As a photojournalist and war photographer, Robert Capa provided visual evidence of the wars that raged around the world in the first half of the 20th century. Risking his life, Capa covered World War II across Europe; on Omaha Beach, he was the only photographer who landed on D-Day. He also covered the Spanish Civil War from 1936 to 1939, the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, and in 1954, the First Indochina War.

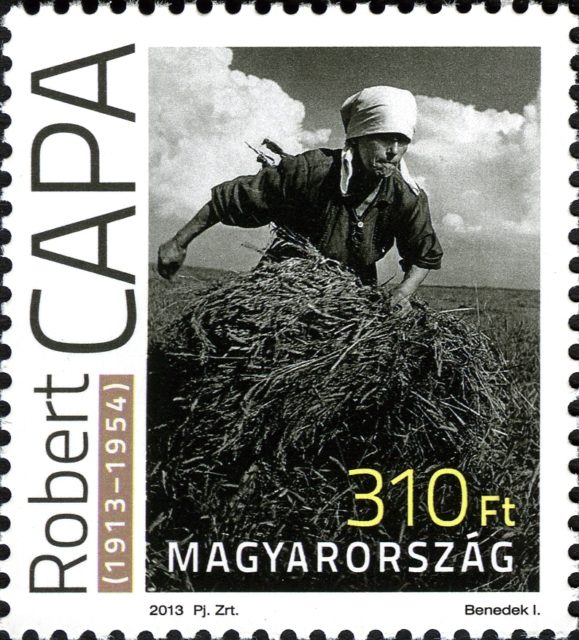

He was born in 1913 named Endre Friedmann into a Jewish family in Budapest, then part of Austro-Hungary. While barely 18 years old, Capa left Hungary due to accusations of Communist sympathies, and after settling in Vienna and later Prague, he finally moved to Berlin. In the new city, he started studying journalism at Berlin University. To support himself, he took a part-time job as a darkroom assistant and later found employment as a staff photographer at Dephot, the German photographic agency.

Although he initially wanted to become a journalist, working as a photographer made him see he must switch paths. In 1932, he captured his first published photo of Leon Trotsky while the exiled Communist revolutionary was making a speech in Copenhagen. His career as a photographer was just starting to blossom when he was caught up in the rise of the Nazi Party, which instituted restrictions on Jews, prohibiting them from attending universities and colleges.

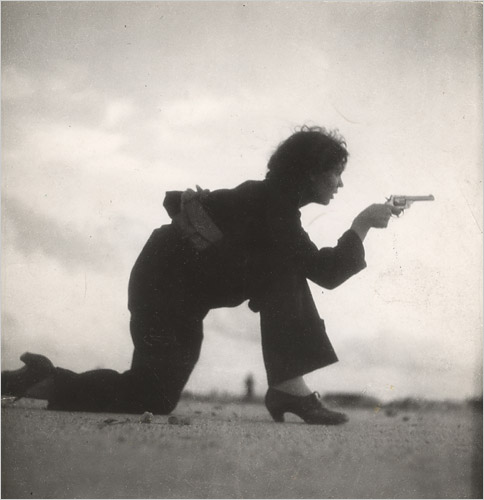

In 1934, Capa moved to Paris, where he changed his birth name to avoid religious discrimination, something that was common in France at that time. The same year, he met Gerda Pohorylle, also a photographer who had fled Germany for the same reasons. She adopted the name of Gerda Taro, under which she became famous in her own right. The couple lived together in Paris, and in 1936, they both traveled to Spain with the intention of documenting the civil war there.

In 1937, while Capa was on a brief trip to Paris, Gerda was working in Madrid, covering the Battle of Brunete. As she was returning from the assignment, her car was crushed by an out-of-control tank and Gerda was killed. Capa was deeply traumatized by her death. He never married.

During the Spanish Civil War, Capa took one of his most famous photographs, “The Falling Soldier,” in which he captured the death of a Republican soldier. The photo was at first published in French magazines, but soon it reached Life magazine and the British photojournalism magazine Picture Post, which regarded the 25-year-old author as “the greatest war photographer in the world.”

While in Spain, Capa befriended Ernest Hemingway and accompanied him, photographing the war as they went, which the writer later described in his 1940 novel For Whom the Bell Tolls. Hemingway’s article about his time in Spain was published in Life magazine, along with many photos taken by Capa.

In 2007, three boxes with film rolls that contained 4,500 35mm negatives of the civil war, taken by Capa, Chim (David Seymour), and Taro and which had been considered lost since 1939, were discovered in Mexico. A movie about those photographs, The Mexican Suitcase, directed by Trisha Ziff, was made in 2011.

In 1938, Capa traveled to the city of Hankou, in China, where he documented the resistance to the Japanese invasion, and the photos were also published in Life. The following year, again escaping Nazi persecution, Capa left Paris and moved to New York City to search for work. He was working for Collier’s Weekly when World War II was declared, but he was fired soon after and started shooting regularly for Life. He traveled to various European destinations, taking photos of the war, and was known as the only “enemy alien” photographer for the Allies.

In July and August 1943, Capa was with American troops in Sicily, in the village of Sperlinga, which was heavily defended by the Nazis. The photographer captured the sufferings of the people during the bombing and their happiness at the arrival of the American soldiers. He shot one of the most world-famous photos in the village, of a Sicilian peasant indicating the direction of the German troops. On the 7th of October, 1943, while he was accompanying the Life reporter Will Lang Jr. in Naples, Capa captured photos of the Naples post-office bombing.

