All across the ancient world, domed structures can be found, some of them dating all the way to 3000 years BC. From the Iberian peninsula to the islands of Greece, the Gulf of Levantes and Asia Minor, the ancient Mediterranean cultures shared similar buildings that were most likely used as burial grounds for kings and other notable figures.

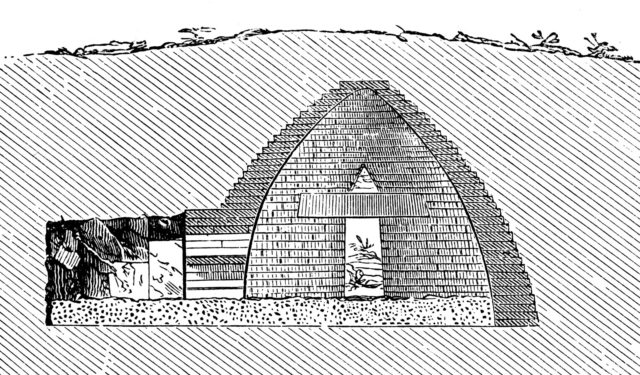

Constructed in a shape resembling a beehive, the tholos tombs (tholos being the Greek word for a domed tomb) represent some of the most important relics of the Late Bronze Age. The structures are built underground, with an entrance made of stone pillars.

The entrance led to the cut in the slope of a hillside and into the burial chamber, which was set two-thirds below ground level with the top of the dome protruding above ground. The final touch was to cover the dome with earth and let time form the tomb into a small hill with a stone entrance.

The tombs are similar in concept to the earlier Mycenaean chamber tombs―both consisted of a chamber, a doorway and an entrance passage. The main difference was that the chamber tombs were rock-cut, while the tholos was built and reinforced by the superposition of successively smaller rings of mudbricks or, more often, stones.

The careful placement of these elements guaranteed that the dome would last throughout the ages, and it is incredible how the structures have managed to survive centuries of natural disasters, wars, and tomb raiding.

Tholi are most typically found in the areas inhabited by Ancient Greek tribes and civilizations, such as the Mycenae on the Greek mainland and Minoans in the island of Crete, but they can also be found in today’s Spain, Iraq, and Syria. The tombs are also typical of other cultures that were in direct contact with Hellenic kingdoms, such as Thrace, located in today’s Bulgaria.

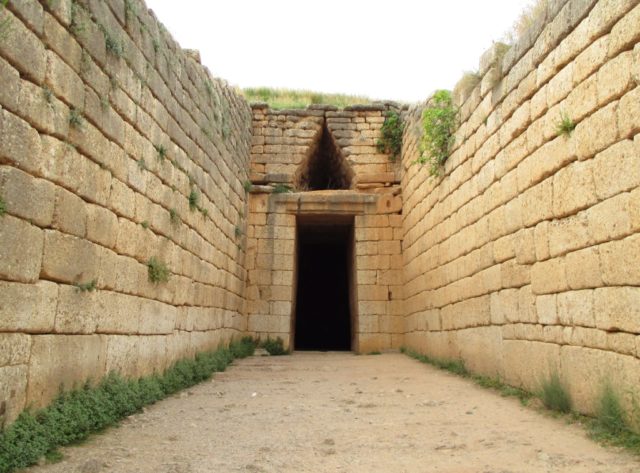

The most famous and perhaps the best preserved is located on the Panagitsa Hill in Greece. The place was once the heartland of Mycenaean civilization and it’s believed this is where the legendary King Atreus was buried.

Atreus, the father of Agamemnon, the famous Greek king who conquered Troy, was allegedly buried here somewhere between 1350 and 1250 BC, but scholars are unable to agree on whether this was indeed his tomb, or perhaps his glorious treasury.

Some consider the beehive tomb hosts the remains of his son, Agamemnon, while others argue that the tomb (or treasury) belongs to neither of them, as it is believed that both of the rulers of Mycenae Greece lived long after the tomb was constructed.

No physical remains were found at the site, most probably due to extensive looting which has plagued the locality since the late antiquity and throughout the modern age.

Another significant tholos, also related to the ancient rulers who brought Troy to its knees, is the tomb of Clytemnestra, the wife of Agamemnon, who, as the legend goes, murdered him after his return from conquest.

After 1500 BC, the beehive tombs became more common and replaced the older style because they offered a more stable and, most importantly, an easier to create solution. Through this shift, we witness the development of building technology in ancient cultures.

The burial chamber often housed more than one person, together with everyday objects like pottery. These were intended to represent the wealth of the deceased and to serve him, or her, in the afterlife. Among the most important discoveries of these grave goods are the two gold “Vapheio cups” on which marvelous scenes of bull taming are illustrated.

Other representations of wealth often came in the form of various decorations, expensive materials or exquisite craftsmanship.

The treasury (or tomb) of Atreus was decorated with famous stone brought from quarries more than 60 miles away in the province of Lacedaemon, or Lapis Lacedaemonius, as it was known throughout the Greco-Roman world. This extremely rare and expensive volcanic rock was found in various colors ranging from dark green to red and yellow.

Apart from the beehive tombs on the Greek peninsula and its numerous islands that served as burial crypts, examples found in the Middle East suggest that the beehive-like structures were used for storage of food, housing, or religious rituals.

Domed tombs of similar designs, created in various different periods, have been found in today’s Oman and even as far as Somalia.

In Spain, Portugal, and southern France, similar burial traditions can be found dating back to the Chalcolithic period, 3000 BC, and are most often related to the Los Millares pre-historic culture of southern Spain.

On the island of Sardinia, the autochthon Nuragic civilization, which occupied the Mediterranean isle in the period between the 18th century BC to 2nd century AD, used to build tholos-styled necropolis structures which served as burial grounds for up to 30,000 people.

Apparently, the burial rites and traditions were very similar in various civilizations of the Bronze Age, even though most of these cultures never had any known contact with each other.

Cultural similarities between different peoples, all of womh inhabited the Mediterranean basin in the ancient times, give us insight into a world long gone―a world upon which our world was built.