Though he was one of the most influential independent producers of his time, Thomas Ince is today better known for how he died than how he lived. And like any good drama coming out of Hollywood, the story of his death is full of high-powered characters, conflicting accounts, and scandalous mystery involving two of the era’s most influential megastars, William Randolph Hearst and Charlie Chaplin.

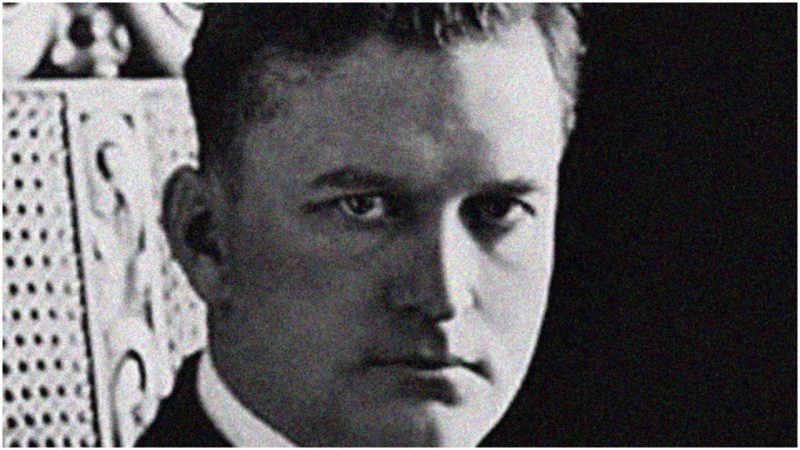

Thomas Ince was born into show business in 1880: His parents were actors, as were his sister and two brothers. He appeared on stage with his family at age 6, made his Broadway debut at 15, and later formed a Vaudeville act, which failed. He married an actress, Elinor (Nell) Kershaw, with whom he had three children. In the 1910s, Ince met the legendary filmmaker D.W. Griffith, who gave the young man his first production jobs. Inspired by his experience behind the camera and infected by an enthusiasm for Westerns, Ince moved his young family to California to set up his own studio.

Even for the day, Ince’s studio was impressive, an expansive 460-acre parcel in Santa Ynez Canyon on which he built a multitude of sets, including the expected saloons and boarding houses but also mansions and even a Japanese village. Later the area would cover an astonishing 20,000 acres, according to the Sony Pictures Museum, and came to be known as “Inceville.” By the time of his early death, Ince was responsible for the production of more than 800 films and was known as the Father of Westerns. His attention to every detail was legendary.

“He was so proficient at every aspect of filmmaking that even films he didn’t direct have the Ince-print, because he exercised such tight control over his scripts and edited so mercilessly that he could delegate direction to others and still get what he wanted,” the film preservationist David Shepard said in The American Film Heritage. “His influence far outlived him.”

