If a time machine could have engineered a meeting between Al Capone and Steve Rubell, the Prohibition-era Mafioso gangster would have given the 1970s disco impresario a tip: “Don’t mess with the IRS. The Feds don’t think you’re funny.” Indeed, both men who operated with open contempt for the law wound up behind bars not for their numerous practically public criminal activities, but for that most prosaic of reasons: tax evasion.

It is hard to imagine it today in New York City’s Times Square, which is basically a cleaned-up family-friendly walkable open-air mall of America. But back in the 1970s, the area was starkly different: a seedy, squalid, and dangerous neighborhood of porn shops, drug fronts, and loitering low-lifes.

It was against this backdrop that a young local entrepreneur named Steve Rubell, along with his college fraternity brother Ian Schrager, opened the most famous, glamorous, and decadent party palace of the era in a 1927 opera house-turned-sound stage: Studio 54. Dark and full of alcoves, the theater had a main dance floor, and mezzanine, balcony, and basement for private parties. For two and a half years, Studio 54 was an era-defining den of dancing, partying, and A-list iniquity, a Hieronymus Bosch painting come to depraved life. Everyone wanted in.

In bell-bottom jeans, low-cut satin dresses, and fringed jackets, the clubgoers clustered on the sidewalk behind a velvet rope outside 254 West 54th street, hoping Rubell, standing on a stepstool, would select them for a chance to mingle with an incredible list of that era’s naughty glitterati.

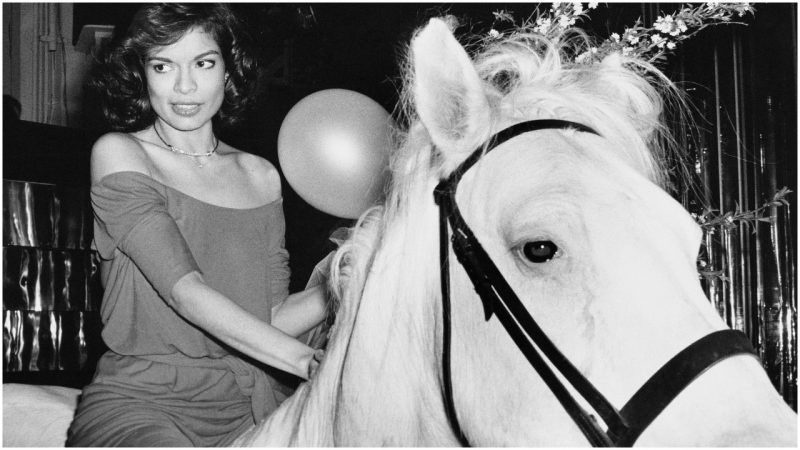

Regulars included Andy Warhol, Cher, Grace Jones, Truman Capote, and Liza Minnelli. Clever stunts generated massive publicity. For a birthday party held in her honor on May 2, 1977, Bianca Jagger rode a white horse across the dance floor, making for a sensational photo that splashed across newspapers around the world. It wasn’t the only time real animals were brought to the disco—to honor Dolly Parton, Rubell created a farm scene complete with chickens and donkeys. Reportedly unamused, Parton spent the party at a safe remove in the balcony.

Many were famously turned away. Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards of Chic wrote the song “Le Freak” after they were denied entrance past the velvet ropes one night. In an ironic twist, the song would become a disco hit that propelled dancers on the floor of Studio 54.

Widespread adulation must’ve made Rubell feel untouchable. In 1977, while the club made millions, it paid only a reported $8,000 in taxes. Cash was stuffed into garbage bags, hidden behind ceiling panels, smuggled out to Rubell’s home. He gave Andy Warhol a garbage can full of crisp dollar bills as a birthday present. In a fatal error, the disco king combined the sins of avarice, hubris, and pride by bragging about his ways. “What the IRS doesn’t know won’t hurt them,” he said on a local radio show. And to New York magazine: “Only the Mafia makes more money.” It was almost as if Rubell were taunting the government to come after him. It did. He lost.

IRS agents raided Studio 54 in December 1978, seizing cash, financial documents, and drugs, according to Rolling Stone. Accused of skimming $2.5 million off club earnings, Rubell and Schrager pleaded guilty to tax evasion and received the maximum sentence of three and a half years, a term that was longer even than they had operated Studio 54.

Studio 54 threw one last wild bash before the owners were locked behind bars. Such faithful revelers as Warhol, Jager, and Diana Ross showed up to bid the scene adieu. While Rubell was in prison, where he remained for just under one year, Studio 54 was sold for $4.75 million. The club continued to operate until 1986, though it became more a tourist attraction than an exclusive party. Today 254 West 54th street is the home of the Roundabout Theater. A restaurant Feinstein’s/54 Below operates in the basement.

Steve Rubell did return to the New York City scene as a hotelier and dance club owner, opening the Palladium on 14th Street in the 1980s, which hosted that era’s celebrated artists such as Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat. It was razed to make way for a New York University dorm. Rubell died of hepatitis and septic shock in 1989.