For many centuries, humans have put effort into representing the world as they knew it. The ancient Greeks created the first mathematically satisfactory maps of the world. A name to remember is Anaximander, believed to have drawn the first map of the world in the 6th century B.C., presuming that our planet was not spherical but cylindrical.

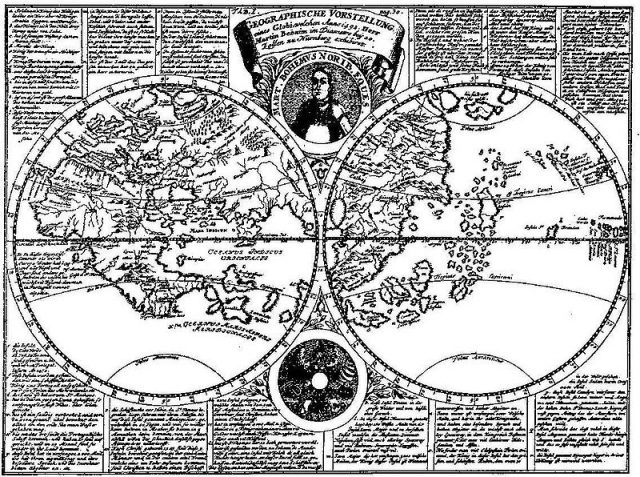

Then, two more names: Eratosthenes, who assumed that the Earth was spherical, hence he produced a map of the world; and Ptolemy, who made the first world maps employing latitudes and longitudes. His map also had a conical projection. Ptolemy is cited with producing the Geographia, around the mid-2nd century, in Alexandria, a work that was both an atlas and a treatise on cartography, and it displayed a couple of maps of the then-known world.

When it came to globe-making, this was a pursuit of the European Renaissance, and it flourished after technologies such as printing were introduced. Also important were translations of works such as Ptolemy’s Geographia, and this happened in the first decades of the 15th century.

Before the time that globe-making established itself across European territories, it should be noted that production of globes was well underway elsewhere, especially across the Islamic world. There, production of spherical maps of the world thrived. Celestial globes were principally used as instruments in resolving complex matters of celestial astronomy.

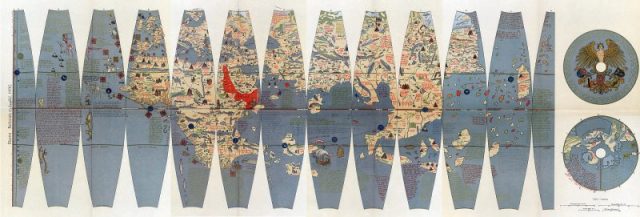

After more European voyagers started sailing the Seven Seas, globe-making became a more established craft in Europe. One globe that intrigues many because of its age and uniqueness of construction is the Erdapfel, German for “earth apple.” This is the world’s oldest surviving terrestrial globe. Credit for its creation goes to Martin Behaim, a polymath of his day who knew a lot about geography and philosophy–and was also skilled as a salesperson. His globe shows the world as people of the late 15th century understood it.

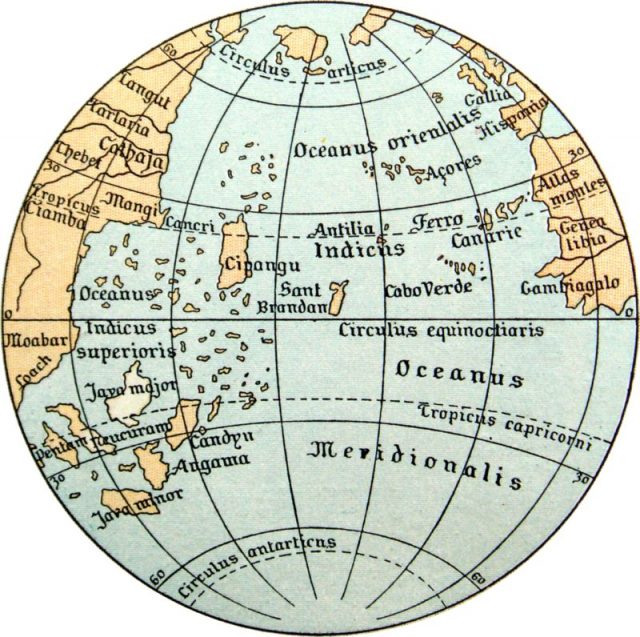

On the Erdapfel globe, the European continent, attached to Asia, appears to rule a good portion, with a large body of water that separates what would be the western-most part of Europe and the Far East of Asia. In the year it was finished, 1492, Columbus was still undergoing his arduous journey, therefore the Americas were not represented on the globe.

Another interesting observation is the representation of Japan, in those days better-known as Cipangu, thanks to accounts ascribed to Marco Polo. Here, Japan is positioned more to the south of where it actually is. There is also Malaysia, depicted wrongly as a vast peninsula, as well as some notable phantom places such as Saint Brendan’s Island, which people believed existed at some point in the North Atlantic, west of Northern Africa.

Before Behaim created this globe, he carried out many voyages abroad, included a visit to the coast of West Africa. He was the leader of the project and supplied all information needed for projecting Earth and for inserting the numerous illustrations onto the globe’s surface. He used various sources to fuel his vision of the world, included Ptolemy’s work, but still, even for his day, the globe had a significant number of inaccuracies and errors.

During the two years in which he worked on the project, several other people helped, such as Georg Glockenon, who painted the Erdapfel. Glockenon was a respected woodblock cutter and also did painting and printing. Once completed, the Erdapfel was exhibited in Nuremberg’s town hall. It is known that the globe stood there at least until the late 1500s, and after that, it passed into the hands of the Behaim family.

As intricate and lovely as it was, with hundreds of painted tiny figurines and objects depicting great kings and rulers, saints and mythical creatures, flags, and animals, the Erdapfel was forgotten by the Behaim family. It was in the 19th century that later Behaim generations rediscovered it and understood what a wondrous artifact of the past the Erdapfel was.

The family lent the artifact to the German National Museum in Nuremberg during the early 20th century. But just two years before the start of World War II, it was bought by museum officials following the wishes of none other than Adolf Hitler.

The Führer believed that the Erdapfel was an important artifact, and it should not be lost outside the borders of Germany. Ever since then, the Erdapfel has maintained its place among the valuables of the German National Museum. Though not the most accurate globe of all time, it is a reminder of the perspective of centuries past, a portrayal of our planet that is now long lost in the maze of history.