President Calvin Coolidge gave her the nickname “America’s Best Girl” after she swam across the English Channel in 1926. In her day, Gertrude Ederle captured the public’s imagination in the same way as other athletic and patriotic heroes like slugger Babe Ruth and aviator Charles A. Lindbergh. She was overwhelmed when an estimated 2 million people showed up in the financial district for a ticker-tape parade on August 27 celebrating her accomplishment, chanting “Trudy! Trudy!” (Never mind that her family actually called her “Gertie.”) She sustained a career as a minor celebrity for about a decade before retreating into a quiet life of teaching deaf children how to swim.

Born in New York City on October 23, 1905, Gertrude Ederle learned to swim off the Jersey Shore, where her father, a butcher, had a summer cottage. She called herself a “water baby,” according to the New York Times, and said she was “happiest between the waves.” She suffered measles at age 5, which affected her hearing. Doctors told her swimming would make it worse, but she loved the sport too much to quit. She began competing in her early teens.

Ederle dropped out of high school to train with the Women’s Swimming Association, and by the early 1920s, she held 29 records. She swam in the Olympics in Paris in 1924, winning two bronze individual medals and a gold on a relay team. In 1925, back home in the United States, in her first event as a “professional” swimmer, she crossed from Lower Manhattan to Sandy Hook, New Jersey, in seven hours and eleven minutes, beating the previous record, set by a man.

But she had her eye on a bigger prize, an endurance challenge no woman had ever attempted: crossing the English Channel, which only five men had managed. She made her first attempt later that year, but had to stop when a crew member inadvertently touched her, means for instant disqualification. She was furious.

She returned to the Channel challenge the next summer. On August 6, 1926, Ederle dove into the water at Cape Gris-Nez on the French coast, wearing a two-piece bathing suit, cap, and goggles, and coated in lanolin to protect her from jellyfish and the cold. A mandatory tugboat chugged beside her as she stroked, carrying Ederle’s coach, her father, and her sister. Rough waves and powerful currents took her off course; the 21-mile swim stretched to 35 miles. Nevertheless, she persisted, as the modern feminist saying goes. In her head she timed her stroke to the lyrics of a popular song, “Let Me Call You Sweetheart.” Her crew members encouraged her by holding up signs that read “one wheel,” “two wheels,” in a nod to the red roadster she was promised if she accomplished the crossing, according to the New York Times.

At one point her father called, “Gertie, you must come out!” To which she replied: “What for?” Fourteen hours and 31 minutes later, she staggered onto the shore at Kingsdown, England, not only becoming the first woman to have made the crossing but also beating all the previous record, set by a man, by two hours. Remarkably, no one bettered her record until 1950. And she did get that red roadster.

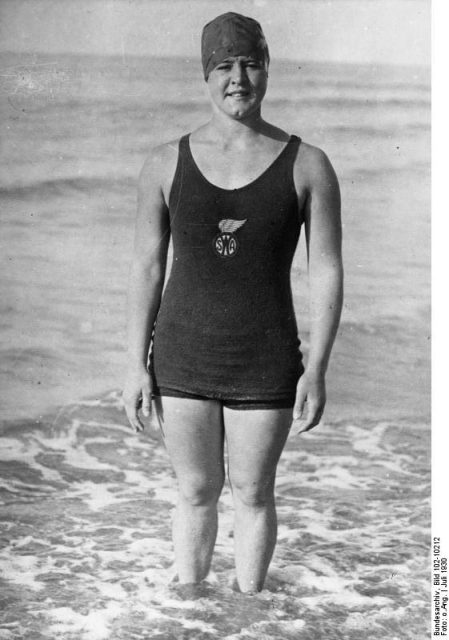

President Coolidge invited Ederle to the White House, where he said: “I am amazed that a woman of your small stature should be able to swim the English Channel.” A curious observation, since Ederle was hardly petite: at 5’6’’ she weighed 142 pounds and was “a strapping, broad-shouldered girl, big and plain and jolly,” as the New York Daily News reported. The press called her “Queen of the Waves.” Songs were written about her, marriage proposals offered. (She declined.)

In the following years, Ederle attempted to capitalize on her fame: she joined a vaudeville act, she made a film about her life, she gave motivational speeches. But she wasn’t comfortable in the spotlight, preferring the solitude of swimming. And her deafness was worsening, making her appearances in public an exhausting ordeal. She had what she would describe as a nervous breakdown. ”I finally got the shakes,” she told an interviewer years later, according to the New York Times. ”I was just a bundle of nerves. I had to quit the tour and I was stone deaf.” In 1933, she fell down stairs in her apartment building, injuring her back so badly she spent the next four years in a cast and was told she would never walk or swim again. She defied doctors however, making her last public appearance as a swimming celebrity in the 1939 World’s Fair.

In her later years, as Ederle’s hearing further deteriorated, she taught children how to swim at the Lexington School for the Deaf in New York. Though she did not herself know sign language, she empathized with the children and felt she could communicate with them through body language in the water. In 2013, a renovated pool and recreation center opened on West 60th Street, just blocks from where she had grown up. In her honor, it was renamed the Gertrude Ederle Swim Center.

Gertrude Ederle lived for many years with female companions in Flushing, Queens, and died in a nursing home in Wycoff, New Jersey, in 2003. She was 98.