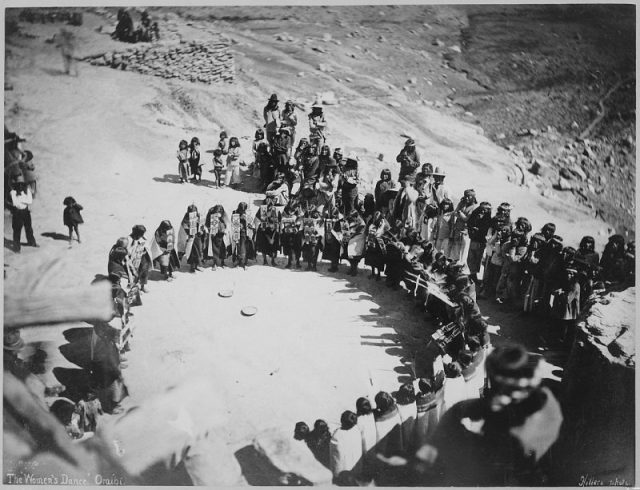

For millennia, the ancient Hopi people, recognized for their profoundly traditional way of life and deep spiritual beliefs, have inhabited the same realms. They are noted for being the perfect guardians of their rites, which often take place in underground chambers called kivas. Emily Benedek, an author who has penned two highly praised books on the Native Americans of the Southwest, notes in The Wind Won’t Know Me that “in spirit and in ceremony, the Hopis maintain a connection with the center of the earth, for they believe that they are the earth’s caretakers, and with the successful performance of their ceremonial cycle, the world will remain in balance, the gods will be appeased, and rain will come.”

In this context, kivas carry symbolical meaning and can be regarded as one of the central aspects of the culture of the Hopi. A tiny hole in the floor of these chambers is supposedly the entrance to the underworld, whereas a ladder moving up above an opening on the roof is believed to be the pathway to this world. Such rooms have found their place in traditional Hopi villages–which today count 12 and are situated on three mesas–and they still take the spot of just below the central square of the village.

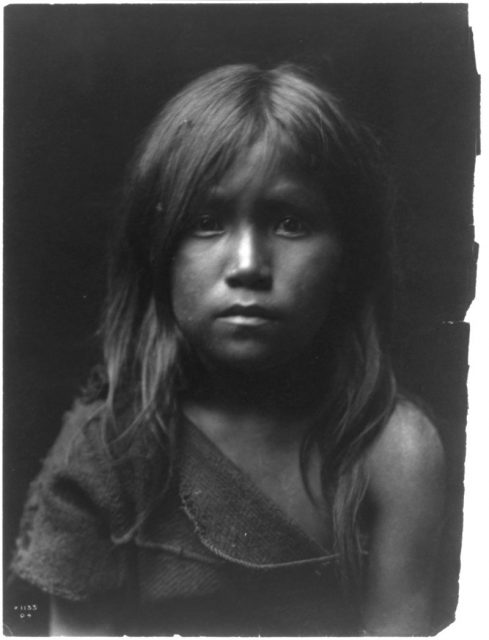

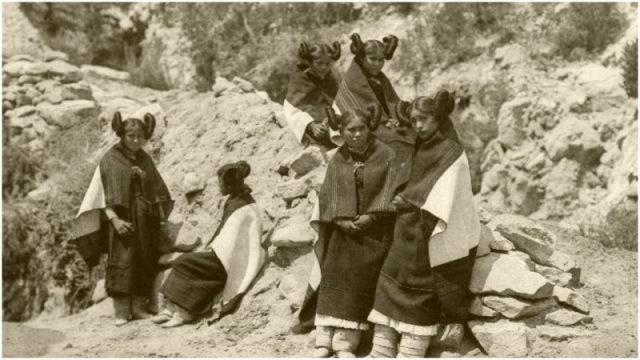

Hopi mother, 1922

Because many of the Hopi rituals are carried out in great secrecy, the details of the ancestors of the Hopi are uncertain. It is believed that they descended from the Ancestral Pueblo, just like other Native Americans inhabiting the Southwest (not counting the Navajo, with different ancestry and with whom the Hopi have had a history of disputes).

If Hopi traditional stories are to be believed, they came to this so-called Fourth World after an arduous journey in which they changed places for living before finally settling where they are today.

American writer Frank Waters, famed for his novels as well as historical works offering insights on the American Southwest, notes in one of his books that the Hopis “regard themselves as the first inhabitants of America,” and “their village of Oraibi is indisputably the oldest continuously occupied settlement in the United States.” For many other Native Americans too, the Hopis are perceived as worthy of such a description. A book entitled Hopi, and penned by Suzanne and Jake Page, says that other Native Americans regarded them as “the oldest of the people.”