On D-Day, Capa landed on Omaha Beach alongside the American troops, where they confronted one of the heaviest resistances from the German forces. Capa took 106 pictures while under constant fire. Almost all of his photos–11 survived–were destroyed in an accident in a photo lab in London. That surviving group, again published in Life magazine, in June 1944, became known as “The Magnificent Eleven,” and are considered the most significant photos taken by Capa.

In 1943 he became romantically involved with Elaine Justin, who was still married to the actor John Justin at the time. Their relationship lasted until 1945, when Elaine left Capa and married Chuck Romine. After a few months, Capa became Ingrid Bergman’s lover and followed her to Hollywood, where for a brief spell he worked for American International Pictures. However, the relationship ended the next summer when Capa went to Turkey.

On the April 18, 1945, Capa took another photo that became known as one of the world’s most famous. He was in Leipzig, Germany, and photographed a fight for a bridge. One of these photos captured the death of the American infantryman Raymond J. Bowman by sniper fire and was published in Life with the title “The picture of the last man to die.”

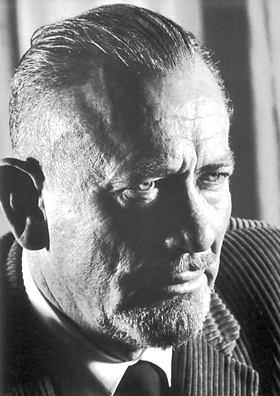

Before the invasion of Italy in 1943, Capa shared a room in a hotel in Algiers with the American writer John Steinbeck, and the two became close friends, reconnecting later in New York. In 1947 they traveled together to the Soviet Union, where Capa was photographing a nation torn by war, and Steinbeck was working on his book A Russian Journal. Capa took photos in Moscow, Tbilisi, Kiev, Batumi, and also among the ruins of Stalingrad. Their friendship lasted until Capa’s death, which Steinbeck took very hard.

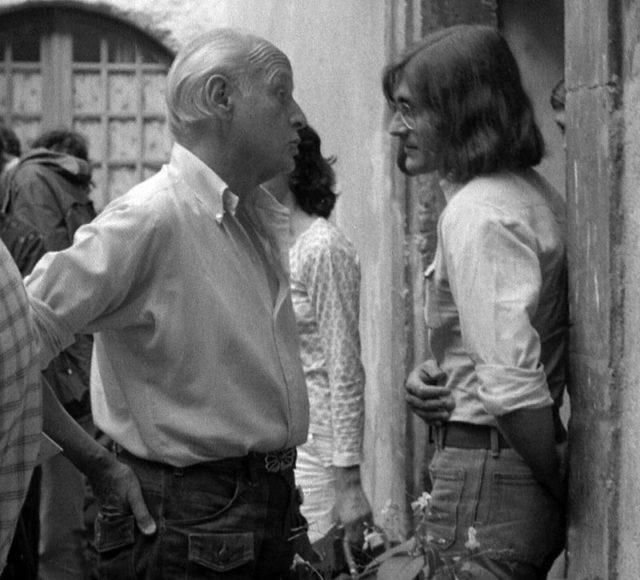

While he was living in Paris, Capa had shared a darkroom with the French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson. In 1947, the two established Magnum Photos, the first photographic cooperative agency, to manage the work for and by freelance photographers. Other members of Magnum Photos included David Seymour, William Vandivert, and George Rodger. That same year, Capa was awarded the Medal of Freedom by President Dwight D. Eisenhower, for recording World War II in photographs.

Henri Cartier-Bresson (left) and a young intern at the Rencontres internationales de la photographie in Arles 1974. Author: Rolph31000. CC BY-SA 4.0

In 1948, Capa traveled to Israel and documented the people and places there during the formation of the country and while it was being constantly attacked by neighboring states. His photos accompanied Report on Israel, a book by Irwin Shaw, another friend of Capa’s.

In 1952, Capa became the president of Magnum Photos. The next year, along with Truman Capote and John Huston, he went to Italy, where he photographed the making of the film Beat the Devil. In their free time, the photographer, the screenwriter, the director, and the actor Humphrey Bogart enjoyed playing poker.

After he had finished his work in Italy, the president of Magnum Photos went to Japan for an exhibition associated with the cooperative. During his stay there he got a proposition from Life magazine to take an assignment in Southeast Asia, to record the ongoing war there, the First Indochina War in which the French had been fighting for eight years. Even though, only a few years back, Capa had said that he was done with war, he took the assignment and joined the French forces, along with Jim Lucas and John Macklin, journalists from Life and Time.

The group was traveling through a dangerous area that was constantly under fire when Capa decided to leave the vehicle to record the advance. Soon after leaving the jeep, he stepped on a mine and died. He was 40 years old.

Robert Capa coined the term Generation X which he used as a title for his photo essay dedicated to the young people who were reaching adulthood right after World War II. Regarding his essay, Capa said, “We named this unknown generation, The Generation X, and even in our first enthusiasm we realized that we had something far bigger than our talents and pockets could cope with.”

His approach to work redefined wartime photojournalism.