“Honored guests, I am proud to welcome you to this gala, celebrating the life and work of Georges Méliès. For years most of his films were thought to be lost. Indeed, Monsieur Méliès believed so himself. But we began a search, we looked through vaults, through private collections, barns, and catacombs. Our work was rewarded with old negatives, boxes of prints, and trunks full of decaying films that we were able to save. We now have 80 films of Georges Méliès. And tonight, their creator and the newest member of the Film Academy Faculty is here to share them with you.”

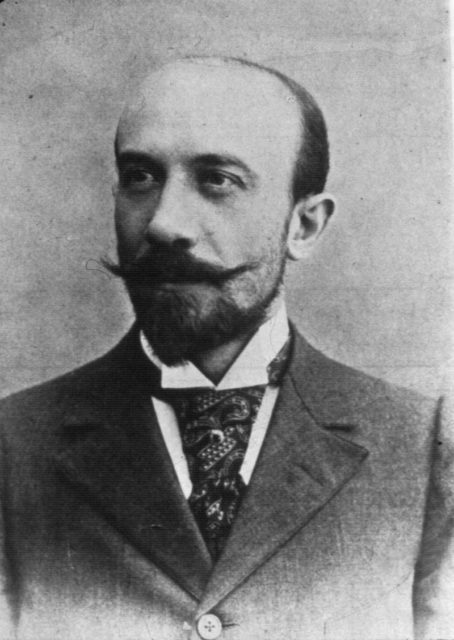

Méliès was one of those people whose world seemed more like magic than reality, and it’s a bit tricky to pick between illusionist and film director when one classifies him. Maybe because he was both: a dreamer and a cinemagician who had a machine in his mind that yielded a magic that would last forever. His immense contribution to the world of art is of such magnitude that his magical life story is hard to be packed into one single article.

So this one, for instance, starts off with the ending scene of a movie, and thank to none other than Martin Scorsese, who in 2011 unexpectedly paid a majestic, passionate tribute to the French pioneering filmmaker and master magician, a century after this man discovered film trickery and ignited the cinemas with that dreamlike magic that only movies can offer.

In 1895, the Lumière brothers screened their Sortie de l’usine Lumière de Lyon, or Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory, a 46-second sequence of moving pictures. It was followed by nine films of similar length in one of the first public screenings of the fledgling filmmaking business. Georges Méliès was among the audience to witness the Lumière’s cinématographe debut.

The screening was held in the basement at the prestigious Le Salon Indien du Grand Café in Paris and to Méliès’ great surprise, he came to be spellbound by it. But not by what he saw on the screen, albeit what he saw was pretty impressive, he was more fascinated by the limitless potential of their machine and what the cinématographe could do in the right hands. This was the moment when he first fell under the spell of the “camera” and came to be captivated by cinematography. It was the culmination of his longtime obsession with visual art and trickery.

The movies of the brothers were nicely framed, well shot, and impressive for the time. However, Méliès had the genius to envision a more creative application for this new medium. While the brothers believed that “the cinema is an invention without any future,” Méliès saw it in a way that probably could be best described with the words of David Lynch: “Cinema is like opening a door and go into a new world,” and in a blink of an eye made it possible for such a line to even exist.

