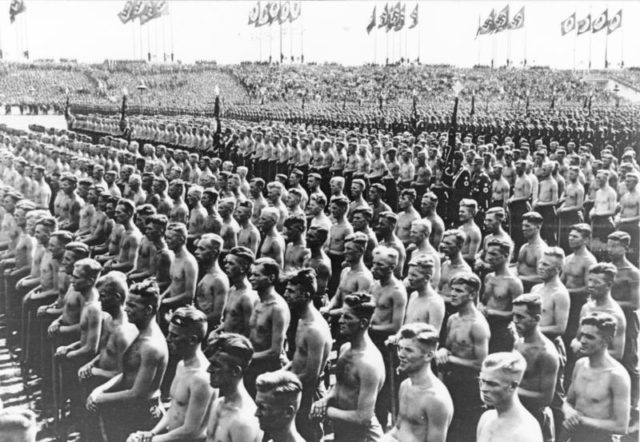

Once the Nazi party seized power in Germany in 1933, its members quickly infiltrated each segment of society. Hitler had risen to lead the party through his fiery speeches full of seeming conviction that he could resolve all of Germany’s problems. As the party grew and took tighter control of the country, he was able to put on more grandious demonstrations of the strength if the Nazi party and support for its ideology.

The cathedral of light was mostly an aesthetic feature that added to the grandeur of the Nazi Party, but its effect was certainly an effective way to showcase the impressive force of the movement.

The cathedral of light’s creator was architect Albert Speer, who was specifically commissioned by Adolf Hitler to construct a stadium in Nuremberg that would serve as a venue for annual rallies. The stadium could not be completed in time for the 1933 rally, so to improvise, Speer employed more than 130 anti-aircraft searchlights to point skyward encircling the assembly area. The result was, indeed, a cathedral of lights.

Each searchlight was be positioned 40 feet from the next, which generated a series of vertical bars of light surrounding the audience. The achieved effect was brilliant, both from inside and outside the arena.

The Lichtdom, as the name would become in German, was widely regarded as Speer’s greatest work of all. More than 300,000 participants gathered at the Zeppelinfield venue.

The searchlights used for the Lichtdom were borrowed from the Luftwaffe, the aerial-warfare branch of the German forces. Initially, their use raised concerns from the Luftwaffe‘s commander, Herman Göring, as the searchlights took up much of the nation’s strategic stockpile.

However, Hitler suggested that their usage in such a way would serve an important purpose, allegedly saying, “If we use them in such large numbers for a thing like this, other countries will think we’re swimming in searchlights.”

The searchlights were supposed to be a temporary solution until the stadium was finished, but their impact was so impressive that their use was repeated for subsequent Nary-party rallies at the Zeppelinfield. A similar effect with lights was even created for the closing ceremony of the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin, games that were followed by numerous scandals as Nazi sympathizers used the publicity of the event to show off their ideology.

The Flak Searchlights used for these shows were a design of the 1930s; they used 59-inch diameter parabolic glass reflectors and had an output of 990 million candelas. Each was attached to its own 24 kilo-watt generator for power through long cables, producing a 200 amp current that sent the pillars of light reaching up into the night to an altitude of between 2.5 and 3.1 miles.

Speer would describe the effect as follows: “The feeling was of a vast room, with the beams serving as mighty pillars of infinitely light outer walls.” The British ambassador to Germany at that time, Sir Nevile Henderson, would compare the effect to that of a cathedral of ice.

The cathedral of light was documented in the Nazi propaganda film Festliches Nürnberg, a 21-minute long film released in 1937. The piece chronicles the Nazi rallies in Nuremberg of 1936 and 1937, but it does not feature any translation of the commentary that it has.

The film revolves around the outpouring of adoration for the Führer, as other propaganda did in those days, with a number of scenes showing marching SS men and Wehrmacht soldiers, the Navy, as well as airplanes aloft. But probably the most awe-inspiring feature shown in the propaganda film is the cathedral of light.