Once upon a time, there were four little Rabbits, and their names were Flopsy, Mopsy, Cottontail, and Peter.

So wrote Beatrix Potter all those years ago, unaware that such a sentence would reveal a whole imaginary world to children around the world who, even today, after more than a century, crave to hear “just one more” story of Peter Rabbit and his pals before bedtime.

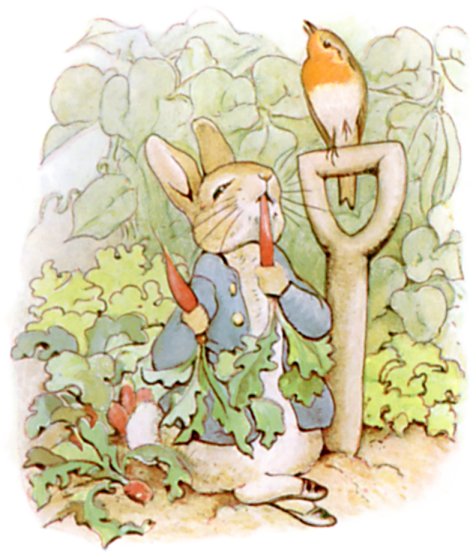

The delightful stories by this revered author, who was also a passionate illustrator and produced all the images for her books, have become classics of children’s literature.

One may not know about Peter Rabbit’s adventures, but there’s hardly anyone who isn’t familiarized with the soft, aquarellic images of gardens and animals dressed in pastel outfits with incredibly human-like expressions on their faces.

Known as Beatrix, Helen Beatrix Potter was born in 1866 into a privileged family in Kensington, London. She spent her early years isolated from other children as she was educated by a governess. This, in fact, might have been the initial impetus for creating a much-loved imaginative world of fauna and flora that Beatrix could escape to during the holidays with her family in Scotland and the Lake District.

Deeply inspired by her surroundings, she loved to spend hours observing and painting her numerous pets, such as rabbits, mice, frogs and lizards and the landscape around them. Beatrix was a dedicated and an industrious student who diligently followed the instructions of Miss Cameron, her art teacher.

Not surprisingly, her first artist models were her pet rabbits. The first one was Benjamin Bouncer, a lover of crispy, buttered toast, while his successor was named Peter Piper–the untiring companion of Beatrix during her walks. Every year, Beatrix looked forward to the summer because of her family’s holiday itinerary, which included three months in northern Scotland, and to her and her brother this meant only one thing: freedom. To run through the green fields, climb the trees, enjoy the endless flowery meadows, and, most of all, spend hours observing plants and insects in the countryside. One of those summers marked the beginning of Beatrix’s love of the Lake District when her family decided to stay at a place near Lake Windermere.

Long before she became a popular published author, Beatrix developed a particular talent for scientific illustration by drawing and exploring fungi. In 1896, she wrote a paper on fungi reproduction titled “On the Germination of the Spores of Agaricaceae,” which, unfortunately, was rejected by the Royal Botanical Gardens. A year later, George Masse, a fungi expert from Kew gardens in London, presented her work to the Linnean Society of London, a place where Beatrix, being a woman, was not permitted to present it herself. Nevertheless, scientists today recognize and appreciate her contribution to mycology.

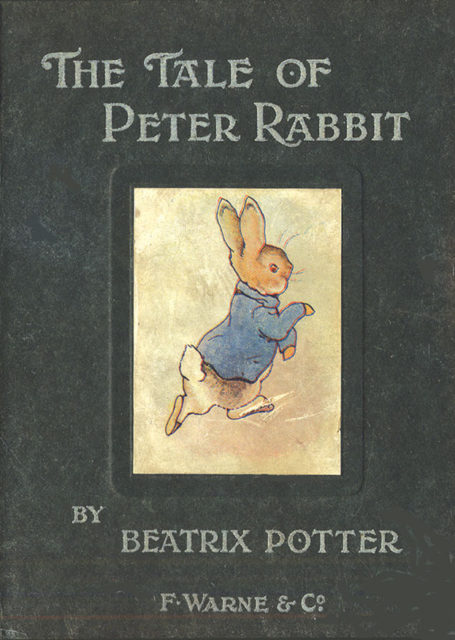

The male members of the scientific milieu in England were not the only ones who ignored Beatrix’s aspirations. Her family also disapproved, believing that a proper, respectable lady must eventually marry and certainly mustn’t work. However, Beatrix’s desire for sharing her imaginative art prevailed, and after a few publications of greeting-card designs and illustrations, her stories were about to see the light of day. Several publishers rejected The Tale of Peter Rabbit, so the persistent Beatrix decided to publish it by herself.

In December 1901, Beatrix printed 250 copies and handed them to her family and friends. The book was immediately praised and quickly gained a reputation, so the publishing house Frederick Warne & Co. reconsidered their decline and offered a contract to Beatrix. In October 1902, the story of Peter Rabbit became a bestseller and was followed by two other well known books, The Tailor of Gloucester and The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin. The publication of Beatrix’s legendary stories had begun.

At the publishing house, Beatrix encountered Norman Warne, her official editor, who soon recognized his affection towards her–and she ardently replied. Norman’s proposal, however, was opposed by the Potters, and they refused to allow their daughter to marry someone who worked “in a trade.” However, as always, Beatrix listened to her heart and became engaged to Norman in 1905. Tragically, Norman died of leukemia a month after their engagement.

Following Norman’s death, Beatrix found solace in her most beloved place, the Lake District. She invested in a farm known as Hill Top Farm, a place that would appear in a number of her stories. The negotiations over her investments were conducted by William Heelis, a local solicitor with whom Beatrix became very close.

In 1912, Beatrix accepted William’s marriage proposal and married him the following year. The couple lived at Castle Cottage in the Lake District, where Beatrix spent the last of her days before she died in 1943.

The Tale of Peter Rabbit, which Beatrix self-published initially, has reached 45 million copies sold around the world.