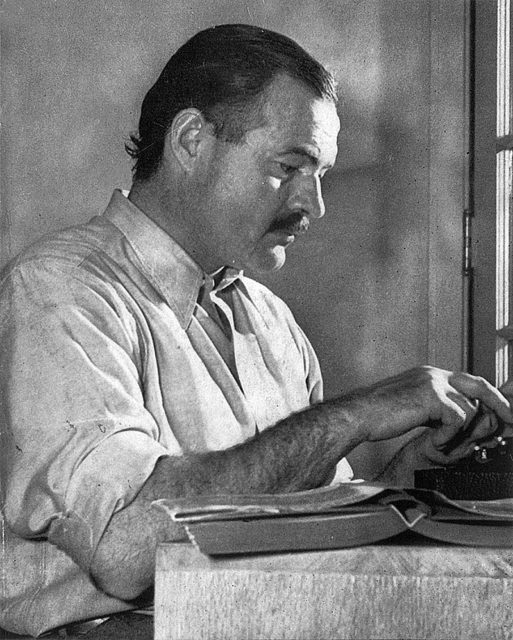

The legends surrounding Ernest Hemingway can be as interesting as the plots of his novels. The author was famous for his personal life, but some of “Papa’s” adventures verge into apocrypha.

“For sale, Baby shoes, Never Worn.”

It’s a story so short that it could fit into a title yet it resonates with depth and tragedy. This particular quote, supposedly originating in the 1920s, served as confirmation of Hemingway’s extraordinary talent and wit. It has also influenced numerous attempts to create a story in the six words frame, so-called flash or sudden fiction, giving only a glimpse of a story but in that glimpse delivering so much more.

This particular story was believed to be written on a napkin in Luchow’s restaurant in Manhattan, while another version of the story claims that it was composed in the Algonquin Hotel, where a circle of New York intellectuals (known as the Algonquin Round Table) enjoyed discussions–and drinking–during lunch time. This is only the first of the discrepancies that surround this legend, for no one can say with certainty where it happened, or when, and witnesses are elusive.

Allegedly, the story was a result of a $10 bet among Hemingway and several writers at a lunch spiced with wordplay. Hemingway asked each of his colleagues to place a $10 wager, and in return, he would match it. His task was to create this shortest of stories.

The only problem is, Hemingway probably never wrote it.

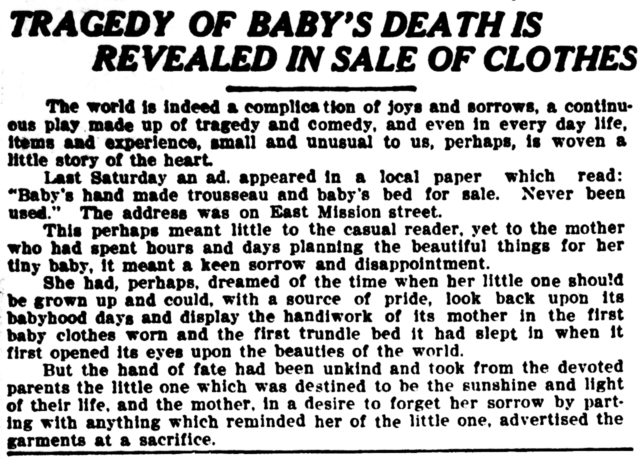

Or if he did, the story wasn’t entirely his invention. Similar “ads” have been recorded as early as 1906. According to the Quote Investigator, an earlier version of this minimal sentence was “For Sale, Baby Carriage, Never Used,” published in a newspaper section called Terse Tales of the Town.

Whether this was a bad joke or someone’s sad memory, we will never know.

There are also two other versions written years before the supposed Hemingway bet was placed. One of them was an essay by William R. Kane, about a certain “wife who has lost her baby.” It was published in 1917, by the title “Little Shoes, Never Worn.”

The “carriage” version was repeated in 1921, appearing in a column written by Roy K. Moulton, which held an ad attributed to an anonymous real-life character simply called Jerry:

There was an ad in the Brooklyn “Home Talk” which read, “Baby carriage for sale, never used.” Would that make a wonderful plot for the movies?

Let’s just assume that Ernest Hemingway was aware of these earlier versions and decided to cheat his way into winning a bet. After all, he very well acquainted with the world of reporters, journalists, and feuilleton writers. He could have known about the six-word punchline long before and could have used his wit to collect the wager and establish himself winner among potential rivals.

But, truth be told, there is no evidence that such a bet actually ever took place, nor that Hemingway ever used this intelligent quote to soften the hearts of sardonic writers.

The story can be traced to a book published in 1991, titled Get Published! Get Produced! A Literary Agent’s Tips on How to Sell Your Writing. The book was written by a literary agent, Peter Miller, who mentions the anecdote about the bet placed in Luchow’s, as he heard it from an older newspaper account:

Apparently, Ernest Hemingway was lunching at Luchow’s with a number of writers and claimed that he could write a short story that was only six words long. Of course, the other writers balked. Hemingway told each of them to put ten dollars in the middle of the table; if he was wrong, he said, he’d match it. If he was right, he would keep the entire pot. He quickly wrote six words down on a napkin and passed it around; Papa won the bet. The words were “FOR SALE, BABY SHOES, NEVER WORN.” A beginning, a middle and an end!

There have been several more accounts over the years that attributed the quote to Hemingway, including an article by Arthur C. Clarke in a 1998 Reader’s Digest essay. Miller mentioned it again in a 2006 book, cementing it as Hemingway’s brainchild.

It was not until 2012 that a true academic investigation took place in order to solve the mystery of the never worn shoes. The Journal of Popular Culture published an article written by Frederick A. Wright that examined the origins of this story and debunked it as false.

Many were probably disappointed to hear that the Nobel Prize-winning author wasn’t the man behind the heart-breaking story that he allegedly claimed was his best work. Nevertheless, the truth reveals something else―this false authorship only helped the story reach and inspire numerous people. These six words found their way into readers’ lives, and in the end, it doesn’t matter who wrote them. What matters is the impact it left on the way we perceive literature, as a compression of feelings that communicate directly with the human soul.