Only three horses in the history of the United States Armed Forces had the privilege of being given a military funeral with full honors. The first of them, named Comanche, was reportedly the sole survivor of the battle of Little Bighorn, also called Custer’s Last Stand.

The other two horses, Black Jack and Sergeant Reckless, deserve a story of their own, but for now, we are going to focus on the steed that started this tradition of respect for the noble animal companions in battle.

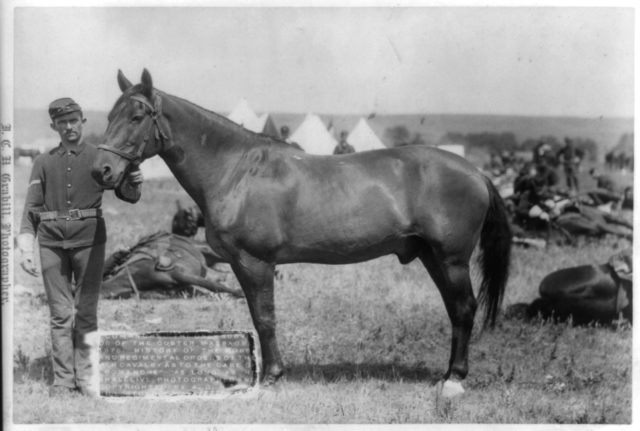

A mixed breed, Comanche was bought by the U.S. Army in 1868 for $90 in St. Louis and was sent to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. He was in the service of Captain Myles Keogh, a professional soldier of Irish descent who achieved considerable glory during the American Civil War.

Together with Comanche, Captain Keogh was stationed on the Western frontier, where the pair faced the Native American tribes of the Wild West–the Comanches, to be more precise, after whom the horse bears his name.

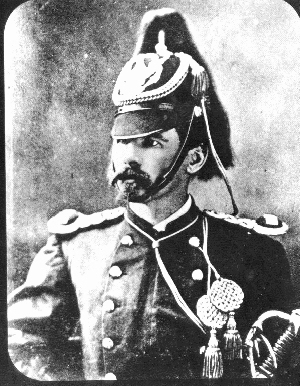

Myles Keogh was a colorful character, just like his horse, for he participated in various skirmishes in Italy before coming to the U.S. to assist the Union Army in 1862. After the war, he was stationed in Ft. Riley in northeast Kansas with the 7th Cavalry Company, under the command of George Armstrong Custer.

Like the legendary Bucephalus, the horse ridden by Alexander the Great, Comanche was famous for being capable of enduring wounds and fatigue, as well as being of fighting spirit. This was a truly noble beast, set to carry a fierce warrior like Captain Keogh.

During one of his first battles, Comanche was wounded in the hindquarters by an arrow but continued to carry his master through the fight. Even though the horse would be wounded many more times, he always exhibited unshakable tenacity.

Since Keogh respected his enemy, despite the fact that he both feared and despised the unconventional warfare waged by the Comanches, he decided to name his horse after the tribe.

The name stuck and highlighted the horse among hundreds of other steeds that carried their cavalrymen across the wild prairie.

He soon became respected among the troops as a reliable companion in the heat of battle. After many rough days on the frontier, Comanche was known throughout the 7th Cavalry.

In 1874, the tensions between the U.S. government and the Native Americans of the Plains tribe were growing, and sporadic conflicts were taking casualties on both sides. In 1876, the conflict reached its boiling point.

At Little Bighorn, a huge battle occurred―one that would enter the chronicles of warfare as a bloody defeat of the U.S. Army. Faced with a combined force of Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho, the 7th Cavalry Regiment was completely annihilated.

Comanche was found after the battle, badly wounded and barely standing, and in the rubble of dead bodies was his former rider, Captain Myles Keogh.

Even though Comanche is often referred to as the only survivor of the battle-turned-bloodbath, it isn’t entirely true. There were no human survivors on the American side, but there were other horses that were taken by the Native Americans.

Evan S. Connell, a historian on the subject of Custer’s Last Stand, as the battle of Little Bighorn was dubbed among the Americans, claims that several other heavily wounded horses were found in the aftermath of the battle, but only Comanche was given medical attention. Aside from the horses, one of the regimental dogs, a yellow bulldog, was also among the survivors.

Nevertheless, Comanche was given the honorary title, which attributed to his status of being the most famous horse in the Army. He was nursed in Fort Lincoln, North Dakota, where he regained health and strength. Comanche had been shot seven times but managed to survive.

In 1878, the warhorse was retired. Under the orders of Colonel Samuel D. Sturgis, Comanche received the following privileges in his retirement, which also serve as a testimony of his engagement in the Battle of Little Bighorn:

(1.) The horse known as ‘Comanche,’ being the only living representative of the bloody tragedy of the Little Big Horn, June 25th, 1876, his kind treatment and comfort shall be a matter of special pride and solicitude on the part of every member of the Seventh Cavalry to the end that his life be preserved to the utmost limit. Wounded and scarred as he is, his very existence speaks in terms more eloquent than words, of the desperate struggle against overwhelming numbers of the hopeless conflict and the heroic manner in which all went down on that fatal day.

(2.) The commanding officer of Company I will see that a special and comfortable stable is fitted up for him, and he will not be ridden by any person whatsoever, under any circumstances, nor will he be put to any kind of work.

(3.) Hereafter, upon all occasions of a ceremony of mounted regimental formation, ‘Comanche,’ saddled, bridled, and draped in mourning, and led by a mounted trooper of Company I, will be paraded with the regiment.

In 1879, Comanche was transferred to Fort Meade, and after that to Fort Riley, where he spent his last days. He was given the honorary title of a “Second Commanding Officer” of the 7th Cavalry and was even “interviewed” for the daily papers when his official keeper, John Rivers, who was an old battle comrade of Myles Keogh, told his story in order to save “Comanche’s reputation” by answering the questions.

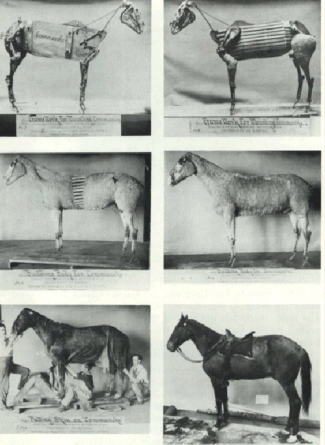

After years of excellent treatment and service as a ceremonial horse, Comanche died of a gastrointestinal disease in 1891, believed to be aged 29.

After his death, the horse’s remains were not buried, although a ceremony was held with the highest military honors. Instead, his body was taxidermied and exhibited at the Natural History Museum, which is part of the University of Kansas, where it remains to this day.