Laura Ingalls Wilder was 65 years old in 1932 when she published Little House in the Big Woods, which introduced the world to a fictionalized version of her 4-year-old self. Despite the Depression, the book met with instant critical and commercial success.

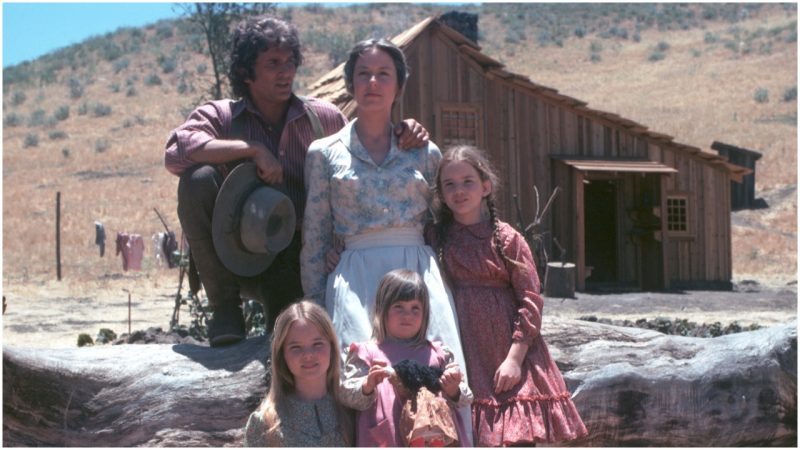

Little House was the first in a nine-book series that would go on to sell upward of 60 million copies worldwide in 33 languages. In the 1970s, it was adapted into a TV series, Little House on the Prairie, starring Michael Landon as the revered Pa and Melissa Gilbert as the plucky Laura, aka Half-Pint, which ran for nine seasons and widened the audience to a new generation of readers.

Two years ago, Gilbert delighted legions of devoted Little House fans by returning to the story as Caroline, or Ma, in a staged musical adaptation. Largely responsible for much frontier nostalgia, shaping the myth of the late 1880s Wild West, Little House is an undeniable and enduring classic.

But how much of the story came from the memory and imagination of a matronly farmer’s wife in her mid-60s, and how much of it was the work of her daughter, who happened to be a professional journalist, magazine writer, and editor?

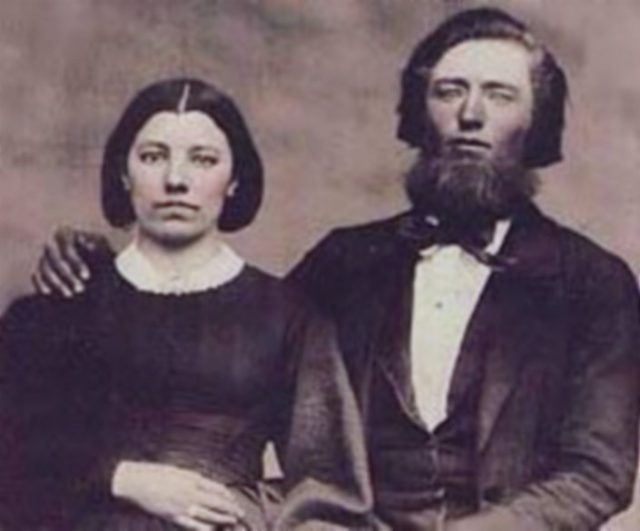

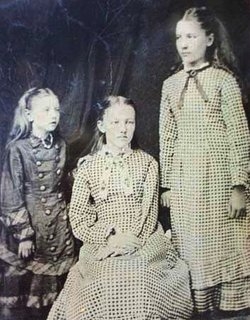

As everyone who’s read the series knows, Laura Ingalls, who was born in Wisconsin in 1867, moved mostly Westward as she grew up with her Ma and Pa, and her sisters, Mary, Carrie, and baby Grace, living in log cabins, sod dugouts, frame houses, and other improvised structures. Like most scrappy and resourceful frontiers people, they made their own food, clothing, and furniture, barely eking out a living but enjoying the warmth of a close-knit family. Inevitably, the novels sanitized the truth: a baby brother died in infancy, the family fled creditors, they nearly starved to death—more than once. When she was 15, Laura met Almanzo Wilder in South Dakota. They married when she was 18, and their only daughter, Rose, was born a year later.

For Laura, life was even harder with her new small family than it had been with her father’s. An infant died, their house burned down, they were so destitute Rose went to school barefoot, for which her classmates teased her mercilessly. They were malnourished, on which Rose blamed her life-long dental problems. Almanzo, who couldn’t live up to the standards set by Laura’s worshiped Pa, suffered a stroke, from which he never fully recovered.

Rose left as soon as she could. In 1915, she moved to California and became an assistant at a newspaper, where she learned to re-write prose to make it sing and to see the value of being re-written without protest. She got married and quickly divorced, never to remarry.

She wrote for newspapers and magazines, traveling to Paris, Russia, Berlin, and Armenia. She spoke several languages, smoked cigarettes, and counted among her friends the literati of the day. In what seems like obvious foreshadowing, she also ghost-wrote memoirs and celebrity biographies. Indeed, she was considered something of a tabloid sensationalist, annoying some of her subjects, including Henry Ford, future president Herbert Hoover, and Charlie Chaplin, who threatened to sue. She also suffered from periodic depression so dark she felt suicidal. In fits of grandiosity, she built her parents a large house, which they didn’t want, and bought them a Buick, which Almanzo drove into a tree.

While Laura never left the family’s struggling farm, she pursued her own humble literary career of sorts, writing a column for The Missouri Ruralist under the name “Mrs. A.J. Wilder,” about housekeeping, country life, and cooking, to supplement their income.

When the stock market crash of 1929 wiped out the savings of all the Wilders, Laura sat down to write the story of her life, through the gauzy haze of nostalgia. She wrote long-hand in pencil in a large notebook. In a shrewd move, she passed along the pages to her daughter, the professional journalist, to type up. Rose couldn’t resist editing, enhancing, and embellishing the text as she transcribed. Rose added so much drama that sometimes Laura protested she didn’t recognize her prose.

“A good bit of the detail that I add to your copy is for pure sensory effect,” Rose explained in a letter, according to a 2009 New Yorker story.

The first draft of the story, Pioneer Girl, was turned down by several agents and publishers. On the advice of one, mother and daughter revised and recast the story to target “juveniles,” as the children’s market was called in the day. The book then met instant success, and they continued their partnership, often through the mail, which extended through the subsequent eight novels. Mother knew how to make cheese, fashion a door, frame a house, dig a well. Daughter knew how to add drama to the story. In her new biography Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder, Caroline Fraser writes, “Wilder’s writing was both uniquely her own and a product of collaboration with her daughter.”

“I have written you the whys of the story as I wrote it,” Laura told Rose in a letter, “but you know your judgment is better than mine, so what you decide is the one that stands.”

Paula Hill Smith, who edited The Pioneer Girl: The Annotated Autobiography of Laura Ingalls Wilder, told the New York Times in 2015 that the relationship between mother-writer and daughter-editor was “complicated.” “In much of the correspondence, we have this mostly warm and affectionate relationship, but Rose rails against her mother in her journal. And very early on it’s clear there was a great deal of rivalry and pain.”

The Wilders were a long-lived family. Almanzo died in 1949, at 92; Laura in 1957, at 90. In the 1950s, Rose became a Libertarian and is considered one of the founders of the American movement. She continued to write, but none of her publications achieved the lasting acclaim of the work she did with her mother. Rose died in 1968, at eighty-one.