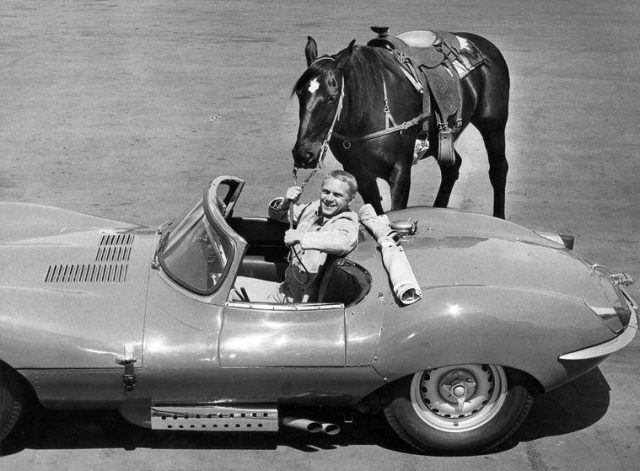

Ever since his death in 1980 at the age of 50, Steve McQueen’s reputation as the King of Cool has grown and grown. Black-and-white photos of McQueen’s lean, weather-beaten face squinting into the sun compete with vivid color images of him straddling a motorcycle or climbing out of a race car, his eyes startling blue.

Then there are the photos of McQueen with his arm around his second wife, Ali Macgraw, the patrician brunette beauty fresh off Love Story who he stole from her Hollywood husband, Robert Evans, while she was his co-star in The Getaway.

An essential aspect of a cool persona is a temperament that is laid-back and confident. In the photos, it’s as if McQueen were saying, “I don’t have to work to get these acting parts or awards or million-dollar fees, or these race cars, or even these beautiful women, they just come to me without effort.”

But what is being lost in the iconography of Steven McQueen is how badly he wanted certain things, none more so than a film career in the late 1950s. There wasn’t much of anything he wouldn’t do to get it. The Magnificent Seven, released in 1960, is the story of McQueen’s reality. The King of Cool did more than break a sweat to get cast in and film this movie–he had a series of meltdowns.

Directed by John Sturges, The Magnificent Seven is one of the most popular and enduring of all Westerns. Seen today, it’s not a bit dated, creating excitement all the way through, and true drama. It’s seen as the bridge between the more straightforward Westerns like The Searchers and the late 1960s Spaghetti Westerns like The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Based on the Akira Kurosawa film The Seven Samurai and powered by an Elmer Bernstein score, it is a classic.

Yet while it was being developed and filmed, The Magnificent Seven was a frantic, troubled, uncertain project. There was fighting over who owned the initial rights to adapt it and over screenwriter credit afterward. It was cast in a hurry as an Actors Strike loomed, and shot in Mexico while a disapproving Mexican censor rammed through changes. Just as Casablanca was a chaotic set of last-minute script changes and lead actors who didn’t connect offscreen and yet is now one of the most beloved films of all time, the much-admired Magnificent Seven was an angry set and no one contributed to the tense atmosphere more than Steve McQueen.

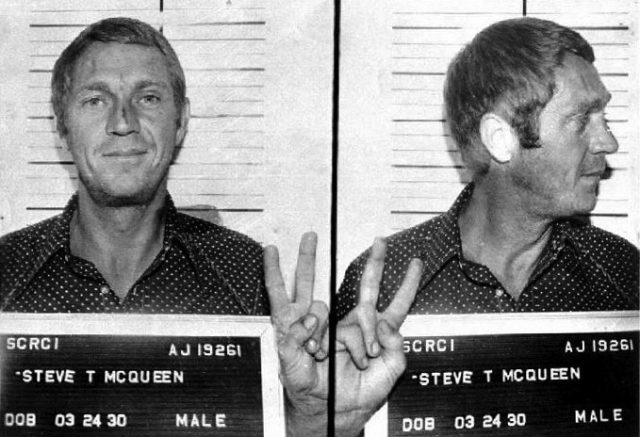

In the late 1950s, McQueen was primarily a TV actor and he was pushing 30. America liked him as bounty hunter Josh Randall in the TV Western Wanted: Dead or Alive. He had won a few film parts, but they were in sci-fi films like The Blob or the soapy Never Love a Stranger. When McQueen heard they were casting The Magnificent Seven, he immediately wanted to be one of the Seven, and told his agent to get him out of his TV contract for long enough to do the picture. But the producers of Dead or Alive, a hit series, said no. McQueen personally pushed for it and lobbied, and they still said no.

So McQueen intentionally got himself into a car accident.

The story has circulated in Hollywood for a while that McQueen risked injuring himself or even killing himself to get a part in The Magnificent Seven, and some people assume it’s exaggerated. But his first wife, Neile, has confirmed that while they were on vacation in Boston, McQueen deliberately ran his car into the side of a bank. His agent said, “He took his rented Cadillac and ran it into the Bank of Boston and came out of it with whiplash.”

McQueen returned to Los Angeles with his neck in a stiff brace. He got out of his TV contract and he won the part of the drifter gunman Vin Tanner in The Magnificent Seven.

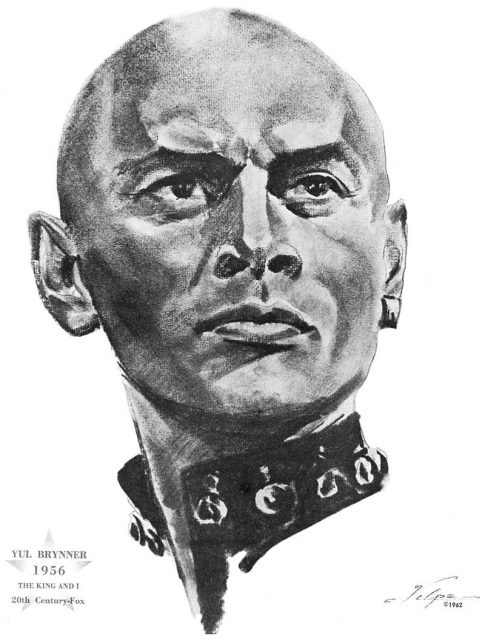

However, when he reported to the set, Steve McQueen wasn’t scamming TV producers any longer, he was coming up against an actor who was definitely his match in ambition: Yul Brynner, the star of The Magnificent Seven. Brynner, who had say in the casting, supported hiring McQueen and may even have suggested him. That made no difference. Stories of the enmity between the hyper-competitive McQueen and Brynner would soon become so widespread that Brynner was forced to give a newspaper interview to calm things down.

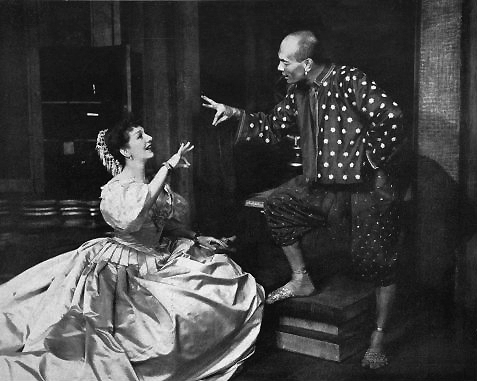

Brynner, 39, had a huge advantage. He’d had a red-hot run in major movies in the previous two years, from his Academy Award-winning part in The King and I to The Ten Commandments to Anastasia. Women found him incredibly sexy. Eli Wallach, who portrayed the villain in The Magnificent Seven, said, “He had a magnetism.”

It may seem that quintessential American actor Steve McQueen could have nothing in common with European exotic Yul Brynner. But the two men had similar backgrounds, albeit on different parts of the planet. McQueen’s father abandoned his mother at their child’s birth, and, an alcoholic, she put Steve into a boy’s home. He never graduated from high school; dyslexic, he lived on the streets, running with gangs for a while before joining the Marines. As for Yul Brynner, he encouraged reporters to think he was a gypsy or half-Japanese, half-French, or an orphaned Mongolian noble. In fact, he was none of those things, born in a corner of Russia close to China called Vladivostok. His father, a mining engineer, also abandoned his family to financial peril when Yul was young. He had little formal education and ended up as a circus acrobat in Paris. “He spoke of his father with bitterness,” Yul’s daughter said in a documentary. McQueen and Brynner were both married multiple times, better fathers than they were husbands.

Yul loved Kurosawa’s The Seven Samurai when he saw it in the theater and insisted in later interviews he personally obtained the rights to film the story in America from the Japanese. This was simply not true. Producer Walter Mirisch negotiated the American rights, with Anthony Quinn set to star. After Brynner took over, Mirisch was out and so was Quinn.

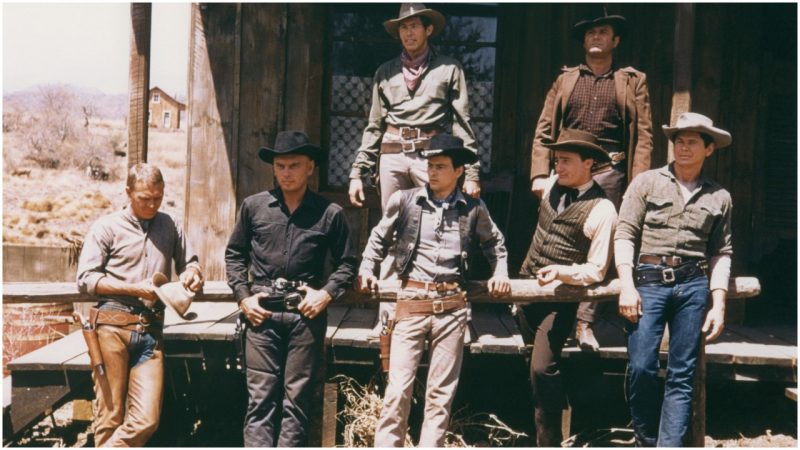

The fact that there were seven gunmen in the film meant it had the potential to get crowded. Sturges cast the parts alongside Brynner with what were later called “the young bucks”: McQueen, Charles Bronson, Robert Vaughn and James Coburn, as well as Brad Dexter and Horst Buchholz. Right off the bat, McQueen wasn’t happy with the number of lines he had in the film. He griped to Vaughn and the other young bucks that Brynner had far and away the best lines. He had a separate massive trailer and a luxury limousine. Plus, onscreen Brynner had the biggest horse and the biggest gun. They were going to suffer in comparison, McQueen kept saying.

Once filming was underway, McQueen decided to do what he could to take the picture away from Brynner. Since the two characters, Chris and Vin, were, ironically, close friends onscreen, they were in a lot of shots together. McQueen constantly did what he could to distract attention so future audiences would look only at him: he took off his hat, played with his gun, checked his bullets, twisted in the saddle, any bit of business possible. When the camera was rolling and he was crossing a stream on horseback behind Brynner, he swung out of his saddle, scooped water in his cowboy hat, and doused himself.

Another story, one that is sometimes discounted, revolves around certain mounds of dirt. When Brynner had to stand next to McQueen, he reportedly saw to it that there was a small hill of dirt to stand on so he was taller. (Brynner was five foot eight and McQueen was five foot ten.) McQueen, whenever possible, kicked the dirt hill down. According to Eli Wallach, Brynner was so concerned about McQueen stealing scenes that he hired an assistant to count the number of times McQueen touched his cowboy hat while Brynner was speaking.

In McQueen’s words, “We didn’t get along. Brynner came up to me one day in front of a lot of people and grabbed me by the shoulder. He was mad about something. I don’t know what. He doesn’t ride well and knows nothing about guns so maybe he thought I represented a threat. I was in my element. He wasn’t. Anyway, I don’t like people pawing at me. I said, ‘Take your hands off me.’ When you work in a scene with Yul, you’re supposed to stand perfectly still ten feet away. Well, I don’t work that way. So, I protected myself.”

The Magnificent Seven opened in October 1960 but was not a hit at first. After becoming a sensation in Europe, the movie was re-released in the United States and started to gain a following. All of the actors acquit themselves well, with Brynner the soulful leader, his eyes burning into the camera, and McQueen showing likability and great athletic skill, including hurling himself over a wooden counter head first when under fire.

Following The Magnificent Seven, McQueen’s anti-hero vibe was perfect for the 1960s. After starring in The Great Escape, Bullitt, The Getaway, and Papillon, he became the highest-paid actor in America. He was a difficult actor to direct and to star with in many of those movies, however. He was particularly envious of Paul Newman’s career, and in The Towering Inferno he insisted the two men have the exact same number of lines, that McQueen’s fire chief character doesn’t appear until more than 40 minutes into the film, and the fire chief be the hero. The two men were so competitive overbilling on the film poster that the desperate studio had to come up with a “diagonal” solution.

No longer at the top of the A-list was Yul Brynner. He appeared in more than 20 movies after The Magnificent Seven, but his career had peaked. His style of acting didn’t fare as well as McQueen’s or Newman’s in the 1960s and 1970s. But in the 1970s, Brynner received a phone call from a surprising source: Steve McQueen. He wanted to apologize for his actions in The Magnificent Seven.

Brynner accepted the apology with grace and humor. He said, “I am the king and you are the rebel prince. Both are dangerous.”