Achieving immortality is a topic ever recurring in human history, across various cultures. It appears even in the earliest important works of literature, such as the epic poem of Gilgamesh, in which the heroic King of Uruk, who is two-thirds god and one-third a man, sets out on an arduous journey–a quest to find the secrets of eternal life.

Gilgamesh begins his quest following the death of his almost equal and beloved friend, Enkidu, a death that horrifies the hero, making him abandon all the greatest joys of being a king such as wealth, power, and glory. As the story reveals, as soon as he finds a herb said to grant him eternity, or at least capable of reviving his youth, a serpent appears and steals it from him, concluding a lesson that immortality is perhaps something “reserved” only for the real gods.

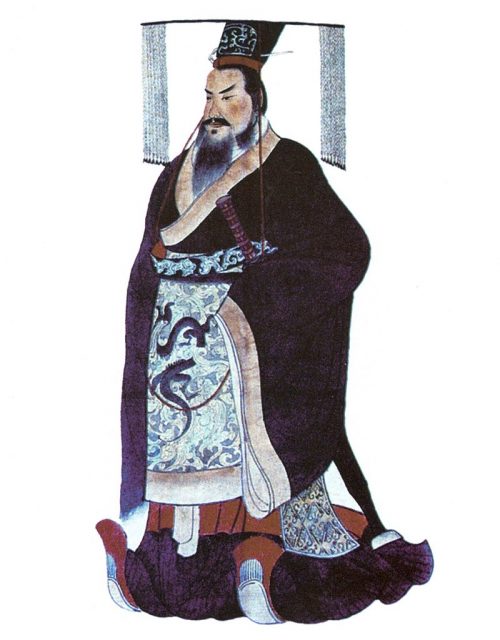

The first Chinese emperor, Qin Shi Huang, also wanted to live forever, like many other rulers before and after him. Unlike Gilgamesh, Qin Shi Huang did not embark on a journey to seek the herb of immortality. He instead issued a decree, reportedly giving an executive order to his government associates to search all of China for a potion that would grant him immortality. The quest did not leave out even the remotest of villages within his empire, new research reveals.

The findings, which were shared by Chinese news agencies at the end of December 2017, say that the emperor, famed for creating the world-renowned terracotta army, did indeed launch an obsessive quest to find the elixir of life. No potion managed to fulfill his quench to live forever, and he died at the age of 49, in 210 B.C. Some sources even claim that he might have used cinnabar, a deadly mercury sulfide, so instead of taking medicine to live longer, the emperor shortened his life before his time was up.

The compelling evidence of Qin Shi Huang’s mission was been found after Chinese researchers reviewed texts inscribed on wooden slips, approximately 2,200 years old. Over 36,000 examples of such slips (typically made of bamboo), containing some 200,000 characters of ancient Chinese, were found in 2002 in a deserted well in a village located in the central Chinese province of Hunan.

An important historical figure, Qin Shi Huang successfully managed to tame the six warring kingdoms of ancient China, unifying them in one single nation. After that, he declared himself as the emperor, and the latest readings of the wooden slips affirm the nature of his governance.

Besides fulfilling ambitions to strengthen his powers by introducing currency, or standardizing the systems of measures and weights in China, Huang was keen to use his position to find the secret of eternal life. As China’s Xinhua news agency reported, some of the wooden slips include “the emperor’s executive order for a nationwide search for the elixir of life and official replies from local governments.”

Response to his call arrived from even the furthermost places of the empire. “According to the calligraphic script on the narrow wooden slips, a village called ‘Luxiang’ reported that no miraculous potion had been found yet and implied that the search would continue,” reads the Xinhua agency news report. It continues: “Another place, ‘Langya,’ in today’s eastern Shandong Province near the sea, presented a herb collected from an auspicious local mountain.”

The findings are based on research carried out by Zhang Chunlong from the Hunan Institute of Archaeology. As part of the effort, the researchers examined 48 such wooden slips that were of a medicine-related nature, and dated from 222 B.C. to 208 B.C.

Chunlong also affirmed that the decree of the emperor reached almost every corner of the country, and as more commentaries go, such a quest was set to consolidate his powers even more. “It required a highly efficient administration and strong executive force to pass down a government decree in ancient times when transportation and communication facilities were undeveloped,” stated Zhang.

Earlier research revealed that there was an elaborate mailing service during the reign of Huang. Despite such achievements, he is not much of a favorite among historians, who traditionally paint him as an unmerciful tyrant and not without reason. The emperor commanded thousands of people into forced labor to work on his megalomaniac projects, such as his mausoleum and palace, or the famed Great Wall of China, later designated as one of the Seven Wonders of the Medieval World. In this context, urging an entire administration to find the elixir of life should not present itself as a surprise.

The wooden slips have filled other gaps in the knowledge of how the emperor governed, offering at the same time an insight into the early medical history of China. As it appears, the empire of Qin Shi Huang undoubtedly run a well-developed medicine administration and some of the treatments being offered to the sick are known to have been used for many years after the emperor’s death.

Unfortunately, doctors were able to take care of patients only if authorized by government officials. Details of any treatment by default also required excessive reporting in official papers. And, as you might easily guess, it was most common that only the people of the elite could access the care of doctors.

Concerning Qin Shi Huang’s quest for eternal life, maybe he did not find the elixir, but he took care to put in place some extra protection for the afterlife. Hence the 8,000 terracotta warriors representing his army of infantry, archers, horsemen, and chariot riders, all well arranged as guardians of his mausoleum.