An omnipresent image of Japanese culture is that of the samurai, the “all-masculine” warrior who will decapitate an enemy in cold blood, or who will commit seppuku if he is to keep the honor of his name.

When thinking of Japanese women from history, a common image might be that of the geisha, the woman represented as gentle as a flower, always nicely dressed, making tiny steps forward, sometimes even looking so fragile it’s as if she were sick. When it’s springtime, the Japanese woman is walking down the lane beneath the cherry trees and perhaps having an ice cream.

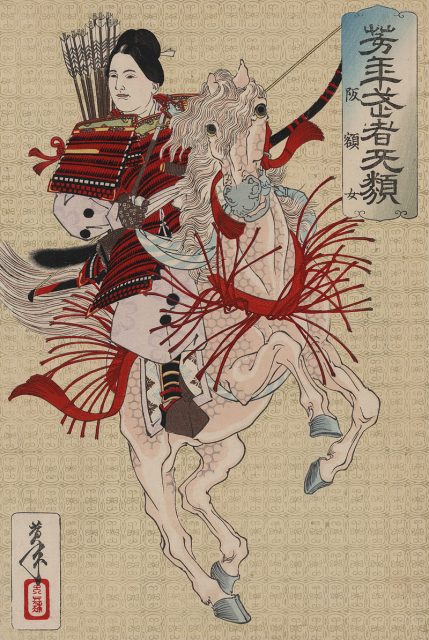

However, there are still women from Japanese history who can help deconstruct these stereotypical gender representations, one great example being that of the onna bugeisha, who by all means had nothing to do with a demure geisha. The onna bugeisha was, as the term virtually translates to, a woman warrior. They did exist, and some of them had an excellent talent with the sword, as much as, if not more than their male counterparts had.

Figures of famous Japanese women warriors can be traced far back in the timeline, to around 200 AD, raising the name of Empress Jingū, although she seems to be more of a product of ancient Japanese lore. According to some legends, she wore a set of divine jewels which bestowed upon her the power to control the tides of the sea. Helped by the gems, the empress had supposedly reached the Korean peninsula, invading the land in a campaign where not a single drop of blood was shed.

She supposedly invaded the Koreas following the death of her husband, and while carrying their son in her womb. Furthermore, according to legend, the baby had remained inside the empress for some three years, giving her the time to complete her mission in Korea and come back home to Japan. Her son was named Ōjin, and his figure is later revered among the Japanese as a deity of war and called Hachiman.

It is hard to prove the actual existence of an Empress Jingū, though it is still considered that around 200 AD, there was a thriving matriarchal society in the western parts of the Japanese islands.

Unlike the empress, the figure of the onna bugeisha is far from just a myth or legend, nor is it most accurate to claim that they were “female samurai.” The latter designation belonged to any woman raised in a family of samurai, regardless of whether or not they learned to use swords and go into battle as men within the family did.

In the old days, the female samurai was supposedly expected to keep an eye on the family income, take care of the finances, as well as to fit in the traditional female role of taking care of the household. The one difference was that they were also trained to fight an intruder if somebody happened to trespass on the family property when no men were around the house.

In contrast with the women samurai, the onna bugeisha were trained to protect entire villages and communities, not only the family property, primarily if there was a lack of “manpower.” When everything was well in place, these women remained in the household, also fulfilling the usual roles that women had in the home.

If for instance, a samurai had no son to pass down his knowledge to and instead a daughter, the father reserved the right to train his daughters as full-time onna bugeisha.

Japanese keep ancient archery tradition alive

Although not very often, it sometimes happened that the onna bugeisha indeed behaved like a samurai. They had the strength to fight with two swords in their hands, and they were also enlisted to serve in the army of a daimyo, side by side with a vast majority of male samurais. In these cases, they wore the attire and the hairstyles commonly worn by the men of the army. An example of such an onna-bugeisha is Tomoe Gozen, though numerous sources state that she was more of a legend than a real person from history.

Gozen had supposedly fought in the Genpei War, a confrontation between two rival clans of Japan, the events of which had unfolded somewhere in the latter part of the 12th century. During the battles, she earned a reputation as a fearless warrior, who would after that, become a symbol of a female heroine in traditional Japanese culture. Some of her deeds included leading an army of no more than 300 samurais in a battle against an army of 2,000. Allegedly, she was among the last survivors, and she managed to decapitate a prominent fighter from the adversary clan.

Whether she really lived or was just part of the lore is probably a question that will never be answered with 100 percent accuracy, but still, there are more names on the list, figures who are more than well-documented across historical accounts. Such would be Hangaku Gozen, Hojo Masako, and Nakano Takeko, the last of whom was one of the most authentic of all women warriors, at one point leading an army of women against the Imperial Japanese Army.

Accounts tell that she was a woman of exceptional intelligence who had mastered the art of fighting with the traditional Japanese sword known as naginata. When on the battlefield, Nakano Takeko had been noted for her fierce attacks, taking the lives of her adversaries in stunning movements. Her name pops up in more recent periods of Japanese history, following the 17th-century revolution in training women fighters.

By this period, it is known that the political climate in Japan had radically changed, and many more women than in the previous centuries had received training in martial arts and combat. Takeko was one of the best and therefore she was also chosen to take the lead as a commander of the women army of onna-bugeisha fighters. When she was tragically shot in the chest during a battle in 1868, she had reportedly requested her sister Nakano Yuko to save her honors and decapitate her so that nobody from the enemy could claim her remains as a trophy.

Her sister respected her wishes. Her head was buried under a pine tree in the boundaries of the Aizu Bangemachi temple and there is a monument raised there to honor her name. Takeko belongs to the last generation of woman fighters from Japanese history.