Science and archaeology have affirmed that the Hopi tribe has been present in the Southwest for the last thousand years, possibly even longer than that. It was around the 14th and 15th centuries when the Hopi introduced chieftains to their villages as a means of better coordinating daily activities. This need arose as the villages grew in size. Farming is an essential part of Hopi everyday life, but there were other mounting tasks that demanded serious management. For instance, as one source notes: “coal was mined from mesa outcroppings, requiring unprecedented coordination.” And coal indeed found several uses, included firing up pottery, distinguishing the Hopi among the first peoples around the planet to start doing so.

It was around the same period when the Hopi started using the kivas as sanctuaries for their rites, as well as when Oraibi gained prominence as sort of a center of the Hopi culture. This happened following the demise of a couple of other villages, but regardless of the changes, the traditional way of life never ceased.

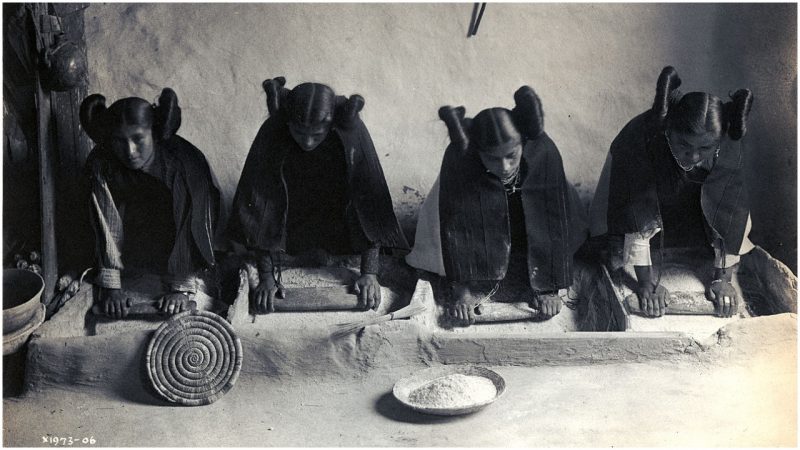

In the fields, the Hopi would take care of dozens of varieties of corn. Squash is also important, as much as a food as for producing tools, instruments, or kitchen appliances. Other favorites: pumpkins, beans, cotton, and sunflower.

The Hopis “first contact” with Europeans affected the community. It happened in 1540 when explorer Francisco Vásquez de Coronado brought with him a troop of Spanish soldiers. The Spaniards had reached the lands of the Hopis in a quest to find gold. It was a short first stay, in which the visitors were disappointed in finding no gold, so they decided to destroy a part of one village on their way back.

This violent first contact was perhaps an omen for the Hopi tribe in the future. They had to wait until the end of the 1620s for the Spanish missionaries to begin arriving. They came, of course, to preach Christianity, which the Hopi people pretended to accept, and meanwhile, continued their own rituals clandestinely. They did not tolerate the foreign preachers endlessly, however. Perhaps several decades passed, but the Hopis made sure to eradicate all missionaries.

But more Europeans started arriving, colonizing the continent in a quest to find a better future in the New World. Added to that were the ongoing disputes with the neighboring Navajo. Today, the Hopi count themselves as sovereign and live across a space of over 1.5 million acres located in the northeastern parts of Arizona, and east of the Grand Canyon.

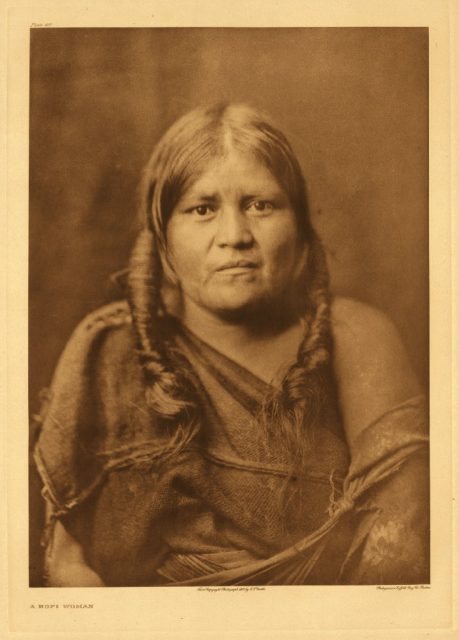

No matter what happened in history, the Hopis have managed to retain numerous aspects of their traditional way of life, and the past seems to be omnipresent regardless of which Hopi village visited. The emblematic terraced structures made of stone and brick keep the centuries-old architecture alive, and people still carry water to their homes perched atop the steep mesas. Families take care of the same fields their ancestors did centuries ago, and local craftsmen continue to produce the same jewelry and items they did in the past.