The majestic city of Persepolis, once the “wealthiest city under the sun,” as noted in the writings of Diodorus Siculus, was a grandiose showcase of the Achaemenid Empire. When it was built in the 5th century, the Persians ruled over an estimated 44 percent of the entire human population. And even though it was placed in the middle of nowhere, far from any political or strategic spot, Persepolis was truly made to impress and to underscore the immense power of the Persian kings.

Persepolis, which means the City of Persians, was called Parsa and was quite a curious complex. It was located in a mountainous region that wasn’t easily approached and was visited usually only in the spring and summer because roads during the rainy season turned into mud. Nevertheless, it was the seat of the government, designed for royal receptions and celebration festivals.

Darius I, who ruled from 522 to 486 BC, started the construction in 518 BC at the place chosen by Cyrus the Great, the founder of the Achaemenid Empire. Xerxes I finished the construction during his rule (486-465) and most of the palace is his work.

It was located 37 miles to the northeast of Shiraz on the east side of the Mount of Mercy (Rahmet Mountain), which was cut into in order to provide space for the platform of the 1,345 square foot terrace.

The royal complex that represented visual microcosms of the empire included the Apadana or Audience Hall, the Throne Hall, The palaces of Darius and Xerxes, the Gate of all Nations, the treasury, and the harem. According to the historian Diodorus, Persepolis was enclosed by three walls (first 7 feet high, the second about 14 feet and the last one 30 feet tall) and towers always heavily manned.

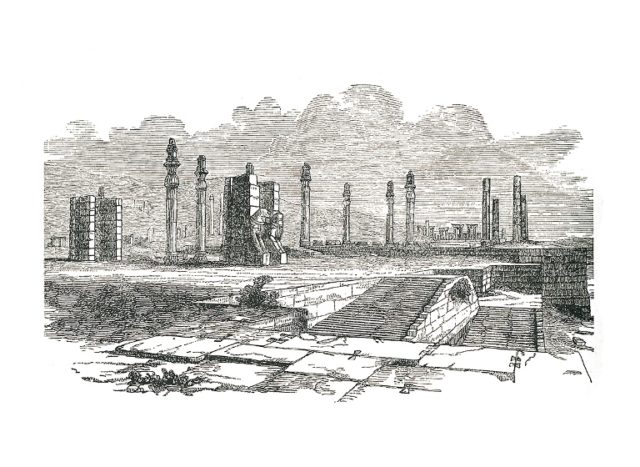

One of the most characteristic features of this architectural gem is the Persepolitan Stairway, which is built into the western wall and believed to have been originally intended as the main entrance to the terrace. The two symmetrical 23-f00t-wide staircases have 111 shallow steps.

They are full of processional reliefs of dark gray stone rendering the 23 nation representatives of the empire with their offerings to the king in repetitive scenes. Even today, one can identify the represented nations as Egyptians, Indians, Tajiks, Bactrians, Assyrians, and so on by their cultural accessories and physical appearance.

Both the eastern and western entrances to the grand hall of the Gate of All Nations, built by Xerxes, are guarded by two lamassu, protective deities with the body of a bull and a human head. There is also inscribed in three languages the name of Xerxes so it would be known that he ordered their construction.

The Throne Hall, or Hundred-Columns Palace, consisted of one large room made of limestone and decorated with reliefs depicting throne scenes and scenes of the king fighting monsters. Its construction was begun by Xerxes and completed by his son Artaxerxes. Initially an important reception room, it was later used as a storehouse for the treasury. The Apadana was even larger than the Throne Hall. Built first by Darius and finished by Xerxes, it was the main audience hall. Seventy-two impressive columns topped with carvings of animals supported the roof of the grand hall.

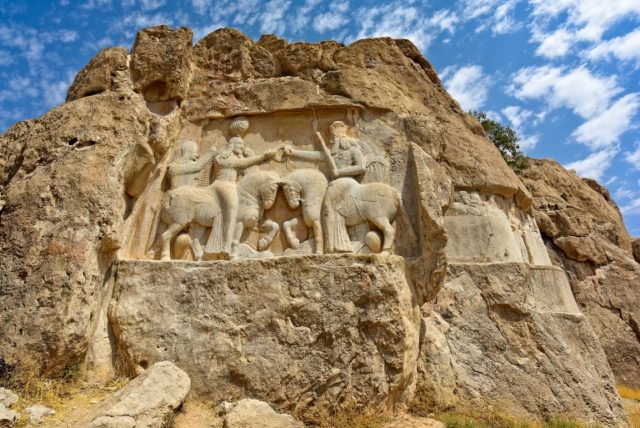

It was an edifice full of gold, silver, precious stones, and ivory, as were all other buildings. Near the site are found three tombs that are carved into the Husain Kuh Mountain. It is believed that Darius the Great, Xerxes I, Artaxerxes, and Darius II are buried there. The façade in the form of a cross has a relief of the king and the Ahuramazda’s winged disk, chief god of the Zoroastrian religion worshiped by Persians. The entrance to the tomb is high from the ground and leads deep into the mountain.

Today, only 13 of the 37 columns are still standing, since the city went through a devastating history of destruction. Nevertheless, it continues to be the symbol of the strength and glory of the Achaemenid monarchy. Alexander the Great, known for his daring and sometimes cruel temper, gave the order for the city to be burned to ashes in 330 BC. There is speculation he did it to revenge Athens, which was burned by Xerxes in 480 BC. But there are also theories he did it to highlight his complete victory over the Persian kingdom. It is not confirmed what was his real reason, and there are many different accounts of it, one of them provided by Diodorus Siculus:

“When the king had caught fire at their words, all leaped up from their couches and passed the word along to form a victory procession in honor of the god Dionysus. Promptly many torches were gathered. Female musicians were present at the banquet, so the king led them all out to the sound of voices and flutes and pipes, Thais the courtesan leading the whole performance. She was the first, after the king, to hurl her blazing torch into the palace. As the others all did the same, immediately the entire palace area was consumed, so great was the conflagration.”

After that, Alexander took all the treasure on 20,000 mules and 5,000 camels, according to Plutarch. In 1602 Antione de Gouvea was the first European to visit it, and in 1618 it was identified as Persepolis.

But it wasn’t until 1931 the archaeological excavations began under the supervision and sponsorship of the Oriental Institute of Chicago. In 1979 UNESCO listed it on its World Heritage list. It is a site of previous glory that still provokes amazement and admiration.