he called neurasthenia and hysteria.

In between 1906 and 1913, Jung and Freud exchanged in total 360 igniting letters. They were first published in 1974 by Princeton University Press. The literary critic Lionel Trilling would write in The New York Times: “In no way does it disappoint the large expectation it has naturally aroused.”

Read another story from us: Fascinating audio recording & rare footage of Sigmund Freud

These 360 letters will remain an eternal reminder not only of the early developments of psychoanalysis but also of the intense relationship between the two geniuses which kicked-off after those first 13 hours of talking without a break.