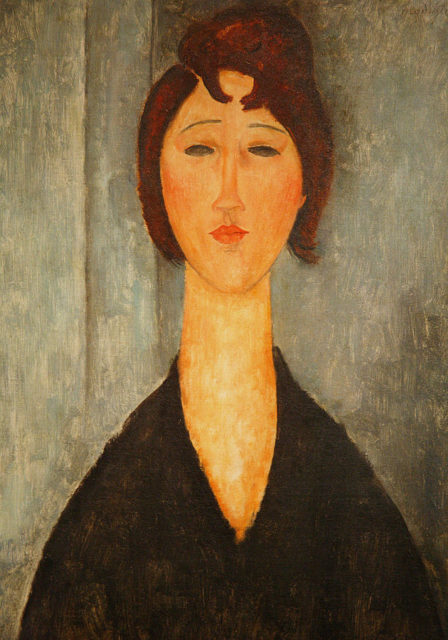

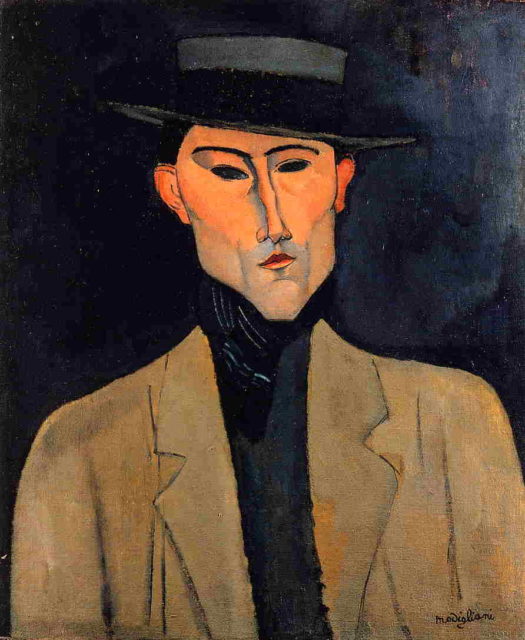

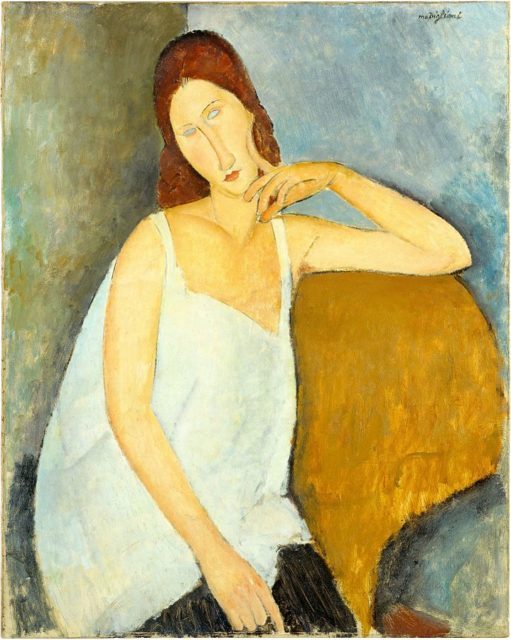

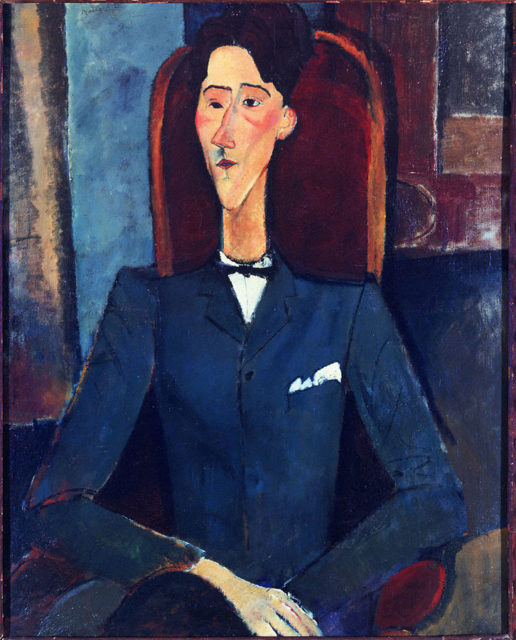

Of all the striking characteristics seen in Modigliani’s portraits are the elongated visages or the disfigured features, the mysterious, hazy eyes of the sitters capture the true essence of the painter’s style. Known for his many portraits of young women and reclining nudes, the eccentric Modigliani is now ranked among the modernist, expressionist giants Pablo Picasso and Edvard Munch.

