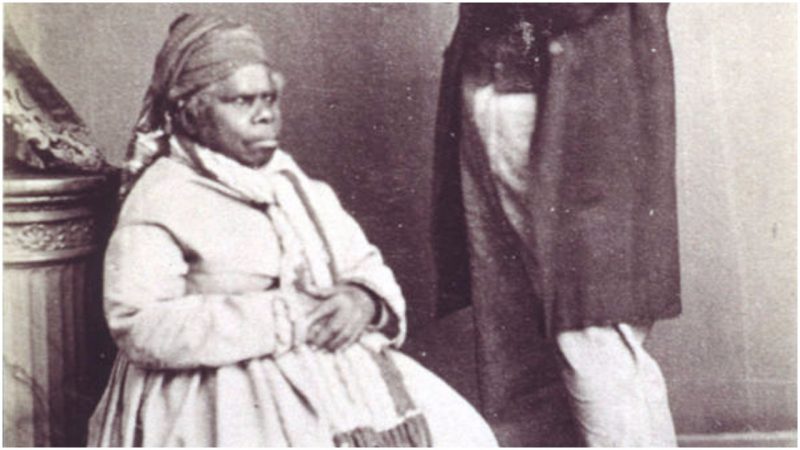

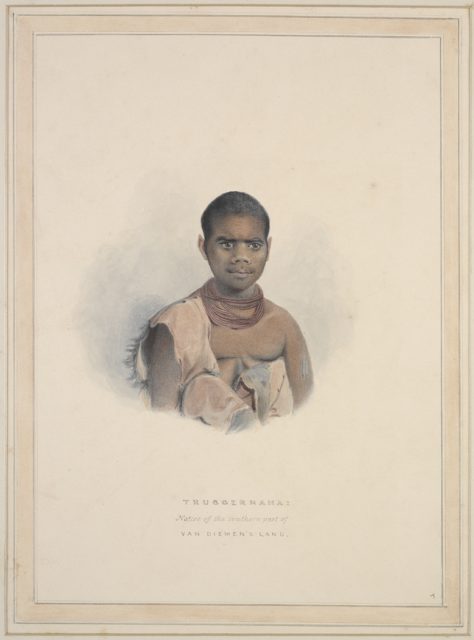

Life became very hard for the Aboriginal people of Australia when the Europeans invaded. One of the best known of the Tasmanian Aboriginal women from the colonial era, Truganini, was born on Bruny Island, just off Tasmania, little more than nine years after the British settlement of the mainland, around 1812.

At first living a traditional life, she spent her time learning to be part of her tribe, foraging for food, and doing all the things that made up aboriginal daily life. In time, the colonial settlements grew, and their influence across the land of Australia became decidedly intrusive to the native inhabitants.

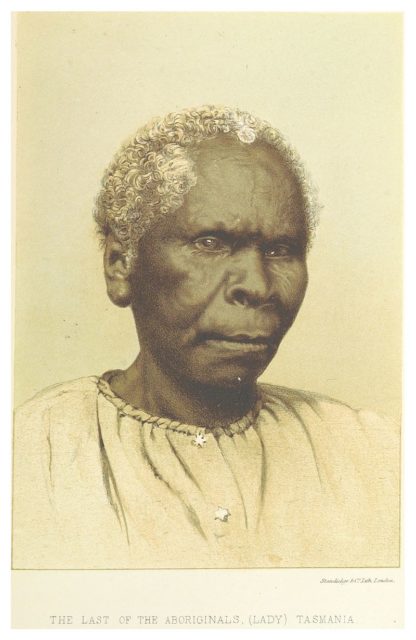

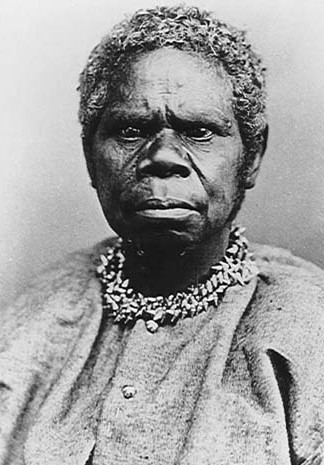

The aborigines of Tasmania were a short people with low body fat, skin-colored from black to a reddish brown, and tightly curled hair. It is estimated that they had arrived in Tasmania 35,000 years earlier when the land bridge between Tasmania and Australia was still in place.

They are thought to have become isolated for at least 10,000 years. They were a hunter-gatherer society, but there is very little else known about them other than fragments of information from English documents.

In 1803, a British convict settlement was built on the island. These convicts were brutal and began shooting and slaughtering the native inhabitants. The colonial government and scholars of the white world had decided that the Aboriginals weren’t really people. Not a single European was ever punished for the harm they did and the campaign of terror that was directed towards these Aboriginals was known as the Black War; from 1803 to 1830, the population of the natives on the island went from five thousand to just seventy-five.

Truganini didn’t escape any of the violence in her homeland. She lost her sister, mother, uncle, and fiancée to the violent attacks, involving not only the convicts but sailors, soldiers, sealers, and wood cutters. She herself was beaten and raped. In 1829, she was detained and placed in the custody of Augustus Robinson, who was capturing all the independently living natives. It is known that she remained under the supervision of colonial officers for the rest of her life. For 20 years, she was imprisoned on Flinders Island and then another 17 years at the Oyster Cove camp near Hobart.

In 1836, the artist Benjamin Law made a lifelike bust of her. By 1854 there were only 20 or fewer Aboriginals from Tasmania left. Many had died from European diseases that their bodies had no defense against. In 1873, Truganini, the sole survivor from Oyster Cove, was then moved to Hobart.

Scientists tried to obtain the aboriginal bodies for examination as it had been realized that the Tasmanian Aboriginals were different from those inhabiting the mainland. Truganini made a plea that when she died, her body be given a respectful burial. She feared that her remains would be desecrated in scientific inquiry and didn’t want her remains on display in a museum.

Sadly, after she died, her pleas were ignored, and her remains were put on display in the Hobart Museum until 1947. Public and Indigenous protests demanded that her body be returned, but they were removed from public view and locked in the Museum storage.

It took a hundred years after her death before the Palawa people, the modern Tasmanian Aboriginals, were able to reclaim her remains.

Finally, these were cremated and scattered close to her homeland, where she was able to rest in peace.