Why do objects fall toward the ground? The answer is, of course, gravity: the natural force that pulls objects to fall toward the earth. From Aristotle’s ideas about falling objects through the Newtonian equation and Einstein’s general relativity, all the way to the discovery of gravitational waves in 2016, the debate and our understandings of gravity have evolved throughout the centuries.

It seems that we have overcome gravity in some way with the invention of kites, hydrogen balloons, aviation, etc., but as it appears, we haven’t been able to overcome this natural force completely. But imagine what it would be like if we all obtained a shield from gravity that would protect us from accidents. Would it save millions and millions of lives? This is what a man named Roger Babson had in mind when he declared war on gravity back in the 1900s.

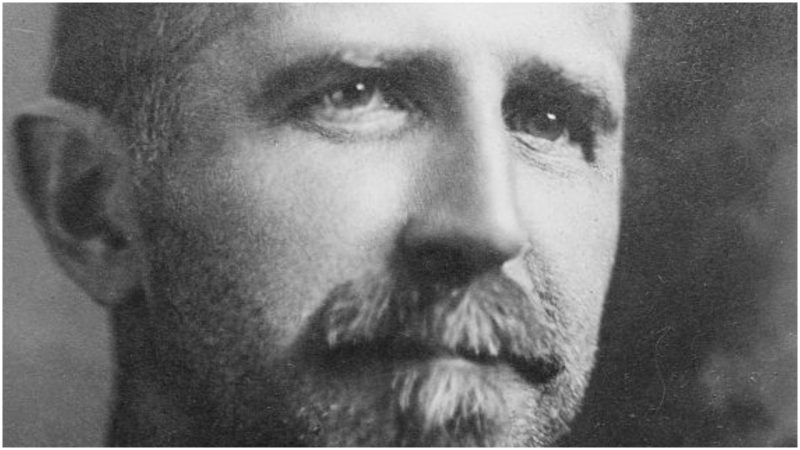

This MIT-educated genius was certainly not your average engineer. Instead of working as a railroad engineer, Babson chose to make a career in finance. He soon founded a statistical reports company and within a decade became a multimillionaire. He wasn’t your average multimillionaire, either. Namely, in 1919, he founded the Babson Institute that later became Babson College, wrote several books on investing, ran for president against Franklin Roosevelt, wrote columns about business matters for the Saturday Evening Post and the New York Times, and advised every president from Teddy Roosevelt to Franklin Roosevelt.

The eccentric businessman had a strange desire: to defeat gravity. He was obsessed with the idea that one day the force of gravity could be overcome. “It seems as if there must be discovered some partial insulator of gravity which could be used to save millions of lives and prevent accidents,” he wrote in the essay Gravity-Our Enemy Number One.

He noted that his interest in gravity started back in 1893 when his sister, Edith Babson, drowned in a river near Gloucester, Massachusetts. “When I was a boy, my oldest sister was drowned while bathing in Annisquam River, Gloucester. Mass. Yes, they say she was ‘drowned,’ but the fact is that, through temporary paralysis, or some other cause (she was a good swimmer), she was unable to fight Gravity, which came up and seized her like a dragon and brought her to the bottom. There she smothered and died from lack of oxygen,” he wrote in his essay.

In 1947, when Babson was 72 years old, his grandson, Michael, also died by drowning in Lake Winnipesaukee. It was after this incident that he became determined to do everything he could in order to get rid of gravity.

He wrote in Gravity-Our Enemy Number One: “There are thousands of such accidents every summer, notwithstanding the fact that most boats carry life preservers which are practical anti-gravity aids. If these would be more freely used, deaths from drowning would greatly be reduced, but most people–especially good swimmers think it is a sign of weakness or is sissified to use these aids for fighting Gravity. This is a great mistake and should be corrected by all swimming teachers”.

In 1949, he founded the Gravity Research Foundation, a research facility established in the town of New Boston, New Hampshifacility establishedoston to survive if the city was hit by a nuclear bomb. The research facility was supposed to develop a system that could shield people and objects from gravity. In order to encourage scientists to research the subject of gravity, Babson created a prestigious annual prize for the best scientific paper on the subject. Stephen Hawking, Freeman Dyson, Roger Penrose, and Martin Rees were among the winners throughout the years.

In nearly two decades of active existence of the Gravity Research Foundation, a number of conferences on the subject were organized. The foundation even began awarding “gravity grants” to schools that would allow them to erect a granite marker on each campus. One such example, from Tufts University, that you can see bellow states, “to remind students of the blessings forthcoming when a semi-insulator is discovered in order to harness gravity as a free power and reduce airplane accidents.”

The Gravity Research Foundation gave “gravity grants” and monoliths to 13 colleges and universities.

Roger Babson died in 1967, but the Gravity Research Foundation still exists today and the essay award lives on, offering prizes of up to $4,000.