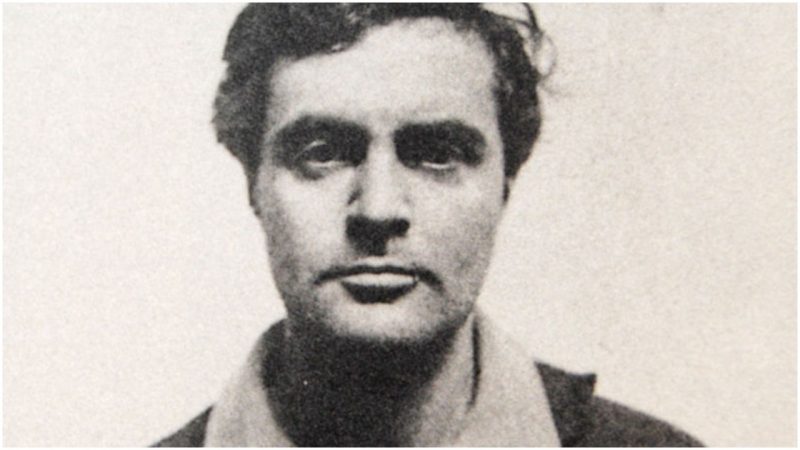

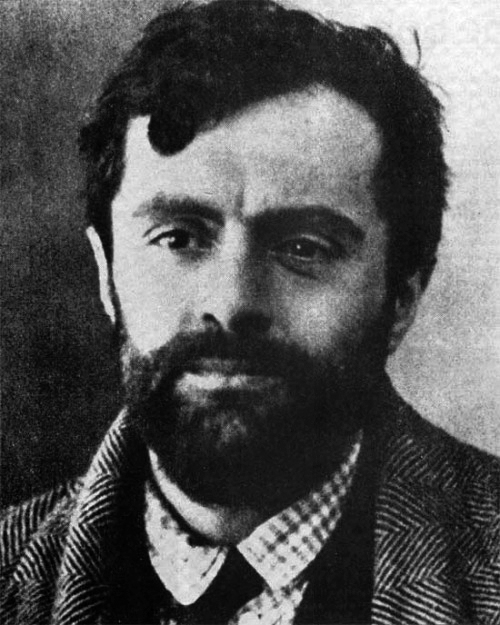

The fourth child of Flaminio and Eugénie, he came from a Sephardic Jewish family that lived in Livorno, Italy. The family was known for its scholarly, wealthy status but collapsed financially, only to be saved by the birth of Amedeo himself. According to the law, creditors were not allowed to confiscate property while a mother is pregnant or with a newborn baby, so Modigliani’s father was able to save just enough of the family assets to make a living by piling them up on top of the mother’s bed.

He had a close relationship with his mother, who was also fond of art and taught the sickly and frail Modigliani at home until he was 10. The health problems caused by tuberculosis, which would later take his life, prevented the young man from having a formal education.

The artist tried to mask the “embarrassing” disease with heavy drinking. Modigliani was happy to let people consider him an alcoholic and drug addict, rather than face accusations of being a man suffering from tuberculosis, a highly infectious disease that was then regarded as scandalous.

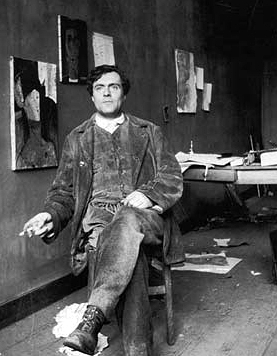

Even though he came from a bourgeoise family, he believed that the most honest artistic drive came from suffering. Following the example of Vincent van Gogh, Modigliani embraced the notion of the archetypal starving artist.

Regarded as the “prince of vagabonds” in the art world, Modigliani’s womanizing and alcoholic lifestyle meant poverty for him. He was even known to exchange his paintings for meals at restaurants. Ironically, his work became highly valuable after his death at the age of 35. Reclining Nude with Blue Cushion would became one of the most expensive paintings ever sold, bought by collector Steven Cohen in 2012.

Amedeo Clemente Modigliani worked mainly in France, and he is well known for his oval portraits and nudes, characterized by his style of elongated faces and doll-like figures. Although his paintings were dismissed during his lifetime, they would go on to become a classic staple of modernist portraits.

