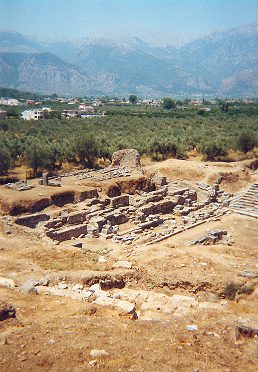

“These Are Sparta’s Walls”

According to one of the greatest Greek historians, Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus, more commonly referred to as Plutarch, when anyone would question the city’s lack of fortification and dared to ask the king “where is your wall,” he would simply point in silence towards his Spartans as an answer.

They held a not so humble belief that “a city is well-fortified when it has a wall of men instead of brick,” (Lycurgus) for bricks can fall and be conquered, but a Spartan never will. And rightfully so.

The army of Sparta is recognized as the most formidable in the history of man, and according to Plutarch’s book On Sparta, their men were trained to be tougher than a brick indeed. Every male child belonged to and was raised by the state. He was put through a vigorous training unlike any other child in history and endured such harsh education that the word “spartan” literally became an adjective for “showing, or characterized by, austerity or a lack of comfort or luxury,” a synonym for an austere way of living.

If you were born a Spartan, you were born a soldier, and there was no way around it. Men were not merchants, nor writers or poets, nor farmers. They were soldiers first and foremost and everything else was just a side job, and all those other things a man could do were only trivial things he could do in his free time, which was almost nonexistent. Every healthy baby was enlisted as a soldier from birth and his education made sure he stayed as such for life.

Let us assume that it is the year 398 B.C., the Peloponnesian War (431–404) has just ended and Sparta, exiting as the victor against their enemies, is probably at its strongest point under the rule of King Agesilaus II. It’s been almost 500 years since Lycurgus, the legendary law-giver, reformed the state with his military laws and made Sparta, Spartan.

Now let’s say a baby is born, a good and healthy baby boy. He’s been checked by the state doctors. His fate will be nothing alike the infant next door, who unfortunately was born with a sign of birth defect so his father had to take him to the Apothetae, a pit down the hillside, where, defenseless, the baby was left to starve to death under the scorching sun. According to Plutarch, the practice was to toss every ill-born spartan baby boy from Mount Taygetus into the abyss. However, judged from a practical point of view, this is probably a myth developed over the years and it was the pit nearby for these poor babies rather than far up to the mountain.

So our baby, named Demetrius by his parents, meaning Lover of Earth in Latin, has passed his first test. He is now put into a bucket full of wine and washed with it instead of water so he can be tested again to see if he is worthy enough to be raised. If he breaks into a crying tantrum or exhibits signs of any kind that he rejects this experience, he is regarded as ill with some hidden, incurable disease such as epilepsy, or at the very least deemed unfit and unworthy to be raised and sent off to slavery and a life as a helot (slave).

Luckily, our Demetrius seems to enjoy the wine-bathing, and now will continue to be raised by his mother until the age of seven, but never cuddled. He will be left alone in darkness on purpose so he would never fear darkness nor solitude. But he is lucky, for more than a half of the babies never even make it this far.

Everything goes as it should and Demetrius, alive and healthy, is about to celebrate his seventh birthday. And as a present, just as any other seven-year-old in Sparta, he is removed from his parents’ home and sent to the military barracks so he can start his education, the Agoge, which meant to mold him and all other young boys into skilled warriors, and the best possible versions of themselves. Here, under a strict regime and tutored by his “Warden,” our boy begins to learn the rules of combat. By engaging in stealth practices, athletic exercises and hunting in the nearby woods, he is preparing his body for warfare, whilst all the time not neglecting his scholastic education and learning everything about music, math, and philosophy. While these were the things he could never become to do full time, the knowledge of them is meant to give him an advantage in combat and determent the outcome of any battle.

And it isn’t easy, not for him nor any other kid for that matter. By the age of 12, every participant in the agoge is stripped of all his clothes and common luxuries. Barefoot and almost naked he was left to sleep out in the open, and fed so little so he can only survive the day, but enough to know what is good and feel the need to hunt for himself in the evening, steal it, or fight for it with the other boys and survive. However, while they were left and encouraged to scrounge for food in any way, they were severely punished, whipped and beaten almost to death if they were caught for stealing or left to their own demise and the mercy of the boy whose food was stolen. On special occasions, they were even dragged to a pit and with cheese placed in the middle, and ordered to fight for it.

Agility, strength, and perseverance aside, to test their academic advancement and ability to make quick but well thought out decisions, every night when the supper was over, a warden (their teacher) will sit among his students and ask a tricky question. Kind of like today’s quiz shows, when contestants are called to buzz first and give an answer. The questions ranged from “Who is the strongest boy in this group” to “Why are you left out in the open without clothes and hungry” or even, “Why is knowing math important to us?” Their answer had to be reasoned, swift, sharp and well thought-out, even witty at times, or, as stated by Plutarch, a boy was to be bit on the thumb by another boy of his choosing. And for those who failed to answer whatsoever, a whip to the legs, so he can not hunt or steal for days. Our beloved Demetrius learns this the hard way.

If this was not enough, for them to be shaped as true “Spartans,” at the age of 20 the boys had to pass a rigorous test, and graduate as full citizens and real soldiers. Every year in Sparta a special festival called Diamastigosis was held. Among the many things, the most anticipated event of the festival was also the most brutal one, and this activity was the boys’ test of manhood. In a public manner, in front of every single Spartan and guests from abroad, all who made it this far were taken out and whipped until their conscience serves them. It seems like torture, but for Spartans it was the greatest honor of all, and all boys were eager to volunteer and withstand the pain and abuse longer than everyone else. These boys were trained to face abuse and never surrender under any circumstances. They weren’t just trained to be an unmovable brick in the Spartan wall, they were trained to be the unconquerable wall itself. They were trained to be Sparta!

All who cried for mercy under the whip for were labeled as perioeci, a middle class. They were still soldiers of Sparta, but a low life who later struggled to find a mate and form a family of their own. As for all the others, they were awarded aristocratic citizenship and continued to live their lives as soldiers within the barracks until their 30s, when they were deemed ready form a family and produce Spartans of their own.

As for Demetrius, well he learns to endure the pain, never shed a single tear or a cry for help. He lives on to fight the Battle of Leuctra against Thebes in 371 B.C. under King Agesilaus II. He lives to have the honor to be pointed at by his king as the wall of Sparta. He survives the battle and outlives his king as well, and lives to reach the age of 60 when he retires from any military activity, as Spartan Laws clearly stated.

He has a wife and family of his own, but never a Spartan boy. He has two little daughters, who in the same manner as the boys when they’ve reached the age of seven are taken from his home and sent to school to learn a few things. To fight, wrestle, and be proficient gymnasts, javelin throwers, and endure physical pain. For only a Spartan mother could bear a strong Spartan child later on.

Our Demetrius, who we only imagined so we can tell a tale of Sparta and how it came to be feared for centuries, dies right after his daughters are taken away from him, but never buried under a tombstone. For that was an honor reserved only for those who died in combat.