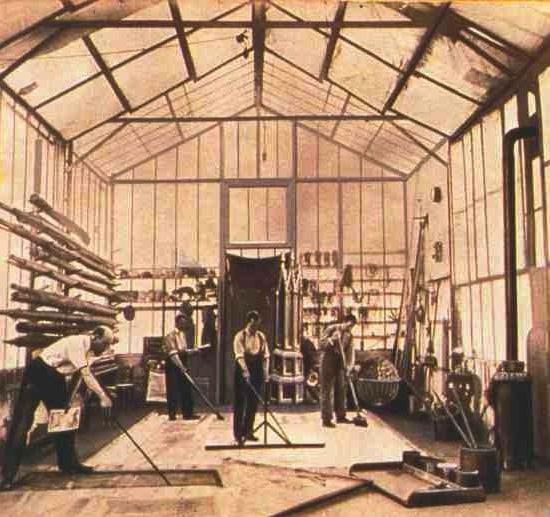

A year after the Lumière’s screening, Méliès found a film projector. It was his new toy, and he wasn’t going to calm down until he learned every piece of it. In the end, he figured out how he could modify it to the extent that he turned the projector into a film camera. In the following years, up until 1913, he wrote, produced, directed, edited, and acted in no less than 500 shorts. All in all, Méliès created a one-man show where, by hand painting every single frame on the film reel or gluing one over the other, he invented animation, editing, and multiple exposures. He made singing heads float into the air, performers act opposite themselves, and even people disappear in an instant. Just as almost all of his movies disappeared after his film studio, the first ever was taken from him and used as a hospital at the start of World War I. Méliès was left in poverty, stripped away from everything he had achieved. It is even said that the reels were used for heating, for they were good for starting a fire, and nothing else was to be found.

Fortunately enough, some were not set ablaze and now serve to prove exactly what Georges Méliès did for cinema. Because, while Auguste and Louis Lumière invented the process of filming, this man invented filmmaking, back when it was considered magic, and as it remained to be for many years.

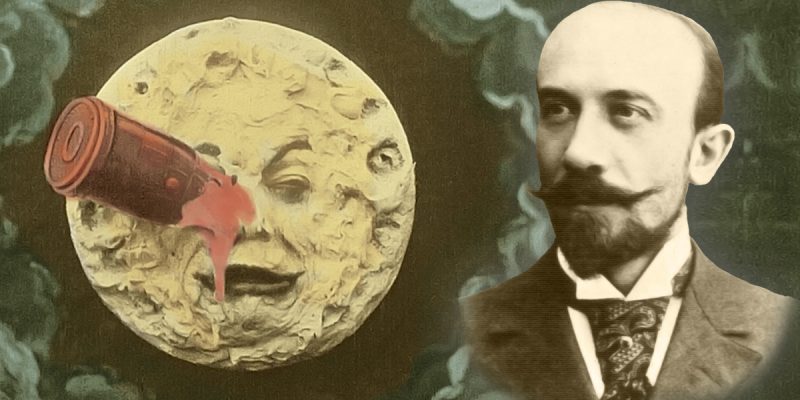

Among the few film reels that were rediscovered many years later is his best and most celebrated work, in which he wonderfully visualized a satirical representation of Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon and H. G. Wells’ First Men in the Moon. His marvelous Le Voyage Dans la Lune.

One can only wonder how thrilled its first viewers must have been back then, as this movie of his delivers some inexplicable freshness even today, although it is more than 100 years old. A few years back it was relayered in color, frame by frame, and the French pop duo Air provided one highly original score to supplement it, as a pure and delightful treat for all the senses.

Artists have the ability to create something out of nothing and give life where previously there was none. As for filmmakers, well: “I love it when you go to see something, and you enter as an individual, and you leave as a group. Because you’ve all been bound together by the same experience,” – Tom Hiddleston. And Monsieur Méliès made it possible for us to have the pleasure and experience this.

Ladies and gentlemen, I… I am standing before you tonight because of one very brave young man who saw a broken machine, and against all odds, he fixed it. It was the kindest Magic trick that ever I’ve seen. And now, my friends, I address you all tonight, as you truly are. Wizards, mermaids, travelers, adventurers, magicians…Come, and dream, with me…

This is how Ben Kingsley in Scorsese’s Hugo welcomes his audience, right before he pulls the curtain and takes them on a surreal trip to the Moon, just as Monsieur Méliès did back in 1902 when his 14-minute masterpiece, A Trip to the Moon (Le Voyage Dans la Lune) first came out. Long before rocketry was even a thing and moving pictures were precisely what the name states, pictures that moved and nothing more.