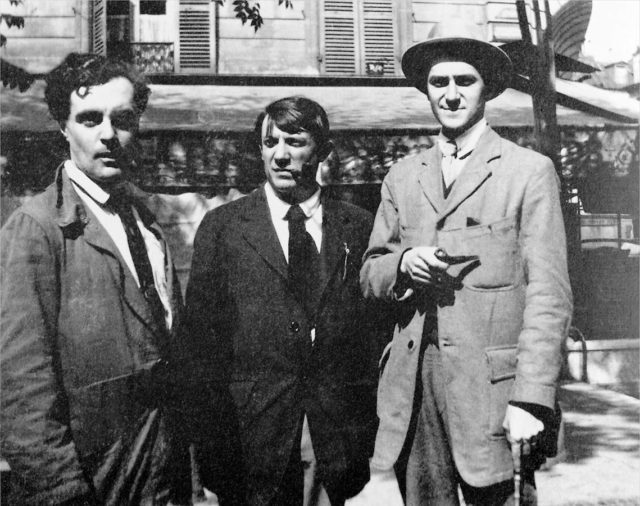

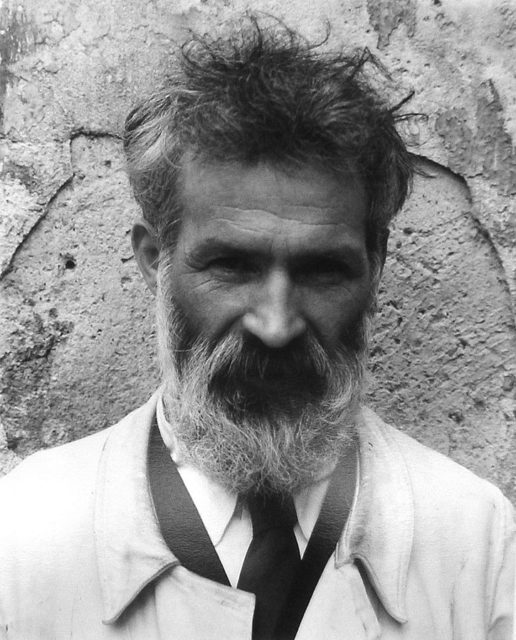

After his Renaissance studies in Italy, he moved to Paris in 1906. There he met many key figures like Pablo Picasso and Constantin Brâncuși in 1909, whose modernist style of sculpting was admired by Modigliani and would later serve as his main influence, along with the long, curved lines of distinctive African art.

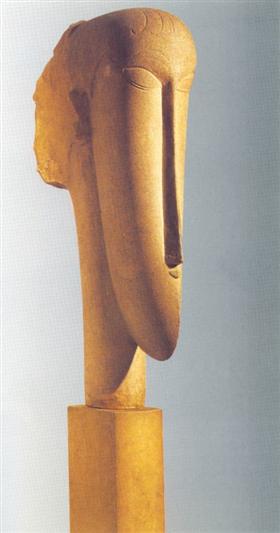

Brâncuși gave Modigliani a lot of insight and advised him to take up sculpture. He had the honor of exhibiting eight sculpted stone heads at the Salon d’Automne, the elongated and minimalistic forms directly reflecting his inspiration from African sculpture. Modigliani was sadly forced to abandon his sculpting endeavors because the dust strained his health even further.

Only Modigliani’s “Tête,” a series of modernist limestone masterpieces, remain as an untarnished example of what sculpting sorcery Modigliani was capable of. He produced about 25 known sculptures and they had a significant impact on Modigliani’s style of figure and portrait painting.

Modigliani’s “blank-eyed” portraits began much later in his lifetime. It should be noted that even if there is an absence of the “windows to the soul,” the subject’s character is reflected through their elongated gesture. A simple head tilt could say a lot about the woman or man on the canvas.

The hazy bedroom eyes, which further emphasize the person’s obscure nature, weren’t well-received at the time. Modigliani’s aim was to simplify the fundamental essence of a person’s character, directly stating their temper or intention without risking losing it among the gestures of cliche artistic poses.

As for his nudes, Modigliani successfully scandalized every audience in Paris with raw depictions of the female body. In his paintings, he didn’t fear to limit the volumes of the subject’s contours and curves. Thus, features like the pubic hair in Modigliani’s nudes pushed the Paris police so far as to shut down his only solo exhibition in Paris on December 3, 1917, just hours after its opening. The exhibition continued on the following day, but with the nudes removed from view.

Modigliani stepped up the game in the conventional tradition of nude painting. The reason why they weren’t hailed as revolutionary was likely due to their candid sensuality. In his drawings, Modigliani tried to give the function of limiting or enclosing volumes to his contours. They were noticeably devoid of all modesty and the classical notions that had always been depicted in a mythological context, be it Roman gods or Ancient Greece heroes.

Modigliani’s portraiture manages to grasp the unique marriage between a specific theme and absolute generalization. But the attempt to convey the personalities of the dead-eyed subjects sadly fall into uniformity, while his trademark style and recurring long-neck motifs may well be regarded as a pattern of artistic concept.

Modigliani viewed caricature as a medium for portraying human archetypes, much to the dismay of the harsh, conservative art critics, who believed this style took away the seemingly uncontrived magic behind the sitter’s eyes.

But if Modigliani’s portraits are to be viewed as bland masks, along with the emptiness of their unnerving, squinted eyes, they are masks that still fulfill their prophetic message, showing the viewer a lot more to the portrait’s sameness–their innermost nature. A true conceptual paradox.

Although Modigliani was crippled with disease and tragedy, he gleefully painted portraits of friends, acquaintances, professional models (when he had money to spend), lovers, and even people he met on the street, inviting them to sit for him, as opposed to painting on commission. He only painted the eyes of those who were close to him, above all respecting the fragile integrity of the person’s soul.

One might say that he ended up becoming a painter of characteristic archetypes. Be it nudes, collectors, drinking buddies, seated women, they all fell into Modigliani’s hazy-eyed chasm.

Simple at first glance, his portraits reveal an enticing, appealing depth. As an honest artist, he did not attempt to shock or expect any reaction from the public with his unconventional style, but simply to say “This is what I see.”