Before the world was struck with Beatlemania–much, much before, for that matter―a different kind of craze swept through Europe, one that would reveal ties to demonic forces, religious cults, and hallucinogenic drugs.

The Dancing Mania was a strange social phenomenon that escapes clear explanation to this day. It was recorded throughout the history of the Middle Ages, with earliest accounts dating from the 7th century.

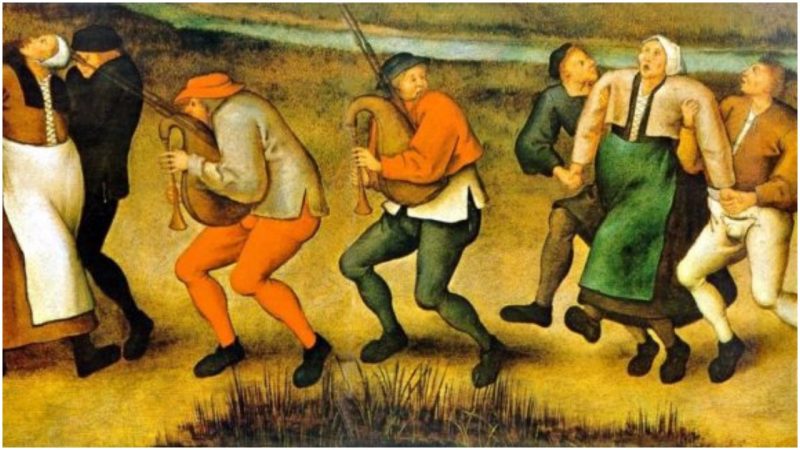

The symptoms varied, but there was one constant―those “infected” would move in groups, performing something similar to dancing as their bodies twitched with spasms, leaving an observer with a sense of dread. People who engaged in this activity didn’t seem to be aware of themselves. As if in some sort of trance, sometimes the dancing mania would possess a person for days, weeks, and in some cases months. This was no joking matter, as the people afflicted by this peculiar obsession would sometimes die of exhaustion or hunger.

In 1237, in Erfurt, Germany, a group of children showed signs of the dancing mania, as they traveled the 13 miles to the nearby town of Arnstadt, dancing and jumping throughout their journey. Once they reached their destination, they fell to the ground, as a result of exhaustion.

A chronicle that perhaps dates from the time of the event claims that most of the children died soon afterward, and the ones who survived fell into a state of permanent mental illness accompanied by tremors.

It’s likely that it was this or a similar story from which the legend of the Pied Piper of Hamelin sprung―a folk tale about a piper with supernatural powers who leads a group of children to their death, as an act of revenge against the townsmen who refused to pay him for his services of eradicating rats in times of plague.

A native of Erfurt, Justus Friedrich Karl Hecker, wrote a book published in 1888, titled The Black Death and the Dancing Mania, in which he collected numerous accounts of Dancing Mania, relating it to the horrific consequences of the Bubonic plague that reached its peak in Europe in the mid-14th century.

In the book, Hecker, a doctor of medicine, describes the dancing frenzy as a reaction to the years of Black Death, as the plague epidemic was dubbed. He believed that the hardships brought by the disease indirectly manifested themselves in the form of a collective madness. It is certainly true that the pandemic, which wiped out one-third of the world’s population, left a devastating effect on the human psyche.

One the largest outbreaks of the mysterious dancing “sickness” happened in Aachen, Germany, in 1374. Several thousand frenzied people danced in fits that lasted for weeks.

Hecker’s description of this strange gathering invokes rather hellish visions, resembling the miniatures of Hieronymus Bosch:

They formed circles hand in hand, and appears to have lost all control over their senses, continued dancing, regardless of the bystanders, for hours together, in wild delirium, until at length they fell to the ground in a state of exhaustion. They then complained of extreme oppression and groaned as if in the agonies of death, until they were swathed in cloths bound tightly around their waists, upon which they again recovered, and remained free from complaint until the next attack.

The Church was suspicious of these events right from the start. The theological explanation fell into three categories: people affected by the dancing plague were either under the control of the devil, or they were cursed by a saint, most probably St. John or St. Vitus. The third explanation was that this was nothing but a band of heretics, who through the guise of madness found a loophole to practice their unholy rituals without being disturbed.

Apart from claims that all these events were staged, the use of hallucinogens was also considered a potential explanation, by both the church and contemporary authorities. The names St. Vitus’ Dance, or St. John’s Dance, were soon accepted, and the people begged the ancient saints for forgiveness.

From Aachen, the mania was reported to spread to Utrecht in the Netherlands and Liège in Belgium. Around that time, a report from Metz in France claimed that 11,000 people had succumbed to the Dancing Mania. The rich trading city was turned into a bizarre gathering of the insane. The death toll was rising, as the “dancers” fell like flies after a while of non-stop jumping and dancing.

In order to soothe their sufferings, music was played, and in order to keep them off the streets, huge guild halls were adapted to fit a large number of people. The “sick” would then be herded into these structures, together with musicians, as if the entire spectacle resembled a modern musical concert.

After the outbreak in Aachen, the next documented case in which a large group of people was involved occurred in Strasbourg, France, in 1518.

Allegedly, a woman started the dance and within a month, more than 400 people were “possessed.” Historian John Waller, who is the author of the book A Time to Dance, A Time to Die: The Extraordinary Story of the Dancing Plague of 1518, studied the archives and concluded that the event indeed happened, as he confirmed it from various different sources:

These people were not just trembling, shaking or convulsing; although they were entranced, their arms and legs were moving as if they were purposefully dancing.

Many died of strokes and heart attacks, after pushing their bodies to extreme limits of endurance. During the course of history, experts have tried to produce a medical explanation on this subject but all have failed to properly explain the causes of this hysteria.

One of the most prominent theories claims that the main reason behind this mass mania was poisoning by Claviceps purpurea, a fungus known to infect rye and other cereals, a condition called ergotism. Symptoms of ergot poisoning include hallucinations, convulsions, delirium, psychosis, a painful burning sensation in the limbs and extremities, headache, and it can cause damage to the central nervous system.

Others propose that the symptoms were similar to encephalitis, epilepsy, and typhus, but none of these explanations could answer for all the symptoms exhibited in the reports.

In Italy, a similar social phenomena called the tarantella was attributed to spider bites. The poison produced by spiders or scorpions was considered to cause such madness, but this scenario is hardly possible in such mass cases.

Even though sources are scarce and unreliable, everyone agrees that the phenomena was no fiction. It indeed happened and it was the earliest-recorded case of a psychic epidemic that shook the world of medieval Europe just as the plague was retreating, leaving a trail of more than 350 million dead worldwide.