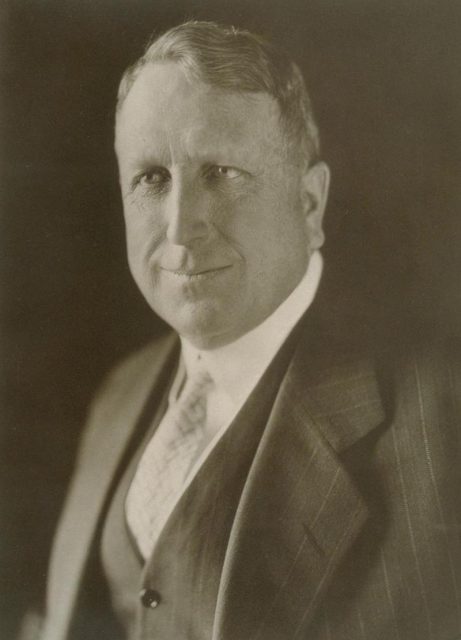

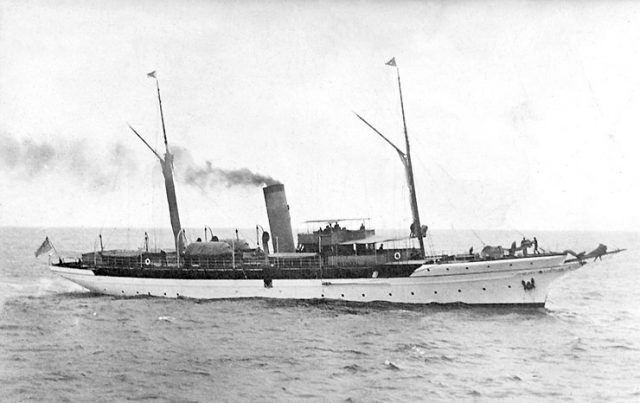

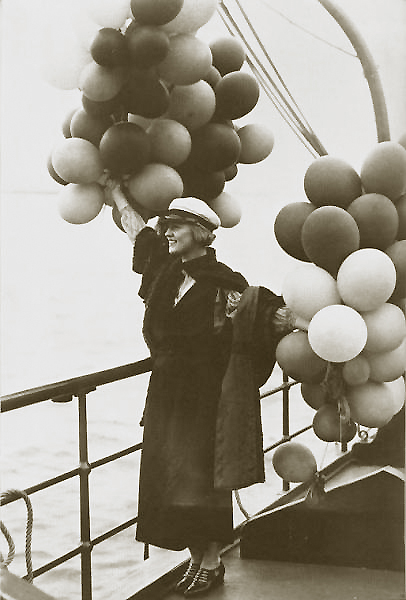

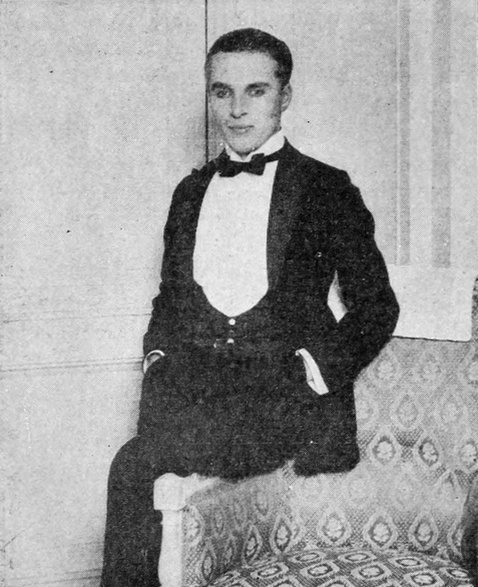

On the occasion of Ince’s 42nd birthday, in 1924, William Randolph Hearst invited the producer for a weekend excursion on his yacht to celebrate and also to hammer out details of a negotiation that would give Hearst access to Ince’s studio, and Ince a much-needed infusion of cash. Guests on the opulent 280-foot Oneida included stars, writers, managers, choreographers, and at least one doctor, among other Hollywood glitterati. Also on board was silent film star Charlie Chaplin—who was in the middle of shooting the extravagantly expensive The Gold Rush—as was Hearst’s mistress at the time, the silent film star Marion Davies, and a fledgling gossip queen, Louella Parsons. Ince was actually late to the party, having missed the November 15 launch, and joined the floating celebration on November 16.

A lavish dinner was thrown to mark Ince’s 42nd birthday, but the guest of honor retired with the terrible stomach cramps that mark acute indigestion, perhaps brought on by eating salted almonds and drinking champagne, both of which were ill-advised for a man with ulcers. Ince later left the boat with a doctor in Del Mar and summoned his wife, Nell, his own physician, and his son, who joined him to travel back to his home in Los Angeles, where he died three days later. Dr. Ida Cowan Glasgow signed his death certificate, citing heart failure as the cause.

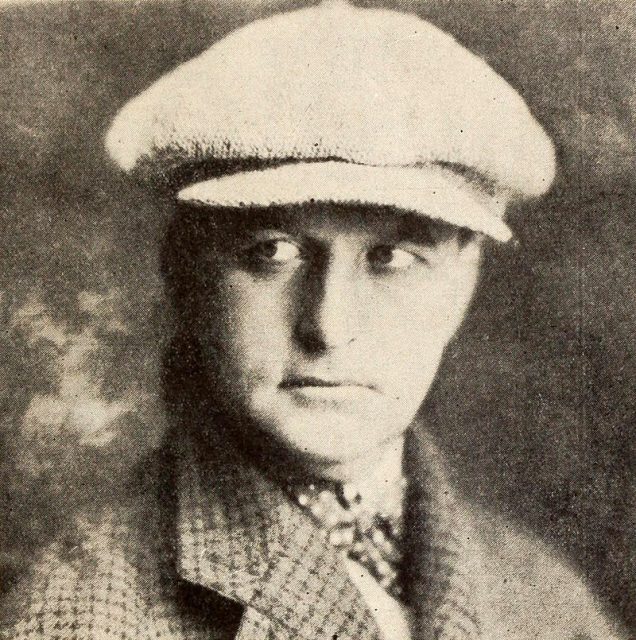

Ince was dead at age 42. Quickly rumors circulated that Hearst had shot Ince in a jealous fit of anger—though not at the producer but at Chaplin, whom Hearst suspected was having inappropriate relations with his beloved mistress, Davies. In this whispered version of the events, Hearst stormed around the yacht late at night seeking out Chaplin, stumbled across Ince, and shot him in a case of mistaken identity.

One of Chaplin’s servants allegedly saw Ince bleeding from a head wound. Some even suggested that Ince had himself made a pass at Davies, enraging Hearst. When Hearst later expanded the syndication of Louella Parsons’s columns in his media empire, wags noted that this was evidence of “hush money,” that she agreed not to report on the murder in exchange for her own gain. Some sources reported that the Los Angeles Times ran a headline that was quickly retracted: “Movie Producer Shot on Hearst Yacht!”

Likely it was the glittering cast of characters not to mention his relatively young age that perpetuated the mystery surrounding Ince’s death. Heart’s granddaughter Patricia Hearst—who’d gained her own notoriety through her kidnapping and subsequent bank robberies—became intrigued with the story and wrote a novel (with coauthor Cordelia Frances Biddle), Murder at San Simeon, in which she portrays Chaplin and Davies as lovers, and a jealous and angry Hearst accidentally shooting Ince. The scandal was revisited by Peter Bogdanovich in the 2001 movie The Cat’s Meow, in which he heightens the drama by suggesting the star Margaret Livingston was Ince’s mistress, that Ince was in dire financial straits, and that Chaplin had impregnated a 16-year-old girl. In the movie Cary Elwes stars as Ince, Edward Herrman as Hearst, Kirsten Dunst as Marion Davies, and an inspired Eddie Izzard as Charlie Chaplin.

The biography Thomas Ince: Hollywood’s Independent Pioneer dispels these theories as myths. Ince had been suffering from both ulcers and heart troubles, according to biographer Brian Teves, but had been keeping his failing health a secret.

The persistence of the rumors frustrated Ince’s wife, Nell, who died in 1971. “Do you think I would have done nothing if I even suspected that my husband had been victim of foul play on anyone’s part?” she said, as recounted by Hollywood journalist Adela Rogers St. Johns in her 1970 autobiography The Honeycomb. Rogers also looked into the rumors of Ince’s flirtation with Marion Davies, who scoffed at the idea that he would risk Hearst’s wrath. Davies said: “Why would [Ince] take such a million-to-one chance?”

Though his death may be more salacious, Thomas Ince’s lifetime of achievements is remembered in Los Angeles—he has a star on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame.