We often say that economic bubbles are irrational, but it seems that, in some way, we must like the irrationality that surrounds this rather strange free-market phenomenon since we keep repeating the same mistakes over and over again.

Apart from irrationality, the other driving forces behind the economic bubbles, financial panics, and crashes of the economy are, without a doubt, human greed and fear. Sadly enough, these two emotional states managed to remain constant throughout the centuries and have shaped the global economic processes, often causing catastrophe.

As mentioned, major speculative bubbles are nothing new in the free-market economy, and if we dig a little deeper in the economic history books, we come to the conclusion that they’ve been around since at least the 17th century, when the most famous example of all speculative bubbles, the Dutch “Tulip Mania” bubble, aka Tulipomania, came into being.

Tulips traveled a long way before they became a national symbol of the Netherlands. While most people think that the flower is native to the Netherlands, the fact is that tulips were first imported there from the Ottoman Empire in the 1590s. According to legend, the man who takes credit for the popularization of tulips was a Dutch ambassador at the Ottoman Empire. He noticed the flower for the first time at the court of Suleiman the Magnificent and was so affected by its beauty that he decided to send several examples to his botanist friend in the Nederlands. It didn’t take long before tulips became a massive novelty in the country and went on to become a major status symbol of the era. However, it took several more decades before the Dutch “Tulip Mania” bubble burst.

Unlike any other flower that could be found on the Old Continent during the first decades of the 17th century, the colorful tulips quickly became extremely popular and the Dutch went completely crazy for it. “Neighbors seemed to talk to neighbors; colleagues with colleagues; shopkeepers, booksellers, bakers, and doctors with their clients gives one the sense of a community gripped, for a time, by this new fascination and enthralled by a sudden vision of its profitability,” wrote Anne Goldgar in Tulipmania: Money, Honor, and Knowledge in the Dutch Golden Age.

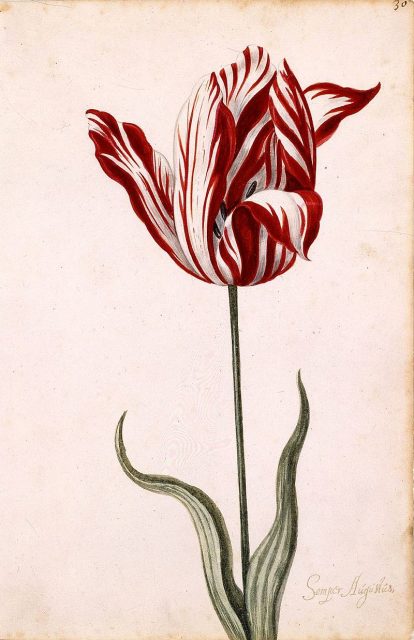

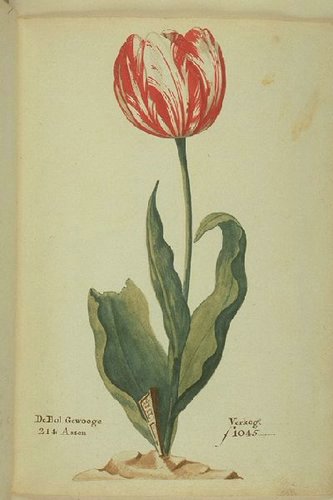

For some rare tulips with distinctive patterns, merchants would pay incredibly high prices, which led to sharp increases in the prices of the flower bulbs. According to The Economist, Semper Augustus, a rare type of tulip, was valued at 1,000 guilders in the 1620s and, several months before the bubble burst in the 1630s, had increased in price to 5,500 guilders for a single bulb, which was the cost of a luxurious house in Amsterdam. The enormous price rise of the tulip bulbs didn’t end there. As months passed by, more and more speculators piled into the market, with some of them making unimaginable profits, which eventually led many others to get involved in the trade.

According to the BBC, the prices doubled by the first month of 1637, when a single bulb of Semper Augustus was valued at 10,000 guilders. “It was enough to feed, clothe and house a whole Dutch family for half a lifetime, or sufficient to purchase one of the grandest homes on the most fashionable canal in Amsterdam for cash, complete with a coach house and an 80-ft garden–and this at a time when homes in that city were as expensive as property anywhere in the world,” wrote Mike Dash, the author of Tulipomania: The Story of the World’s Most Coveted Flower and the Extraordinary Passions It Aroused.

Literature is full of anecdotes of the era, such as the one about the sailor who ended up behind bars after he mistakenly ate a tulip bulb thinking that it was an onion. The “onion” he ate was, in fact, a rare Semper Augustus tulip bulb that according to most accounts, if sold, could have provided just enough money to feed an entire ship’s crew for 12 months.

Beyond everyone’s expectations, the prices continued growing, and then, all of a sudden, as usually happens with almost every speculative bubble in history, Tulip Mania reached its peak and the market for tulips collapsed. Tulip buyers were nowhere to be found. Within a few days, tulip prices fell as low as a hundredth of their previous value, which led to a financial catastrophe and panic throughout the country.

There is still a debate concerning the consequences of what is universally known as the first recorded financial bubble, but according to most accounts, Tulip Mania resulted in a depression that lasted several years. However, the trauma left such a lasting impression that, even decades after Tulip Mania, people remained reserved when it came to speculative investments.