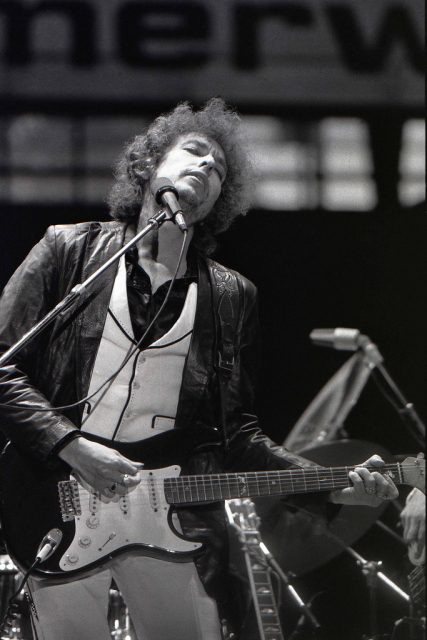

Enigmatic and cantankerous, counterculture icon and Nobel laureate Bob Dylan is a man of mysterious contradictions. The restless roots rocker has traveled the globe performing for five decades in front of adulatory audiences—even as his style evolved from folk and blues to rock and rockabilly—reaping the considerable rewards of fame. But as much as he stands in the spotlight, he also loathes it. A fierce guardian of his privacy, he rarely grants interviews and refused to show up to an awards ceremony to accept his controversial 2016 Nobel Prize for Literature.

Unsurprisingly for a man of his stature, Dylan has had many romantic entanglements over the years. Some were well known, like his affair with singer Joan Baez in the 1960s and his marriage to Sara Lownds, with whom he had four children.

Others were secret: He managed to keep his six-year marriage to Carolyn Dennis, and their daughter together, out of the public eye until well after they were divorced and the girl grown up. There were doubtless many other women along the way, but Dylan doesn’t appreciate conjecture. Indeed, when Factory Girl, a fictionalized biopic of Andy Warhol’s original It Girl, Edie Sedgwick, suggested that the skinny socialite had had an affair with Dylan, the moody rocker hit back hard: threatening to sue.

A daughter of wealthy Californian ranchers and descendant of East Coast elites, Edie was raised with a healthy sense of independence and superiority that were undermined by her battles with mental illness and eating disorders. In her twenties, she moved to Boston, where her family had deep roots, began studying art, and partied with her fellow upper-crust elite. But the stuffy scene bored her, and she moved to New York City, into an extravagant family-owned Park Avenue apartment.

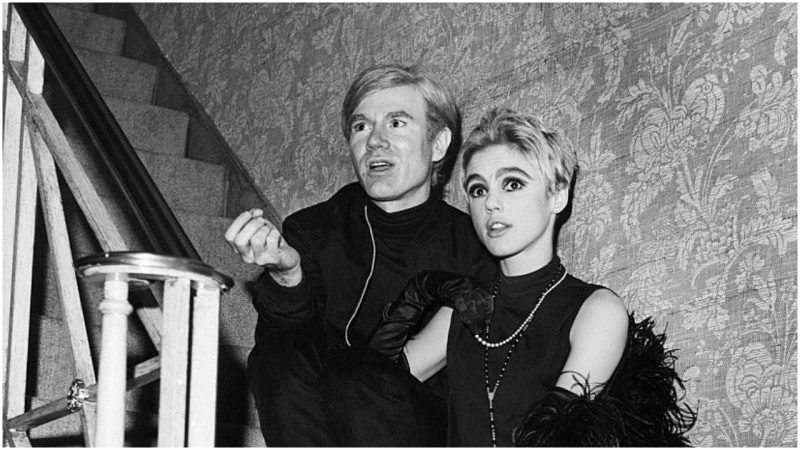

Soon Sedgwick met the man of the moment at a birthday party for the playwright Tennessee Williams. Andy Warhol had established himself as the King of Pop, had shown his now iconic soup can and Marilyn Monroe silkscreens, and gathered around him other fab-loving glitterati in his famous downtown studio the Factory. Musicians, artists, and other assorted sycophants hung out by day and partied at night; Warhol dubbed them the Superstars and cast them in his dubious films.

In Sedgwick, Warhol found his perfect muse: She had the kind of inherited wealth and aristocratic mannerisms that the former ad man from gritty Pittsburgh craved. They became a couple of sorts, though not the consummated variety. He wanted to be her more than with her. She reciprocated by cutting her hair short and dying it white-blond like his. The Velvet Underground, Lou Reed’s first band, which Warhol nominally “managed,” wrote a song about her, “Femme Fatale.” Sedgwick starred in ten of Warhol’s underground films, allowing him to mock her in the aptly titled Poor Little Rich Girl. Her look defined the era—black tights, leopard-print coats, chandelier earrings; skinny legs and shoulders, kohl-encircled eyes. Often she was under the influence of that era’s popular recreational drugs. More than once she fell asleep while smoking cigarettes, once setting her apartment on fire and badly burning herself.

Sedgwick’s last film with Warhol, Lupe, began with his chilling and prescient directive, according to Vanity Fair: “ I want something where Edie commits suicide at the end.”

As quickly as they had fallen for each other, Sedgwick and Warhol’s relationship turned sour. At the end of 1965, she became infatuated with a different kind of man, a scruffy, earthy, gruff, politically astute singer-songwriter, none other than Bob Dylan. Warhol was said to be devastated by her “betrayal.”

The Sedgwick-Dylan relationship didn’t last long and how far it went is lost to history. He had just come off his public affair with Joan Baez, and had secretly already wed Sara Lownds. Two songs on his 1966 album Blonde on Blonde were said to be written about Sedgwick: “Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat” and “Just Like a Woman.” A photo of a blond woman on the album sleeve may be Sedgwick, though Dylan denies that.

Sedgwick fell apart after her split with her famous flames. She moved back and forth between California and New York. She became institutionalized in a mental hospital, where she met and married a fellow patient. She died of a drug overdose in 1971, at age 28.

The movie Factory Girl lays all this out with Sienna Miller as Sedgwick, a spot-on Guy Pearce as Andy Warhol, and Hayden Christensen as a folk singer called Billy Quinn whose inattentions contribute to Sedgwick’s suicide. Re-cut and released in late 2006, Factory Girl was not a commercial or critical success, nor did it dissuade Dylan’s legions of fans from admiring him, though Miller was praised for her portrayal of the wispy WASP.