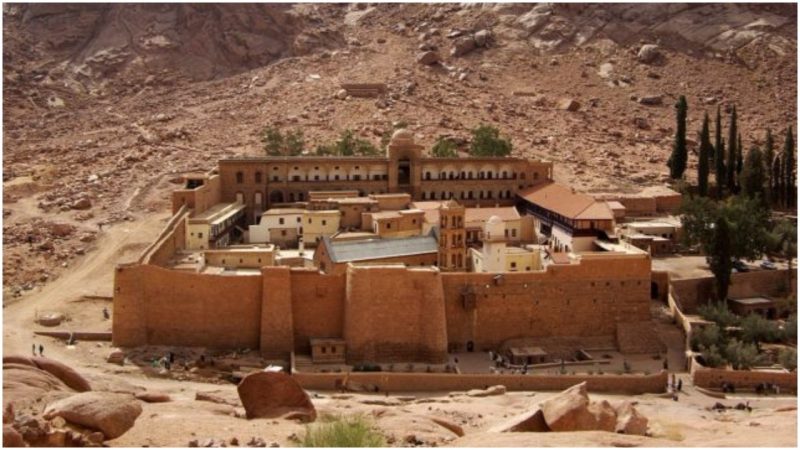

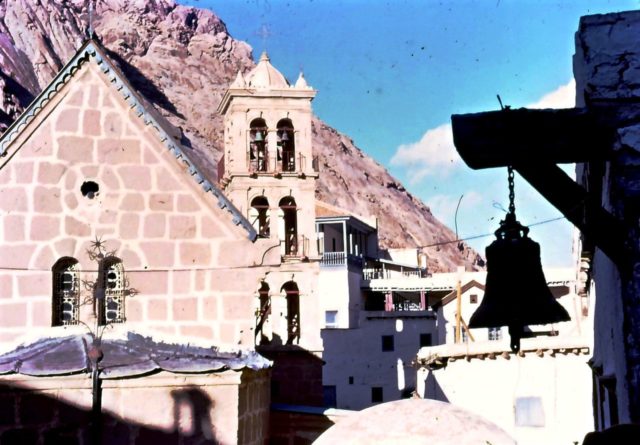

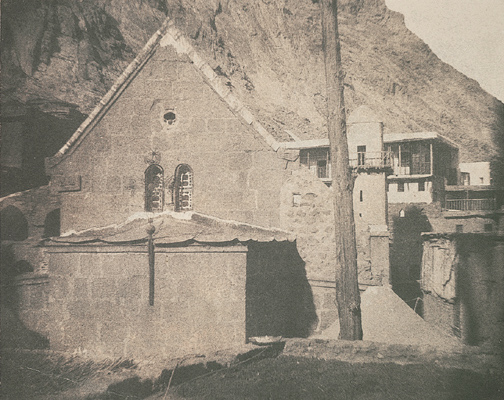

One of the word’s oldest preserved libraries, one which contains numerous ancient manuscripts, is to this day kept safe in a 1,500-year-old monastery on Mount Sinai in Egypt. The Saint Catherine Monastery, around which the small town of Saint Catherine grew, holds a heritage only fully known by the monks and hermits who’ve resided in it over hundreds of years.

For quite some time now, linguists, archaeologists, philologists, and other researchers had been drawn to the treasures that the monastery keeps. This is one of the last remaining Christian sites in these parts as turbulent historical events, such as the Crusades, wiped out most of the Christian medieval strongholds on Mount Sinai.

According to The Atlantic, this made the fortified monastery isolated, and even though it affected the lives of its residents, the isolation helped preserve these priceless documents of times long gone. In addition, the dry climate played a major role in their preservation.

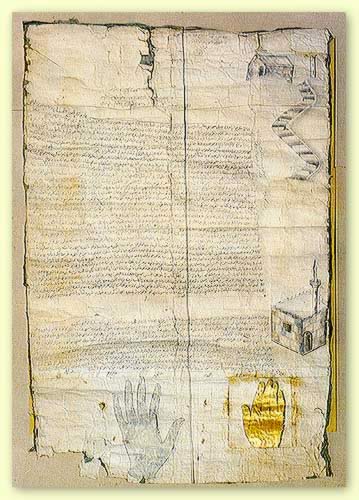

What it also did was force the scholars to constantly re-use their scrolls for writing as supplies of paper became more and more sporadic.

As The Atlantic explains, the monks would carefully wash the pages of the oldest manuscripts, because they considered them irrelevant, with lemon juice, and then scrape the writings off. The very core of these ancient manuscripts had been rewritten hundreds, perhaps even thousands of times.

So, the Saint Catherine Monastery holds secrets that can fundamentally change the way we perceive that period of early Christianity, and times long before that. But what exactly are the scientists looking for?

As the Independent informs, the latest research has focused on retrieving the texts that had been covered by layers of other texts in order to reuse the scrolls in times of need. These manuscripts are called palimpsests and the discoveries they hold within them had already shaken the scientific community.

In order to successfully decode the palimpsests, the scientists are using a combination of different lightings, including ultraviolet and infrared, as well as different angles of approach that enable the highly sensitive cameras to register all former inscriptions on these millenniums-old papers.

Richard Grey of The Atlantic explains how the researchers have photographed the palimpsests from each side, sometimes using unusual angles in order to “highlight tiny bumps and depressions in the surface.”

With the help of a computer algorithm, scientists are able to distinguish the older inscriptions from the ones that were rewritten over the course of time.

The results have been fascinating. The Early Manuscripts Electronic Library, an organization dedicated to the digitalization of ancient manuscripts, reported that there are at least 130 palimpsests among the 68,000 pages of manuscripts that are held inside the thick walls of the monastery.

The documentation and research of the Saint Catherine palimpsests started in 2011, and it has continued to unravel ever since.

What really makes these discoveries relevant is that, apart from the standard and well-studied languages of ancient Greek, Latin, and Arabic, several obscure and extinct languages are beginning to be revealed within the manuscripts. For example, a rare dialect of Christian Palestinian Aramaic had been discovered among the layers of texts―a discovery that can bring major breakthroughs in reconstructing such a defunct language.

This dialect is older than the Hebrew-influenced Jewish Palestinian Aramaic and Samaritan Aramaic and therefore sheds light on a culture far less known to historians, which would otherwise be discarded and most probably forgotten.

Michael Phelps, the director of the Early Manuscripts Electronic Library, illustrated the significance of such discoveries in his interview with The Atlantic, referring to the speakers of the forgotten dialect:

“This was an entire community of people who had a literature, art, and spirituality. Almost all of that has been lost, yet their cultural DNA exists in our culture today. These palimpsest texts are giving them a voice again and letting us learn about how they contributed to who we are today.”

Another great breakthrough involving a lost language is the finding of layers of text written on Caucasian Albanian. The language originally spoken in what is now known as Azerbaijan has only left several traces on stone inscriptions that miraculously survived to this day.

The words have already been added to a scarce vocabulary of a language that is yet to be reconstructed. In addition, scientists involved in this project have managed to decipher around 108 pages of never-before-seen poems by unknown authors, written in standard tongues such as Ancient Greek.These include a discovery of a medical script attributed to the father of ancient medicine, Hypocrites himself, and this could well be his oldest one found to this day. The analysis of these texts is yet to be fully conducted, after which, who knows what kind of magical discoveries will happen.